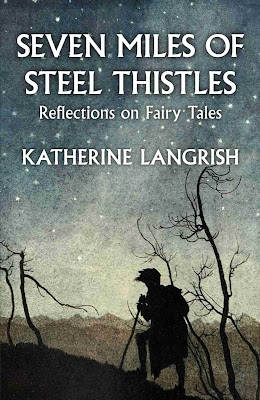

My book on fairy tales, ‘Seven Miles of Steel Thistles’ (of course named after this blog) was first published in 2016 by the Greystones Press and is now available again on Amazon in paperback as well as an e-book: click this link!

This is the opening essay:

I’ve loved fairy tales all my life. I was lucky enough to grow up in a house full of books, and though I can remember learning how to write, I have no memory at all of learning to read; it seemed something I was born doing. As a child I felt incomplete without a book in my hand and as often as not, that book would be full of fairy tales. Soon I was also reading legends and myths from around the world. I chose the Norse myths for a school project, retelling and illustrating stories about Thor, Odin and Loki. I read the tales of King Arthur; I read the Arabian Nights. And, though I hardly know how, I gradually became aware of distinctions between these, to me, very similar genres. Some were taken more seriously than others. Myths were at the top, legends came next, fairy tales were the poor cousins at the bottom. ‘Greek myths’ weren’t fairy tales: they were supposed to be more important than that. Yet there seemed to be a considerable overlap. Andrew Lang included the story of Perseus and Andromeda in The Blue Fairy Book, under the title The Terrible Head. And surely he was right. It is a fairy tale, about a prince who rescues a princess from a monster! In a story book handed down from my mother I read three tales by Nathaniel Hawthorne: ‘The Inquisitive Girl’, ‘The Golden Touch’, and ‘The Pomegranate Seeds’. These were retellings of the myths of Pandora, King Midas, and Proserpina, but they were indistinguishable from fairy tales.

The field of fairy stories, legends, folk tales and myths is like a great, wild meadow. The flowers and grasses seed everywhere; boundaries are impossible to maintain. Wheat grows into the hedge from the cultivated fields nearby, and poppies spring up in the middle of the oats. A story can be both things at once, a ‘Greek myth’ and a fairy tale too: but if we’re going to talk about them, broad distinctions can still be made and may still be useful. Here is what I think: a myth seeks to make emotional sense of the world and our place in it. Thus, the story of Persephone’s abduction by Hades is a religious and poetic exploration of winter and summer, death and rebirth. A legend recounts the deeds of heroes, such as Achilles, Arthur or Cú Chulainn. A folk tale is a humbler, more local affair. Its protagonists may be well-known neighbourhood characters or they may be anonymous, but specific places become important. Folk narratives occur in real, named landscapes. Green fairy children are found near the village of Woolpit in Suffolk – according to the medieval chonicler Ralph of Coggeshall. In a tale made famous by Alan Garner, a Cheshire farmer going to market to sell a white mare meets a wizard, not just anywhere, but on Alderley Edge between Mobberley and Macclesfield. In Dorset an ex-soldier called John Lawrence sees a phantom army marching ‘from the direction of Flowers Barrow, over Grange Hill, and making for Wareham.’ Local hills, lakes, stones and even churches are explained as the work of giants, trolls or the Devil.

Fairy tales can be divided into literary tales – the more-or-less original work of authors such as Hans Christian Andersen, George MacDonald and Oscar Wilde, which will not concern me very much in this book – and anonymous traditional tales, originally handed down the generations by word of mouth but nowadays usually mediated to us via print. Unlike folk tales, traditional fairy tales are usually set ‘far away and long ago’ and lack temporal and spatial reference points. They begin like this: ‘In olden times, when wishing still helped one, there lived a king…’ or else, ‘A long time ago there was a king who was famed for his wisdom through all the land…’ A hero goes travelling, and ‘after he had travelled some days, he came one night to a Giant’s house…’ We are everywhere or nowhere, never somewhere. A fairy tale is universal, not local.

Characters in fairy tales rarely possess names: when they do, these are either descriptive, like ‘Little Red-Cap’ and ‘Snow-White’, or else extremely common, such as Gretel, Hans, Kate, Jack. The effect is inclusive: these are the adventures of Everyman and Everywoman; but most of the time fairy tale characters are referred to even more generically, as ‘the king’s daughter’, ‘the boy’, ‘the maiden’, ‘the soldier’, ‘the tailor’ and so on.

None of the traditional forms – myth, legend, folk or fairy tale – can or should be approached in the same way that we approach a novel. They are not, for example, the least little bit interested in building characters’ inner lives. Fairy tale characters are established briefly, succinctly and once for all: ‘a dear little girl’, ‘a poor old woman’, ‘two daughters, one ugly and wicked, the other beautiful and good’. That’s it, set in stone. They won’t develop or change, and everything that happens to them happens on the outside. Again, though fairy tale narratives operate perfectly well by their own sets of rules (the third son is the lucky one; kindness to an animal wins you a magical helper) these are not the rules we expect from a novel. At the beginning of her story, Snow-White is a child of seven. By the end, she marries the prince. So… how old is she now? How long did she keep house for the dwarfs; how long has she lain in the glass coffin? Is this a lingering memory of some dark practice of child brides? It’s a mistake to ask. It’s a category error to look for that kind of consistency in a fairy tale. Snow-White is old enough to marry the prince at the end of the story for no other reason than that the narrative demands she should be. That is how the story ends.

Plenty of traditional fairy tales contain no actual fairies at all. (Unless you count the dwarfs, there are none in Little Snow-White, for example.) The term ‘fairy tale’ seems to have originated with Madame d’Aulnoy’s Les Contes de Fées or ‘Tales of the Fairies’, published in 1697. According to the well-known fairy-tale scholar Jack Zipes, ‘By the time of her death a few years later… d’Aulnoy’s name had become synonymous with an expression she was the first to use – contes de fées.’ Madame d’Aulnoy’s sophisticated, literary, fanciful stories feature characters such as the amiable Fairy Gentille or the wicked Fairy Carabosse, who help or harm the fortunes of pairs of delightful young lovers. The magic in these tales is consciously amusing: in The Blue Bird, for example, King Charming rides in a chariot drawn by winged frogs, and shouts, ‘My frogs! My frogs!’ when he wishes to depart. Good and bad fairies make appearances in many of Charles Perrault’s tales (also published in 1697, a good year for the genre) but certainly not in all: there are none in Little Red Riding Hood or Bluebeard, for example. Perhaps reflecting this, Perrault’s collection is called simply Histoires ou contes du temps passé, ‘Stories or tales of long ago’. And in 1810 Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, whose interest was in the origins of traditional German tales, gave to their own collection the unassuming title Kinder- und Hausmärchen, ‘Children’s and Household Tales’. There are fewer fairies to be found in the Grimms’ tales than there are witches and wicked stepmothers, but English translations persist in calling them ‘fairy’ tales. And why not? It’s what we’ve grown used to.

Of course, the Grimm brothers were an inspirational part of the great Europe-wide revival of interest in traditional tales that sprang up as part of the Romantic movement and of nascent nationalism. They set the standard for many other collectors throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, such as Ireland’s Thomas Crofton Croker and William Larminie, Norway’s Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, Romania’s Petre Ispirescu, and Russia’s Aleksandr Afanasyev. The world became a wilder, more magical place. Selkies plunged through the wild waves beyond Orkney. Undines drew themselves sinuously out of German rivers. The Neckan plucked his harp and sang mournfully on Scandinavian headlands and Baba Yaga flew through the Russian forests in her pestle and mortar to light down at her skull-bedecked garden gate.

At first, such stories were collected by adults and intended for adults. Sir George Webbe Dasent specifically forbids ‘good children’ to read the last two (mildly naughty) tales in Popular Tales from the Norse, his 1859 translation of Asbjørnsen and Moe’s Norske Folkeeventyr. Referring to himself in the third person, he writes in his introduction:

“He will never know if any bad child has broken his behest. Still, he hopes that all good children who read this book will bear in mind that there is just as much sin in breaking a commandment even though it not be found out, and so he bids them goodbye, and feels sure that no good child will dare to look into those two rooms.”Concern for children’s morals was to exercise many an editor in the decades to follow, most of whom trusted to censorship rather than simple appeals to honour. In 1889 Andrew Lang published The Blue Fairy Book, the first in his immensely successful series known as ‘the Coloured Fairy Books’. Actually his wife Leonora Blanche Alleyne was ‘almost wholly’ responsible for the selections and translations, as he himself acknowledged. Compiled specifically for children, they were collections of stories, both literary and traditional, from many different countries and cultures, lightly bowdlerised where necessary. Parents could be confident in their suitability, and children liked them because Mrs Lang’s choices were excellent and she didn’t preach. In his introduction to The Lilac Fairy Book, Lang struck hard at the ‘new’ fairy tales then being churned out for children’s consumption:

The three hundred and sixty-five authors who try to write

new fairytales are very tiresome. They

always begin with a little boy or girl who goes out and meets the fairies of

polyanthuses and gardenias and apple blossoms: ‘Flowers and fruits and other

winged things.’ These fairies try to be

funny, and fail, or they try to preach, and succeed. Real fairies never preach or talk slang. At

the end, the little boy or girl wakes up and finds that he has been dreaming.

Coincidentally, 1889 was also the year in which Lewis Carroll published Sylvie and Bruno, a book most people now find unreadable. In it, Carroll also took time to have a go at the moralising tone of late nineteenth century children’s fairy fiction:

I want to know – dear Child who reads this! – why Fairies should always be teaching us to do our duty, and lecturing us when we go wrong, and we should never teach them anything?

Sylvie and Bruno, 190

But he didn’t manage to avoid the pitfalls himself. We soon meet two tiny fairies, who are simply miniature children. Good little Sylvie is trying to turn over a big beetle struggling on his back: ‘it was as much as she could do, with both arms, to roll the heavy thing over; and all the while she was talking to it, half scolding and half comforting, as a nurse might do with a child that had fallen down.’ In contrast to kind Sylvie we next encounter naughty Bruno, who is busy tearing up Sylvie’s garden.

Think of any pretty little boy you know, with rosy cheeks, large, dark eyes and tangled brown hair, and then fancy him made small enough to fit comfortably into a coffee cup…

Sylvie and Bruno, 198

Bruno speaks in the lisping baby-talk which Victorian readers seem inexplicably to have found so appealing. ‘Revenge is a wicked, cruel, dangerous thing,’ Carroll-as-narrator tells the little fairy. ‘River-edge?’ Bruno responds. ‘What a funny word! I suppose oo call it cruel and dangerous ‘cause, if oo wented too far and tumbleded in, oo’d get drownded.’ This illustrates how difficult it must have been for Victorians to avoid gluey sentiment when writing about fairies for children. Even the creator of Alice couldn’t escape! To return to The Blue Fairy Book after this kind of thing is like striding out into open country and wild winds, and to realise what a great service the Langs did for nineteenth century children.

And although the Langs suppressed any hints of immoral behaviour in fairy tales, they were bracing in their attitude to violence. It was in The Blue Fairy Book that I first read the full version of Perrault’s The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood, with its thrillingly gruesome second half – these days usually omitted – in which the King’s ogress mother orders the young Queen and both her little children to be killed and cooked with sauce Robert (whatever that was). After a last-minute rescue, the wicked ogress is thrown into a pit full of toads and vipers. It was not for the faint-hearted. Whether the two halves of the story truly belong together or no, I loved it, and I appreciated its touches of macabre humour: the Sleeping Beauty may look young but she is actually a hundred and twenty, so ‘her flesh must be expected to be on the tough side’. My local library stocked all of the Coloured Fairy Books: Blue, Red, Green, Crimson, Yellow, Brown, Lilac, Violet… I read the lot. I read everything else, too, but fairy tales were a staple of my diet.

You couldn’t exhaust them, they were all so different. Some were quirky and funny, like Puss in Boots. Some, especially French stories like The White Cat or Beauty and the Beast, felt bright and light and pretty. The Grimms’ tales were dark and scary. Hans Christian Andersen’s stories were beautifully, deliciously sad. The poor little Mermaid! The poor little Match Girl! The poor little Fir-Tree! And sometimes they were horrifying, like The Red Shoes, the story of the vain girl whose red shoes dance her away without stopping, until she has to have both her feet chopped off by a woodcutter. I was about eight years old when I first read it, and unfortunately my mother had just bought me a pair of red leather shoes, which from then on I absolutely refused to wear.

If traditional fairy tales could be strong meat, in other children’s books I still met plenty of the soppy fairies so despised by Andrew Lang – fragile little creatures who danced on tiptoe, lived in flowers or under toadstools, and wore bluebell hats. I didn’t altogether mind them, but compared with real fairy tales, they were pretty tame. A good example is Pink Paint for a Pixie, a story by Enid Blyton in which a little girl loans her paintbox to a pixie and is rewarded when he paints the tips of the daisies pink so that she can make a magical necklace. Twentieth century fairies had ceased to preach, but they were always helpful: not for nothing did Lady Baden-Powell name her girl scout movement ‘The Brownies’ – after an earlier name, ‘The Rosebuds’, proved unpopular with girls. Brownies were presented as helpful domestic sprites (most unlike the unpredictable tricksters of folklore), and the traditional names for the Brownie ‘sixes’ when I joined briefly in the 1960s were Pixies, Elves, Leprechauns, Gnomes, Fairies and Sprites. Prejudice was rife – no one wanted to be a gnome – there were badges for feminine tasks such as knitting, sewing, and baking buns, and I left after a few weeks, partly because I did not believe I would ever learn to skip a hundred times backwards.

When I was about ten I discovered Alan Garner, who had burst upon the scene in 1960, raiding Celtic and Norse legends and throwing the booty together in the most electrifying way in his first book The Weirdstone of Brisingamen. Here, and in its sequel The Moon of Gomrath, two contemporary and quite conventional children – who might easily in other hands have seen fairies at the bottom of the garden – are hurled into a maelstrom of ancient magic, moon goddesses, shapeless terrors and hints of deeper worlds. A flood of magic from legend and folklore was released into children’s fiction, changing it forever. There are no obvious fairies in the books; the male supernatural characters consist of a wizard, some rather chilly elves, and dwarves: but Angharad Goldenhand, the lady of the lake, is a fairy queen in the style of the Mabinogion or the Morte d’Arthur, while her adversary the Morrigan is a witch-queen or crone worthy of Grimm. Yes, these characters are primarily intended to be perceived as aspects of the triple moon goddess, but that’s what all fairy queens in folklore and ballads may once have been. And fairies in folklore have always been connected with sex as well as death:

‘Harp and carp, Thomas,’ she said,

‘Harp and carp along with me,

And if you dare to kiss my lips.

Sure of your body I will be.’

So Thomas the Rhymer kisses the Queen of Elphame under the Eildon Tree and rides away with her through the river of blood into elfland. Wild Edric loses his fairy wife Godda and rides for ever on the Shropshire hills with his Hunt, searching for her. As for the sexy, beautiful, dangerous male faeries of modern teen novels, they find a traditional antecedent in the Irish Gancanagh, the ‘Love-Talker’, a beautiful fairy youth who waylays young girls in the gloaming and makes them so love-sick for him that they pine away and die.

The Irish have always remembered the dangerous side of the fairies. William Allingham’s fairies in Up the Aery Mountain, Down the Rushy Glen with its ‘Wee folk, good folk, Trooping all together, Green jacket, red cap, And white owl’s feather’ may fleetingly sound like Walt Disney’s dwarfs. But Allingham knew the connection of the fairies with loss and death:They stole little BridgetFor seven years long,And when she came down againHer friends were all gone. They took her lightly back,Between the night and morrow,They thought she was fast asleep,But she was dead from sorrow.

Scottish J.M. Barrie may have given us Tinkerbell in Peter Pan, but his second take on supernaturally extended youth is an eerie play about a girl stolen by the fairies, Mary Rose; and it doesn’t have a happy ending.

The variant spelling ‘faerie’ has recently almost entirely replaced ‘fairy’ in young adult fantasy fiction, probably in an effort to distinguish the human-sized, dangerous fairies of the Celtic tradition from the diminutive milk-and-water flower fairies of late nineteenth and early twentieth century children’s fiction. Spelt ‘faerie’, the word somehow just looks more magical, too – more romantic, more grown-up, more literary – conjuring ‘magic casements opening on the foam Of perilous seas, in faerie lands forlorn…’ Fairies, faeries, elves, whatever you like to call them, symbolize bereavement and death as well as the lure of love and beauty. That’s surely why the ballads divide the ‘high’ fairies into two ‘courts’: the ‘Seelie Court’ and the ‘Unseelie Court’, representing their benevolent and harmful aspects. European fairy culture is rich and complex. No wonder so many modern fantasy writers plunder it.

But let’s forget the ballads and romances and the heroic Celtic legends, and look once again at the humble fairy tale. People who dislike fairy tales (and probably seldom read them) complain that at best they are romantic trivia, at worst escapist nonsense with a side-order of sexism. Aren’t they all about princes rescuing passive princesses from dragons, giants and towers? How can any self-respecting adult defend that? If it were true, perhaps I couldn’t, but it is simply not so. The Grimms’ tales alone include many more stories about peasants and tradesmen, farmers, beggars and pensioned-off soldiers than they do about princesses and queens. And if you think about it for a moment, the world is still full of peasants and tradesmen, farmers and beggars and pensioned-off soldiers. Just as it always was.

Hansel and Gretel, as Adèle Geras has succinctly put it, is ‘about hunger’ – about the terrible choices people have to face when they are at starvation’s door. The Blue Light is about a soldier who’s done his duty by his country only to be discarded and marginalized and left to tramp the roads. The Seven Little Kids is about a single, working mother who has to leave her children alone in the house, knowing they may be in danger. (Yes, she happens to be a goat.) The Fisherman and his Wife is about greed (and a poisonous marriage). The Mouse, the Bird and The Sausage is a cautionary tale about the dangers of blind trust and naivety. There’s even a far-fetched yarn about organ transplants called The Three Army Surgeons.

As Alison Lurie says in her book of essays on children’s literature, Don’t Tell the Grown-Ups, fairy tales are much more realistic than you might think:

To succeed in this world you needed some special skill or patronage, plus remarkable luck; and it didn’t hurt to be very good looking. The other qualities that counted were wit, boldness, stubborn persistence and an eye to the main chance. Kindness to those in trouble was also advisable – you never knew who might be useful to you later on.

Don’t Tell the Grown-Ups, 18

Comical, tragic, beautiful or cruel, these anonymous stories are amazingly diverse and amazingly hardy. They’ve been told and retold, loved and laughed at, by generation after generation, because they are of the people, by the people, for the people. The world of fairytales is one in which the pain and deprivation, bad luck and hard work of ordinary folk can be alleviated by a chance meeting, by luck, by courtesy, courage and quick wits – and by the occasional miracle. The world of fairy tales is not so very different from ours.

It is ours.

Picture credit: 'Pixie' - woodcut by Dorothy P. Lathrop