Pages

▼

Monday, 16 August 2010

Witches (1) A word about witches

This is going to be the first in a couple of posts about witches. In the next one I’m going to be talking specifically about witches in children’s fiction, but first some thoughts about witches in general.

The earliest witch I can think of is the Witch of Endor in the Bible. Though she’s never actually called a witch, the inference appears to be that if she has a familiar spirit and can communicate with dead, that’s what she must be. Nowadays she might be called a medium. (The column-header gloss of my 1810 Bible says quite definitely: ‘Saul confulteth a witch’) In spite of having ‘banished from the land all who trafficked with ghosts and spirits,' King Saul visits her secretly, in disguise and asks her to call up the spirit of Samuel. “Tell me my fortunes by consulting the dead,” he demands. The woman reluctantly obliges. It’s not clear from the Bible account that Saul ever sees Samuel at all: the woman does, and describes him: “An old man cometh up, and he is covered with a mantle.” Of course it ends in disaster for Saul, since the displeased Samuel prophesies his death. (1 Samuel 28).

It’s a complex story which may be read as critical of Saul’s hypocrisy in first banning consultations with the dead and then employing them himself. On the other hand, Saul is desperate. “I am in great trouble; the Philistines are pressing me and God has turned away; he no longer answers me through prophets or through dreams, and I have summoned you to tell me what I should do.” This is a clearly a story from a time of great religious conflict when the monotheistic worship of Jehovah was battling it out against the polytheistic religions of the area. Samuel tells Saul that one reason the Lord “has torn the kingdom from your hand and given it… to David”, is that Saul has “not obeyed the Lord, or executed his judgement against the Amalekites”. (Read: not massacred them.) It’s a tough row to hoe, being king of Israel. But I don’t find the Bible account especially critical of the woman. Saul puts her in an awkward spot and she does what she’s asked, that’s all.

So why, in popular culture, are witches nearly always women? Or to put it another way round, why has women’s wisdom over the past few millennia so often been distrusted as likely to be ungodly in origin – and therefore evil? In one sense it’s obvious. Polytheisms are usually tolerant of rival beliefs, not seeing them as rivals. A monotheistic religion, if it is to remain monotheistic, cannot tolerate diversity of opinion. This is also why so many monotheistic religions devolve into schisms and splinter groups, and persecute one another. The Christian martyrs suffered because of a head-on collision between a system that asked for recognition of all other gods, including the reigning Emperor, and a system that demanded recognition of none but One.

Monotheisms must control their adherents by strict codes of belief and behaviour. (Saul ought to have destroyed those Amalekites.) These codes are usually administrated by men. Controllers are always jumpy about the possibility of mutiny among the controlled. So a woman is approved as long as she adheres to the codes and the rules. If she steps outside those bounds, for example by living alone with no man to ‘govern’ her, or by performing cures or charms independently of the church’s rules, these will be disapproved. Her knowledge and supposed powers, not being monitored and channelled by the officials of God, must – the logic proceeds – come from the Other Place. Many a widowed or single woman, struggling to support herself in one of the few practical ways available to her in a man’s world, must have crossed this boundary from sheer necessity as much as from choice.

A couple of years ago, some children came to visit us whose parents are delightful born-again Christians. I suggested putting on a Disney video to keep them entertained, and their mother hesitated. Which one did I have in mind? Knowing that anything involving a witch would be disallowed, I did a rapid mental check – not ‘The Little Mermaid’, then, which has the Sea Witch – not ‘Snow White’ –

“The Sword in the Stone?”

She shook her head. “There’s a wizard in it.”

“But – the wizard’s Merlin – he’s a good wizard!”

“But his powers don’t come from Christ,” she said gently.

Well, the children watched “The Incredibles” instead, and I refrained from pointing out that the ‘Incredible’ powers enabling the characters to run like the wind, extend rubbery arms down entire blocks, become invisible, or whatever it is, might just as well be termed magic. It’s all in the name, it seems.

I often wonder how a religion whose founder Christ once said ‘By their fruits ye shall know them’, and who told the parable of the Good Samaritan with the specific message that goodness can come in the shape of the person you are most prejudiced against, has so much trouble with the Harry Potter books. Surely what’s important is to recognise goodness in whatever shape it comes, even if it happens to be wearing a pointed black hat at the time?

Illustration shows William Blake's 'The Witch of Endor' - and do check out this wonderful collection of other witch-related art: Witches and Apparitions at the National Gallery

Sunday, 8 August 2010

Where beth they beforen us weren?

This was something that happened in our village last year, and I talked about it on the Awfully Big Blog Adventure. (Funnily enough, only a few days later a really huge Anglo Saxon treasure was discovered up in the Midlands. This was not it.) I make no apology for reposting here what I said then, because no rewritten account could give the sense of immediacy and excitement we felt. It seems like time for an update, though, as if you click on the link at the bottom of this post you'll find pictures of the excavation, and the amazing Anglo Saxon brooch that was found. Plus some of the early suppositions (about the sex of the skeleton, for instance) turned out to be wrong.

I took a brisk walk out this morning to the Anglo-Saxon grave.

It was only discovered yesterday. We were out for an afternoon stroll in the mellow sunshine, taking a lane that runs out of the village towards the Downs in the distance, when we realised the wide, flat fields were full of widely separated, slowly walking figures (some women, but mostly men) with bowed heads, swinging long metal detectors like oddly shaped proboscises. Every so often one would stop and dig a little hole, pick something up, then wander on. The big farm was running a metal detectors’ rally, proceeds of the camping fees to cancer research.

We started talking to some of the men. One pulled out a wallet and showed us a medieval silver penny. Another had more pennies, Roman and medieval: and belt buckles: and buttons. ‘And over there,’ they all said, pointing towards the furthest field behind a belt of trees – ‘over there, that’s where they’ve found an Anglo Saxon grave!’

Everyone was alight with it. A huge gold brooch had been found, together with some bones. The police had been called immediately and had thrown a cordon around the site. The archeologists were already examining the brooch, which was over in the marquee beside the farm. We headed back to look for ourselves, on the way chatting to a group of three men who wouldn’t have seemed at all out of place at a Saxon chieftain’s burial. Big lads, with acres of tattoos. One had long black hair, another a shaved head. One wore an enormous plaited gold ring on his thick forefinger.

‘Any luck?’ we asked. They were friendly, shook their heads: ‘Nah. Only rubbish today. Here’s what we got, on this table over here, take a look if you like.’

‘If you want some, have some,’ added the black-haired man. ‘It’s rubbish. It’s all going in the bin otherwise. But have you heard about the gold brooch?’

On the table was a clutter of stuff. Bits of pottery, coins, harness buckles, buttons, crumpled tin and lead. ‘Take it! Take it all!’ exclaimed the black-haired man. He shovelled it all into a plastic container. It was heavy.

‘When you start this game,’ explained the man with the gold ring, ‘you’re really excited about a coin or two, but then you get ambitious. Tell them about that ring you found.’

‘18th century, with seven diamonds,’ said the man with the black hair.

‘We’ve all found rings, one time or another,’ said Gold RingMan.

We went on down to the tent. The brooch was there on display. It was the size of a large jam-pot lid, with a white coral boss surrounded by an inlay of flat, square-cut, dark red garnets. Around that, a broad band of bright yellow gold, with four set garnets standing out from it. Then more coral. And around that, a ring of intricate silver filigree, now black and dirty. People pored over it, photographed it, stared at it with awe, excitement, and reverence.

‘There’ll be another one,’ the archaeologist was saying. ‘They always come in pairs.’ And he had a look at the ‘rubbish’ the big guys had let us take away. It included four Roman coins, a bit of a medieval ring brooch, some Roman pottery, a lead musket ball the size of a marble - cold and heavy in the hand - and an 18th century thimble. Just a tiny fraction of what still lies under the dusty ploughlands.

So this morning, as I was saying, I walked out to see the site of the grave. Our village is probably Anglo Saxon in origin. The site was about two miles out from the farm, along a flat and dusty track between the fields, tucked away behind a strip of woodland, with a view of theDowns three miles away. It was marked out with striped tape, like a crime scene, and guarded by police vehicles. One of the archeologists gave me a lift the last quarter mile.

‘We think it’s a high status chieftain,’ she said. ‘Seventh century. We’ve found bones. We think it’ll be a major excavation.’

I stood there, in the sunshine and the light wind, looking at the place where, thirteen centuries ago, some Saxon warrior was laid to rest, and I had a lump in my throat.

Where beth they beforen us weren,

Houndes ladden and hawkes beren,

And hadden feld and wood?

I keep being told by my editor that there’s no market for historical children’s fiction; that it’s difficult to sell. Well, all I can say is, most of the people I met and talked to out on the fields yesterday were enthralled not merely by the idea of treasure hunting, but by the romance of the past. And well they might be, because this isEngland

Where, asks the anonymous Middle English poet, are they who were here before us, who once led their hounds and carried their hawks and owned both field and wood?

Still here, it seems, is the answer.

They’re still here.

It was only discovered yesterday. We were out for an afternoon stroll in the mellow sunshine, taking a lane that runs out of the village towards the Downs in the distance, when we realised the wide, flat fields were full of widely separated, slowly walking figures (some women, but mostly men) with bowed heads, swinging long metal detectors like oddly shaped proboscises. Every so often one would stop and dig a little hole, pick something up, then wander on. The big farm was running a metal detectors’ rally, proceeds of the camping fees to cancer research.

We started talking to some of the men. One pulled out a wallet and showed us a medieval silver penny. Another had more pennies, Roman and medieval: and belt buckles: and buttons. ‘And over there,’ they all said, pointing towards the furthest field behind a belt of trees – ‘over there, that’s where they’ve found an Anglo Saxon grave!’

Everyone was alight with it. A huge gold brooch had been found, together with some bones. The police had been called immediately and had thrown a cordon around the site. The archeologists were already examining the brooch, which was over in the marquee beside the farm. We headed back to look for ourselves, on the way chatting to a group of three men who wouldn’t have seemed at all out of place at a Saxon chieftain’s burial. Big lads, with acres of tattoos. One had long black hair, another a shaved head. One wore an enormous plaited gold ring on his thick forefinger.

‘Any luck?’ we asked. They were friendly, shook their heads: ‘Nah. Only rubbish today. Here’s what we got, on this table over here, take a look if you like.’

‘If you want some, have some,’ added the black-haired man. ‘It’s rubbish. It’s all going in the bin otherwise. But have you heard about the gold brooch?’

On the table was a clutter of stuff. Bits of pottery, coins, harness buckles, buttons, crumpled tin and lead. ‘Take it! Take it all!’ exclaimed the black-haired man. He shovelled it all into a plastic container. It was heavy.

‘When you start this game,’ explained the man with the gold ring, ‘you’re really excited about a coin or two, but then you get ambitious. Tell them about that ring you found.’

‘18th century, with seven diamonds,’ said the man with the black hair.

‘We’ve all found rings, one time or another,’ said Gold Ring

We went on down to the tent. The brooch was there on display. It was the size of a large jam-pot lid, with a white coral boss surrounded by an inlay of flat, square-cut, dark red garnets. Around that, a broad band of bright yellow gold, with four set garnets standing out from it. Then more coral. And around that, a ring of intricate silver filigree, now black and dirty. People pored over it, photographed it, stared at it with awe, excitement, and reverence.

‘There’ll be another one,’ the archaeologist was saying. ‘They always come in pairs.’ And he had a look at the ‘rubbish’ the big guys had let us take away. It included four Roman coins, a bit of a medieval ring brooch, some Roman pottery, a lead musket ball the size of a marble - cold and heavy in the hand - and an 18th century thimble. Just a tiny fraction of what still lies under the dusty ploughlands.

So this morning, as I was saying, I walked out to see the site of the grave. Our village is probably Anglo Saxon in origin. The site was about two miles out from the farm, along a flat and dusty track between the fields, tucked away behind a strip of woodland, with a view of the

‘We think it’s a high status chieftain,’ she said. ‘Seventh century. We’ve found bones. We think it’ll be a major excavation.’

I stood there, in the sunshine and the light wind, looking at the place where, thirteen centuries ago, some Saxon warrior was laid to rest, and I had a lump in my throat.

Where beth they beforen us weren,

Houndes ladden and hawkes beren,

And hadden feld and wood?

I keep being told by my editor that there’s no market for historical children’s fiction; that it’s difficult to sell. Well, all I can say is, most of the people I met and talked to out on the fields yesterday were enthralled not merely by the idea of treasure hunting, but by the romance of the past. And well they might be, because this is

Where, asks the anonymous Middle English poet, are they who were here before us, who once led their hounds and carried their hawks and owned both field and wood?

Still here, it seems, is the answer.

They’re still here.

And here is the link to see more pictures of the brooch, the burial, and the story of the excavation: Saxon Grave

Thursday, 5 August 2010

"Black Beauty meets Gladiator"

As a little break from more formal posts, I have two things to tell you. The first is odd: I woke up this morning dreaming that the London Times leader was all about the NEXT BIG THING in children's publishing: a book called 'Willoughby and the Time Watch', and a comic strip book about Tony Blair and the Iraq war; presumably highly metaphorical since the illustration showed a large purple dragon chewing ivy off a ruined turret. Make what you can of that.

Unless anyone out there is actually writing 'Willoughby and the Time Watch'? In which case - my friend, the omens are good!

The second thing I want to tell you is that the British fantasy writer Katherine Roberts is beginning a series of blog posts about the genesis and writing process of her (extremely good) book 'I Am The Great Horse' - the story of Alexander the Great seen through the eyes of his famous horse Bucephalus. (She jotted the idea down in her notebook as 'Black Beauty meets Gladiator'!) Katherine is not only an excellent writer and meticulous reseacher, but has a special affinity with horses as she used to exercise racing horses - professionally. The series looks set to be a really intriguing behind-the-scenes peek at how a writer works. Do go and visit her at Reclusive Muse

Unless anyone out there is actually writing 'Willoughby and the Time Watch'? In which case - my friend, the omens are good!

The second thing I want to tell you is that the British fantasy writer Katherine Roberts is beginning a series of blog posts about the genesis and writing process of her (extremely good) book 'I Am The Great Horse' - the story of Alexander the Great seen through the eyes of his famous horse Bucephalus. (She jotted the idea down in her notebook as 'Black Beauty meets Gladiator'!) Katherine is not only an excellent writer and meticulous reseacher, but has a special affinity with horses as she used to exercise racing horses - professionally. The series looks set to be a really intriguing behind-the-scenes peek at how a writer works. Do go and visit her at Reclusive Muse

Sunday, 1 August 2010

Childhood writing

I can’t remember a time in my life when I wasn’t writing. My mother wrote; my grandmother wrote: it always seemed an occupation as natural as breathing. Back in my early schooldays, the emphasis was always on reading and writing. (Arithmetic fell on stony ground.) Fairytales, poems and Bible stories went in, and poems, descriptions and stories flowed out.

I still have an exercise book from when I was about eight. Remember those lined exercise books, with their supple paper covers in dusty blues, maroons or greys, two staples in the spine? The teachers cut them in half to make two smaller books with one staple each. On each page we wrote what were termed stories, but really they were only a couple of lines long:

I have a little DOG who looks like a big baby her name is Lassie and I play with her and at night wen the gas fire is lit she lies down flat on the floor.

The moon is rising in the sky wen I look out of the window. It looks just like a silver ball floting jently in the sky

“Floating gently like a silver ball…” I was the same writer then that I am now.

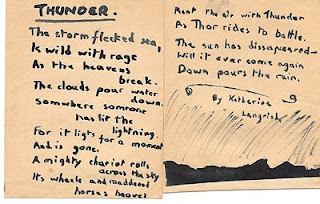

When I was nine I began writing poetry. I’d heard that Shakespeare was the greatest English poet, but he’d died hundreds of years ago. Nobody had written better poetry since then? Look out world, I thought, here I come! I’d need to practise, of course, I knew that: but I reckoned that by the time I was grown up, I would probably be at least as good as Shakespeare. I spent my time reading, writing, and riding ponies. My schoolfriends admired my stories, especially if they were about horses – or later, about ethereal love affairs between lords and ladies ‘as beauteous as the stars’. I was rubbish at all subjects except English and Art, but in those I was sure I was good. Have at look at this epic treatment of thunder: Thor and all...

As you can see, I didn't have the natural lyricism that many child poets have. I think I was already struggling to be 'literary'. Perhaps I read too much (lots of 19th century poetry from The Children's Encyclopaedia: I remember particularly admiring Byron's heavily overdone 'Mazeppa's Ride').

In order to become the new Shakespeare, of course, I would have to write a play or two. My verse drama career kicked off (and ended) with an adaptation – don’t laugh too hard – of ‘The Lord of The Rings’ in pantomime couplets. I took this very seriously. My group of friends was going to act it out in the apple loft of our barn (we lived in the country); and we spent ages making costumes out of curtains. The script has long since vanished, but I can still remember two lines from the play. Frodo and Sam are struggling across Mordor, and Frodo pauses to exclaim:

“The Dark Tower seems – ah! – just as far away.

We’ll reach it not tomorrow, ne’er mind today!”

Pretty good, huh? See that neat poetical inversion, and the apostrophe? I can’t remember now if the play was ever put on - probably not; I think our parents weren't that supportive - but we got some fun out of the rehearsals. And meantime I was writing a book of short stories about magic. It was springtime: I used to sit outside scribbling, and the sunshine and the celandines somehow found their way into the stories.

“Once there was a golden land, full-filled with mirth and joy

And in that land a lady lived, more beauteous than the stars,

And she took joy in simple things

Like butterflies with coloured wings

And little flowers, and green green grass,

And crickets’ chirp, and birdsong…”

I'm not sure I've ever been happier. Oh, it’s bad, I know it’s bad! But I didn’t know that then. All I knew then was that I was writing my absolute best: and to this day I don’t know a better feeling.

Soon after that I began a series of discoveries. I discovered Alan Garner, and started writing a long story based on ‘Celtic’ mythology. I discovered Rupert Brooke, and threw myself into sonnets beginning with lines like: Dream-like on the broad river drifting slow… I discovered Mary Renault and tried my hand at historical fiction. And, somewhere along the line, I discovered how to be self-critical…and the gates of the Garden of Eden shut behind me.

I still have an exercise book from when I was about eight. Remember those lined exercise books, with their supple paper covers in dusty blues, maroons or greys, two staples in the spine? The teachers cut them in half to make two smaller books with one staple each. On each page we wrote what were termed stories, but really they were only a couple of lines long:

I have a little DOG who looks like a big baby her name is Lassie and I play with her and at night wen the gas fire is lit she lies down flat on the floor.

The moon is rising in the sky wen I look out of the window. It looks just like a silver ball floting jently in the sky

“Floating gently like a silver ball…” I was the same writer then that I am now.

When I was nine I began writing poetry. I’d heard that Shakespeare was the greatest English poet, but he’d died hundreds of years ago. Nobody had written better poetry since then? Look out world, I thought, here I come! I’d need to practise, of course, I knew that: but I reckoned that by the time I was grown up, I would probably be at least as good as Shakespeare. I spent my time reading, writing, and riding ponies. My schoolfriends admired my stories, especially if they were about horses – or later, about ethereal love affairs between lords and ladies ‘as beauteous as the stars’. I was rubbish at all subjects except English and Art, but in those I was sure I was good. Have at look at this epic treatment of thunder: Thor and all...

As you can see, I didn't have the natural lyricism that many child poets have. I think I was already struggling to be 'literary'. Perhaps I read too much (lots of 19th century poetry from The Children's Encyclopaedia: I remember particularly admiring Byron's heavily overdone 'Mazeppa's Ride').

In order to become the new Shakespeare, of course, I would have to write a play or two. My verse drama career kicked off (and ended) with an adaptation – don’t laugh too hard – of ‘The Lord of The Rings’ in pantomime couplets. I took this very seriously. My group of friends was going to act it out in the apple loft of our barn (we lived in the country); and we spent ages making costumes out of curtains. The script has long since vanished, but I can still remember two lines from the play. Frodo and Sam are struggling across Mordor, and Frodo pauses to exclaim:

“The Dark Tower seems – ah! – just as far away.

We’ll reach it not tomorrow, ne’er mind today!”

Pretty good, huh? See that neat poetical inversion, and the apostrophe? I can’t remember now if the play was ever put on - probably not; I think our parents weren't that supportive - but we got some fun out of the rehearsals. And meantime I was writing a book of short stories about magic. It was springtime: I used to sit outside scribbling, and the sunshine and the celandines somehow found their way into the stories.

“Once there was a golden land, full-filled with mirth and joy

And in that land a lady lived, more beauteous than the stars,

And she took joy in simple things

Like butterflies with coloured wings

And little flowers, and green green grass,

And crickets’ chirp, and birdsong…”

I'm not sure I've ever been happier. Oh, it’s bad, I know it’s bad! But I didn’t know that then. All I knew then was that I was writing my absolute best: and to this day I don’t know a better feeling.

Soon after that I began a series of discoveries. I discovered Alan Garner, and started writing a long story based on ‘Celtic’ mythology. I discovered Rupert Brooke, and threw myself into sonnets beginning with lines like: Dream-like on the broad river drifting slow… I discovered Mary Renault and tried my hand at historical fiction. And, somewhere along the line, I discovered how to be self-critical…and the gates of the Garden of Eden shut behind me.