When Katherine asked if I might like to write a blog post about my favorite fairy tale, I drew a blank. I’m almost afraid to admit this, but I didn’t like fairy tales when I was a kid. I thought they were dry, their characters two dimensional and their plots predictable. But as I wrote my e-mail, meaning to decline, one particular book did come to mind. It was Alice and Martin Provensen’s book of fairy tales, and I remembered it mainly for the illustrations, which were terrifying.

I asked Katherine if that sort of subject would do for a non-fairy tale reader and she said, yes. So . . .

This book sat on my shelf untouched for years. Too disturbing to read, too compelling to overlook, it was a gift and absolutely could not be sent off to the library book sale. No matter how many times I weeded my collection, it always remained. There on the shelf, with its dark mesmerizing illustrations in black and purple and virulent green.

Those of you familiar with the deeply charming Animals of Maple Hill Farm, or with A Visit to William Blake's Inn which won both the Newbery Award and a Caldecott Honor in 1982 might be surprised that anything by the Provensens could be that disturbing.

Yes, well they were always about more than cats and bunnies and talking sunflowers. In The Animals of Maple Hill Farm the Provensens introduce you to all the hens and roosters at their farm in a two page spread that includes examples of the obnoxious rooster, Big Shot, being nasty to the other roosters and bullying the hens, and then Big Shot gets carried off by a fox.

And no one minds, they say with a shrug.

Look through A Visit to William Blake’s Inn and notice the semi-circular smile on the Man in the Marmalade Hat. That's him on the left.

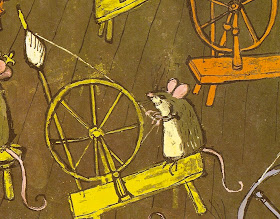

Observe his chiclet style teeth. Imagine an entire book peopled with those smiles and those teeth, and no friendly anthropomorphic sunflowers, either. The best you get is some malevolent looking mice.

A mouse from "The Forest Bride" by Parker Filmore.

This from the story “The Lost Half Hour” by Henry Beston:

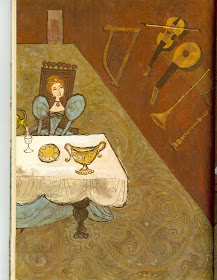

Or this from “Beauty and the Beast” by Arthur Rackham:

I couldn’t fit this into one scan, but if you look carefully you can piece together the composition with Beauty sitting at the table and the Beast lurking just around the corner. The Provensens have used the gutter between the pages to emphasize the corner in the image. The images aren’t merely frightening, they are brilliant and frightening. The hands of the beast are huge and clawed, yet they hang awkwardly, giving you the idea that in an unfortunate fumbling manner they might accidentally rip your arm off.

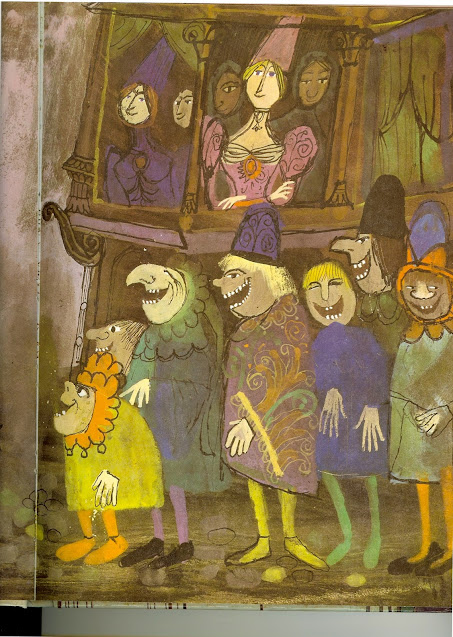

This is from the happy, upbeat (not), The Prince and the Goose Girl by Elinor Mordaunt.

Holy Cow. This book gave me the heebie-jeebies.

So, of course, I left it on the shelf when I grew up and moved out on my own. And I never read it when I visited home. No, never. And when I saw a copy at a thrift store, of course I said, “Oh, look!” And bought it instantly.

Okay, so there . . . there may be a contradiction there. And when I said the book sat on my shelf untouched? I lied. When I got the book home and looked through it, I remembered every single story. "The Lost Half Hour" where poor unfortunate Bobo is sent out by the Princess to find the half hour lost while she overslept. “Feather O’ My Wing” by Seamus McManus with the same spiteful stepsisters as “Beauty and the Beast,” but a story line a little more like “East of the Sun, West of the Moon.” Barbara Leonie Picard’s "Three Wishes" were the peasant boy gives away his hard earned wishes and receives them all back again.

And perhaps my favorite, “The Prince and the Goose Girl.” The heroine Erith is absolutely indomitable. She won’t back down, not even if it costs her life, and when the Prince realizes this he also realized that Erith is right that he isn’t much of Prince. Fortunately, he becomes a reformed man, and because Erith is as kind as she is brave, it all works out in the end.

Why, oh, why didn’t I think of "The Prince and the Goose Girl" when Katherine asked me to write a post?

I think the answer has something to do with the Introduction to the book, which may be the one part I really didn’t read. In the introduction Joan Bodger explains that these are literary fairy tales. The italics are hers, not mine and their elitism makes me uncomfortable, but I think Bodger is saying the same thing that I am struggling with. I didn’t like fairy tales when I was growing up because most of the things that were labeled “Fairy Tales” in my experience were those bowdlerized, dessicated versions that were three paragraphs long and came in books of a hundred or more and had absolutely no personality. Everything that gave them depth had been sifted out because it was rude, or it was frightening, or it made the story too long for its intended audience.

They were stripped down to their Propp’s morphology. I tend to think of them as skeletons of stories, but the Provensons remind me that they aren’t dead skeletons so much as a seed bank that any of us can draw on, and that when we do draw on this seed bank, what we are writing (with or without the upscale qualifier literary) is fairy tales.

Note from Katherine:

It's an honour to have Megan on the blog. In about 1998 I was living in America, in upstate New York, and one of the bolt-holes

for me and my two young daughters was the local Barnes and Noble

(conveniently close to Toys R Us and a miniature horse ranch). Trawling

the shelves one day - for myself, of course; the girls were in the

littlies section - I pulled out a book called 'The Thief' by Megan Whalen Turner.

It was a Newbery Honor book – I flicked it open and read a snippet –

and thus met her narrator Gen (short for Eugenides), who is languishing

in prison, loaded with chains, because:

...I had bragged without shame about my skills in every wine shop in the city. I had wanted everyone to know that I was the finest thief since mortal men were made…

...I had bragged without shame about my skills in every wine shop in the city. I had wanted everyone to know that I was the finest thief since mortal men were made…

Gen is truly an unreliable narrator – an infuriating, intelligent, secretive, multi-layered individual whom you get to like very much indeed. The book is set in an almost but-not-quite familiar early Mediterranean world, where gods are worshipped who resemble the Greek pantheon but are not – and where small city states war against one another, or form alliances, under the shadow of a powerful Eastern empire. 'The Thief' was followed by its sequels, ‘The Queen of Attolia’, ‘The King of Attolia’, and ‘A Conspiracy of Kings’ and from an impressive start they just get better and better. Beautiful writing. Lots of devious politics. Lots of twists. Unforgettable characters. I'm a huge fan, and I'm hoping there's going to be more...

I love "The Thief"! Also "Instead of Three Wishes", but Gen remains very high on my list of favorite fictional people. Every time I think I've got him figured out, I . . . don't.

ReplyDeleteAs for fairy tales, I loved them, but only because I could add in all of the missing details. One of my very favorites was "The Land of the Blue Flowers", by Frances Hodgson Burnett, because she made something that read like a fairytale but was more than that. It was an actual STORY, and not a poor sad skeleton of something, as most fairytales are.

I see your point about the bowdlerised stories - those giant books which are handy for bedtime reading by Mum or Dad, but don't leave much of the original. But really, most books of fairy tales were cut down for children in the 19th century and in some ways, all of them were "literary", even if they were folk tales rather than the short stories of Hans Anderson or Oscar Wilde. Perrault and the Grimms and others wrote their own versions. And I think Ashputtel and the English Tattercoats are much better versions of Cinderella than Perrault's, taking their love life into their own hands rather than waiting for a fairy godmother and then only getting the prince because she stuffed up her godmother's instructions. :-)

ReplyDeleteAs a child I read some Russian fairy tales I discovered in a library and simply loved the adventures of Prince Ivan and Baba Yaga with her mortar and pestle transport. And as an eight year old I read the Greek myths in their full, gruesome commentaried version by Robert Graves and was disappointed to find children's versions! Talk about bowdlerised!

Re-reading my own post, I don't think I've written (or figured out, even) how little the traditional forms of fairy tales moved me. Andrew Lang's Fairy books, for example, just never fired my imagination, but Tasha Tudor's retellings, did. Ryecik Loom put her finger on it, I think, when she wrote of Burnett's LOBF, "It was an actual STORY." The stories collected by the Provensens were "actual stories," too, while Andrew Lang's were not. They were just fairytales. What's the difference, though? I really can't say. Especially when I see that for so many people the fairytales were "actual stories," too.

ReplyDeleteSue Bursztynski, I wonder how much individuation among the oral tellings of the stories were lost when people like the Grimms wrote them down. Living in Norway and reading their fairytales last year, I found them a lot livelier than the Germanic version I'd read as a child.

~mwt

I envy your year in Norway, Megan! And perhaps you're right: an oral tale written down may be a bit like a butterfly pinned on a board, unless the person doing the pinning - the writing - can feel sufficiently easy to breathe a little of their own life into it? And I've always felt that Asbjornsen's tales are like listening to Asbjornsen, whereas the Grimm tales feel more archetypal and anonymous. But maybe that has lent them more power, in the end? I love them all, that's what it comes down to...

ReplyDelete