I went into ‘The Last Bookshop’ in Oxford the other day,

which sells what I assume (?) are remaindered books, since everything in the shop,

regardless of size or original price, is sold for two pounds. I buy books regularly

enough that I don’t feel guilty about getting them cheap from time to time: and anyway

the selections here are sometimes more interesting than what is to be found in the chains.

Which proved to be the case as I pounced with delight upon this:

It’s the third in a series of horse

books for children, 'The Horses of Oak Valley Ranch', by Jane Smiley, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of ‘A Thousand Acres’. I have the first two in the US hardcover

editions: ‘A Good Horse’ and ‘The Georges and the Jewels’. Faber and Faber in

the UK have changed these titles - in a way that links them more clearly as a series - to the more generic ‘Secret Horse' and ‘Nobody's Horse’. ‘Mystery Horse’ is called

‘True Blue’ in the States, and there are two more, which I look forward to reading.

|

| US title/cover |

|

| UK title/cover |

Take a look at the UK cover of 'Mystery Horse' - the gorgeous galloping grey horse against the blue sky, with a blue foil title,

and little blue and pink foil flowers scattered around. Any pony-mad child

would want it. And then – well, then

they might find this is more than your average pony story.

Set in 1960’s California,

the books follow the story of a young girl, Abby, growing up in a

fundamentalist Christian family. Her father is a horse trainer and dealer, and

Abby spends much of her free time outside school helping him work with the

horses. Her mother and father are loving parents but her father in particular

is unbending in his outlook, and her elder brother Danny has left home after a bitter row.

Smiley’s treatment of the family and its predicament is

sympathetic and nuanced. As Abby is the

narrator, we see her father through her eyes: stubborn, hardworking, fair

according to his lights, rigid in his beliefs but – over the course of the

first three volumes – able finally to compromise and come to terms with his son’s

independence. In the meantime Abby

begins to navigate her own way through life. Observing her father’s strengths

and weaknesses, she learns how to trust herself, to question her parents’ views

without loss of love or respect, and to come to her own conclusions.

|

| US title/cover |

|

| UK title/cover |

And YES, there is a lot about horses. Horses, Smiley

suggests, are much like people. When her father, a church elder, wants to

discipline the disruptive young sons of a church family, Abby points out that

whipping a child can be as counterproductive as whipping a horse:

“I think they [the boys] are like

Jack, not like Jefferson. If we whipped Jack,

it wouldn’t make him stop running. It

would make him run faster. If we whipped

Jefferson, he might not run at all. He might just stop and buck.”

Mom reached over and smoothed my hair. Dad didn't say anything, and we drove the rest of the way home.

As if all this wasn’t enough, ‘Mystery Horse’/’True Blue’ is

also a remarkably good ghost story: unsettling, spooky, beautiful and

ultimately all about Abby – so that

the ghostly bits are integral to the narrative and not some tacked-on extra

thrill.

As an adult, I love these books. I love the detailed and

thoughtful accounts of grooming, training and riding these horses which –

because they are all for sale – often don’t even have individual names, in case

anyone gets too attached to them. I love the fact that there

can be whole chapters set in church – the ‘church’ which is all this small

faith group can afford, a featureless rented space in a shopping mall. I love the thoughtfulness with which Jane

Smiley navigates Abby’s world. The ways

in which school and home life clash: textbooks which mention evolution and therefore

cannot be shown to Daddy, or Mom’s horror on discovering that in a history

lesson, Abby has been constructing cardboard models of Spanish missions.

‘“You built a Catholic

mission?”

“We all did.”’

It’s done with

a light, almost comedic touch, but can become serious. ‘“So,” said Daddy' [to

Daniel, at the beginning of their quarrel]. “Some boys who taught you to take the holy name of the Lord in vain

are going to pick you up and take you to see a fantasy movie about evil and

hate. Am I right?”’ Other kids are

allowed to go to movies and listen to the Beatles. Abby doesn’t exactly miss these

activities, but she knows that not having them makes her different.

I love all of this. But would a child?

Well, it depends on the child. And this is where the title for this post

comes in. Genre fiction has an

undeserved bad name. Horse and pony books. School stories. Crime. Romance. Historical novels.

Science fiction. Fantasy. Children’s books. If you can put it in a category, it must

somehow be less than a ‘real’ novel.

‘It’s just a pony book.’ ‘It’s

just a school story. ‘It’s just a

romance.’

It’s true that there are many pony books, school stories

or adventure stories which are hardly great literature, however that may be

defined. But not every plain old novel is great literature either. I’m not

denigrating the many, many pony books I read as a child just because, as an adult, I no

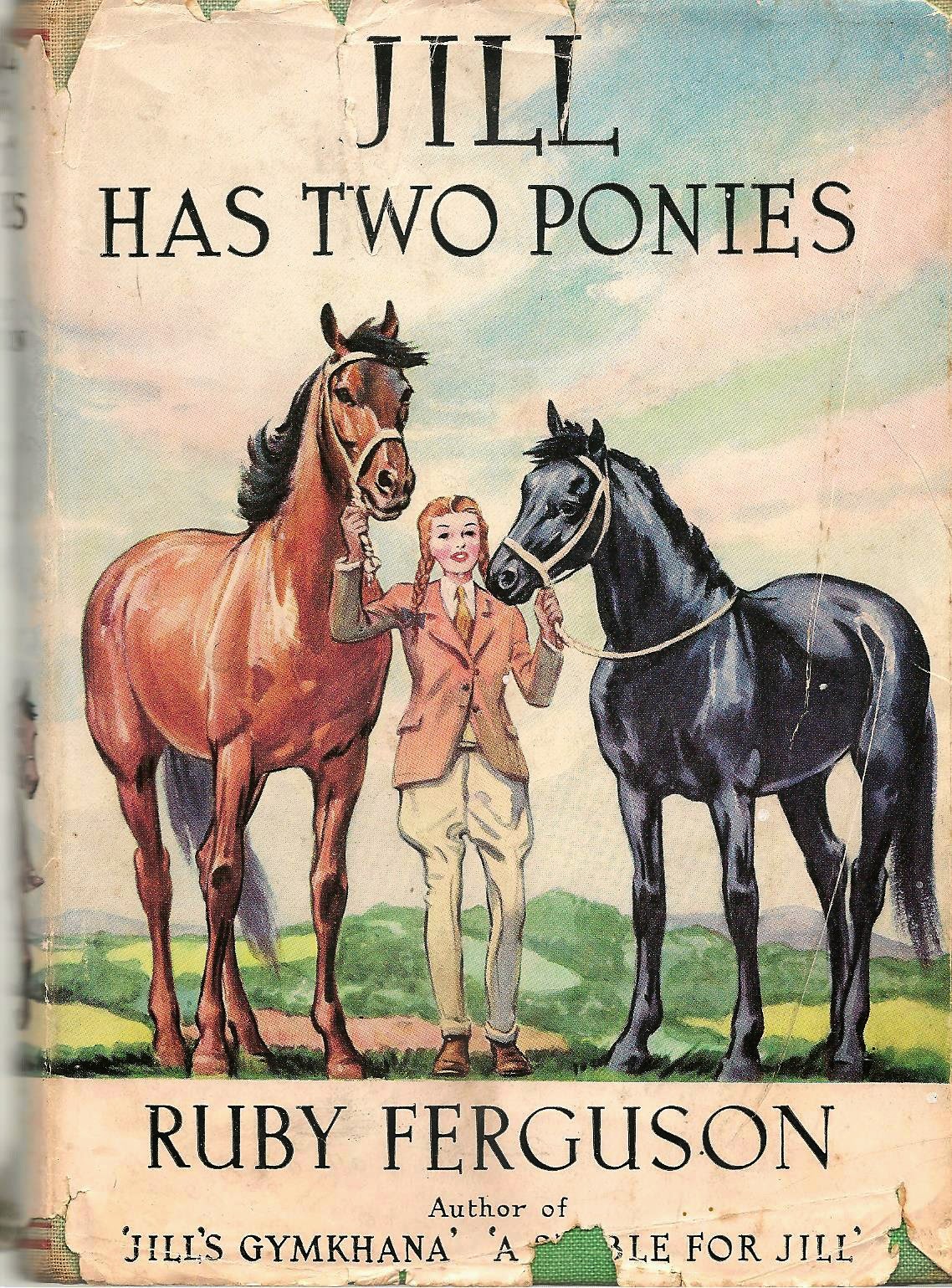

longer find them so interesting. The ‘Jill’ books by Ruby Ferguson, for example,

kept me enthralled when I was ten or eleven. They are fun, they are lively. They do one single thing:

tell an entertaining story and tell it well.

That is good in itself.

But there are books which do more, which are

multi-dimensional. Mary O’Hara’s ‘My Friend Flicka’ and ‘Thunderhead’ and

‘Green Grass of Wyoming’ are multi-dimensional. They offer a richness – of

characterisation, of description, of emotional intelligence – which the ‘Jill’

books don’t have and never aspired to.

KM Peyton’s ‘Flambards’ and ‘Fly

By Night’ and ‘The Team’ are multi-dimensional. In the genre of ‘school story’,

Enid Blyton’s ‘Malory Towers’ and ‘St Claire’s’ stories offer the child reader excellent ripping

yarns, unashamed fantasies of the fun and frolics of boarding-school life. But

Antonia Forest’s school stories ('Autumn Term' and its sequels) are multi-dimensional. They offer more: depth

of character, growth, change, consideration of topics such as religion,

censorship, responsibility, and the unwitting cruelty of schoolchildren to

persons they dislike.

And yes, I loved all of them indiscriminately, but the ones I read and reread

and have kept reading into adult life are the multi-dimensional books. I knew even back at the age of eleven or

twelve or thirteen that I was getting far, far more out of ‘My Friend Flicka’

than I was getting out of ‘Jill’s First Pony’.

Mary O’Hara was talking about stuff that was important to me. My father and my brother, much as they loved

each other, used to argue. There were misunderstandings, jealousies, quarrels which

sometimes burst around us with the violence of a thunderstorm. In ‘My Friend Flicka’ and its

sequels, the dreamy boy Ken and his impatient, practical father are also

negotiating a difficult relationship punctuated by storms. That story intertwines with the story of

Ken’s love for his little horse, and is equally important.

Maybe some children don’t like these multi-dimensional

books, maybe some children – perhaps even many children? – become bored,

impatient, wanting simply to get on with the story. But there will be other

children who want more, who are already thinking, already asking questions about

life, who will appreciate finding these questions taken seriously in the

middle of a book ‘about’ horses or school. A multi-dimensional book always gives the reader

more than they expected.

Am I simply saying that genre books can be good novels? Of course I am. But it’s more than that. It’s a plea.

The next time you read an excellent horse story or school story or

fantasy, try not to say in its praise, ‘It isn’t just a pony book/school story, of

course…’ as if somehow it needs to be extracted from its lowly niche before it

can be appreciated. Worse still, don’t

say, ‘It’s not really a pony book/school story/children’s book at all!’

Because if you do, if everyone who ever reads and loves a ‘genre’ book

feels they have to rescue it from its category before praising it,

then what is left? Every category of books – novels,

children’s fiction, popular science, you name it – contains a multiplicity of less or more able writers, and we should remember it's better do something simple and do it well, than to aim high and fail. If

somebody says, as someone recently said to me, ‘But Ursula le Guin’s books

aren’t really fantasies’, how is that a compliment to le Guin, who chose to

employ her wonderful talents in the field of sci-fi and fantasy? All it

really proclaims is the reader’s embarrassment at having enjoyed a

book belonging to a genre which they believe - in spite of the evidence before their eyes - to be second-rate.

Either we need to do away with categories and genres

altogether – which isn’t going to happen – or we need to stop being

embarrassed and apologetic, and be ready to recognise and celebrate good work in whatever field it happens to grow. Loud and clear: there are excellent pony

books, there are excellent school stories, there are excellent fantasies, and there are excellent children’s

books. Their excellence is no different

in kind from that of any other writing. So, yes! Unsurprisingly, Jane Smiley's series of horse

stories is truly excellent. Any child or adult who picks them up will learn much – about horses,

and about life.