"The Book of Dreams and Ghosts" was written by Andrew Lang, famous for his many-coloured collections of fairy stories – The Red, The Blue, The Green Fairy Book and the others, which I borrowed one after another from the Ilkley Public Library when I was a child.

This is different. I came across a copy of the 1899 edition – by the way, don’t you just love an old book? – the smell, the rough, thick quality of the paper, the uneven edges, the gilt-embossed covers, the blackness of the print, and the almost tactile sense that so many other hands have held it and turned the pages? Anyway, I came across the 1899 edition some time ago in one of the passageways of my labyrinthine local second hand bookshop, and bought it at once for a couple of pounds.

And what it is, is pretty much what it says on the cover. A loose collection of supernatural or ghostly anecdotes taken from all kinds of sources: the key element being that none of them were originally offered as fiction. They are all, for what it’s worth, ‘true stories’. Most are contemporary; some are historical, but even the ones from old Icelandic sagas were intended to be read as factual accounts.

Andrew Lang has no axe to grind, no drum to bang. ‘The author has frequently been asked, both publicly and privately: “Do you believe in ghosts?” One can only answer: “How do you define a ghost?” I do believe, with all students of human nature, in hallucinations of one, or of several, or even of all the senses. But as to whether such hallucinations, among the sane, are ever caused by psychical influences from the minds of others, alive or dead, not communicated through the ordinary channels of sense, my mind is in a balance of doubt. It is a question of evidence.’

It has long seemed to me that there is a great difference between a ‘real’ ghost story and a fictional one. I used to live in a small Yorkshire village full of very old houses (the one I myself lived in dated in part from the late seventeenth century). The even older whitewashed farmhouse across the road, down by the beck, had a Red Lady who was sometimes spotted looking out of one of the small upstairs windows, and the farmer’s wife was used to hearing footsteps cross the floor overhead, when no one should be there. But that was it. There was no story attached. It was a pure phenomenon. Further down the road was a medieval ‘clapper bridge’ made of two huge stone slabs: this was known as ‘Monks Bridge’ probably because Fountains Abbey used to own much of the land: the cottage nearby was said to be haunted. Coming up the unlit road on foot one dark drizzly night at about two o’clock in the morning, I was disconcerted to see someone lingering by the ford, wearing what I took to be a cagoule. As I passed, the person – whoever it was – slowly and silently wandered down towards the edge of the stream. I didn’t think ‘ghost’; I thought ‘oddball’, and hurried on. Later, I wondered… And my own aunt was well known in the family for seeing the dead, including her husband, who once – pipe in hand – politely drew back to allow her to pass through a door in her Leeds Victorian terrace, some months after he had died.

The point about these stories is that there is no point. They have no real beginning, no middle, no end, no structure. They aren’t stories at all – just anecdotes. You hear them, you are impatient or fascinated according to your nature – and then you shrug, because there is no way to take them any further. People love explanations, of course, so sometimes you get embellishments which attempt to provide some kind of rationale: these often involve hidden treasure, wicked lords, seduced nuns, suicides and murders – and are rarely convincing. ‘Real’ ghost stories (and nearly everybody knows one) are open-ended oddities, and frequently the person involved does not even realise anything strange is happening until afterwards.

Here’s one example from Lang’s book:

The Dead Shopman

The brother of a friend of my own, a man of letters and wide erudition, was, as a boy, employed in a shop. The overseer was a dark, rather hectic-looking man, who died. Some months afterwards the boy was sent on an errand. He did his business, but, like a boy, returned by a longer and more interesting route. He stopped at a bookseller’s shop to stare at the books and pictures, and while doing so felt a kind of mental vagueness. It was just before his dinner hour and he may have been hungry. On resuming his way, he looked up and found the dead overseer beside him. He had no sense of surprise, and walked for some distance, conversing on ordinary topics with the appearance. He happened to notice such a minute detail as that the spectre’s boots were laced in an unusual way. At a crossing, something in the street attracted his attention; he looked away from his companion, and, on turning to resume their talk, saw no more of him.

In this account a number of details that, in a literary story, would require something to be made of them (the ‘dark and hectic’ features of the dead man: the curiously laced boots) are presented as mere corroborative evidence. This sort of ghost story is still very much alive and well in the oral tradition. “A funny thing happened…” “A friend of mine told me…” We enjoy listening; at least I do – but the teller is excused the structure of the literary ghost story. Because what happened is ‘real’, no other framework is necessary.

The least strained of traditional explanations for hauntings is that the spirit cannot rest until some wrong it did or suffered in life has been put right. Here’s another account from Lang’s book, verbatim from a seventeenth century book with the pleasing title: Pandaemonium, or the Devil’s Cloister Opened. Notice again the use of incidental details to lend verisimilitude:

About the month of November in the year 1682, in the parish of Spraiton, in the county of Devon, one Francis Fey (servant to Mr Philip Furze) being in a field near the dwelling place of his said master, there appeared to him the resemblance of an aged gentleman like his master’s father, with a pole or staff in his hand, resembling that he was wont to carry when living to kill the moles withal… The spectrum…bid him not to be afraid of him, but tell his master that several legacies which by his testament he had bequeathed were unpaid, naming ten shillings to one and ten shillings to another…

This being the sixteen hundreds, the restless spirit was considered of dubious origin – suspicions soon gratified by events. The ghost was joined by that of his second wife, and the neighbourhood was plagued with poltergeist activities which nowadays point to the aptly named Francis Fey himself as the source of the problems:

"Divers times the feet and legs of the young man have been so entangled about his neck that he has been loosed with great difficulty: sometimes they have been so twisted about the frames of chairs and stools that they have hardly been set at liberty."

But Fey’s master and neighbours pitied him as a victim of the simple malevolence of the devil, and no further explanation seemed to be required.

Lang’s book touches upon all kinds of occult anecdotes, from premonitory dreams (“mental telegraphy”) to the full blown and richly detailed ghost story of the ‘Hauntings At Fródá’ from Eyrbyggja Saga. Too long to retell here, the tale follows the disastrous series of events following the death of the strange Hebridean woman Thorgunna at the farm of Fródá on Snaefellness, when her hostess Thurid refuses to honour a deathbed promise to burn Thorgunna’s sumptuous bedhangings (which she had long coveted). It features one of the best and most matter-of-fact accounts ever of the ghost-as-reanimated-corpse – a phenomenon which Iceland does particularly well – and finishes on another splendidly Icelandic note (since that country is the real mother of parliaments) when the hosts of the dead are finally driven away by legal decision in a court of law.

This, though obviously ‘written up’ by the author of the saga, retains much of the loose-ended mystery of the oral tradition. We never find out much more about Thorgunna, or quite why the violation of the taboo laid on her bedhangings should have such drastic consequences.

I think maybe the very best literary ghost stories, such as those of MR James, manage to combine the best of both worlds – enough of a structure to provide a balanced, causal feel to the story, enough open-ended mystery to fascinate. A ghost story which is tied off too tightly isn’t really satisfying. They are very hard things to write well, and in my post for next week I’m going to talk about ghosts in children’s fiction. Oh, and here's a little competition. The four black and white illustrations in this post are from M.R. James' 'Ghost Stories of An Antiquary'. The first three people who can tell me, in correct order, which stories they match, will win a signed manuscript copy of my own ghost story "Danse Macabre".

To finish up with, here’s a ‘true’ ghost story which a friend told to me some years ago when I lived in France.

My friend was an American woman married to a Frenchman. They lived in a modern house in Fontainebleau, but her husband had elderly aunts who owned a chateau – one of those elegant small 18th century houses with shuttered windows and walled grounds that are scattered around the French countryside. This one was somewhere north of Paris, and from time to time the family would descend upon it for get-togethers at Christmas and Easter.

The bedrooms all had names, a charming custom – the Chambre Rouge, the Chambre Jaune, etc – but, said my friend, there was one bedroom everyone hoped they wouldn’t get, which latecomers would unavoidably be stuck with – the ‘Chambre des Mouches: ‘The Bedroom of the Flies.’

It wasn’t just, my friend said, that there always seemed to be flies in the room – big, sleepy, buzzy flies, crawling on the windows. One of the windows had been walled up, which was a little creepy. There was a small powder room off the main chamber, which may once have used as a nursery. But, mainly, you never got a good night’s sleep there. You lay awake and heard noises. As if something was moving about, or dragging across the floor. That was all. But she didn’t like it.

And so, when an American friend called Meredith was visiting from the States and a visit to the chateau was proposed, no one wanted to say anything when Meredith ended up getting the Chambre des Mouches. Because, really, it was probably all nonsense… but there was a certain interest around the breakfast table next morning when Meredith came downstairs.

“How did you sleep?”

Meredith hesitated. “I was comfortable enough, but I didn’t sleep so well. It was that darned cuckoo clock. It went off every hour, bing bong, cuckoo, cuckoo, and kept waking me up.”

“But Meredith,” said my friend gently, as an indrawn breath went around the table, “there isn’t any cuckoo clock.”

Monday, 26 April 2010

Tuesday, 20 April 2010

Riddles, Poems, Oracles

You remember, of course the riddle scene in ‘The Hobbit’, illustrated here by the amazing Alan Lee, where Bilbo Baggins pits his wits against hungry Gollum on the edge of the dark lake at the roots of the

Riddles have a long history, and probably a long prehistory too. There are riddles in the Bible, such as the one Samson baffled the Philistines with: ‘Out of the eater came something to eat/Out of the strong came something sweet’[3] (Judges 14,14) – still to be found, with its pictorial answer, on the green and gold tins of Tate and Lyle’s Golden Syrup. And one of the earliest known riddles, strikingly similar in form to Samson’s, is written on a Babylonian tablet and reads: ‘Who becomes pregnant without conceiving? Who becomes fat without eating?’[4]

(Oh, by the way, all the answers will be found at the bottom of this post. I’m certain you are going to try and guess them, so I’m not going to provide the answers straight up…)

Everyone remembers the riddle of the Sphinx, which Oedipus guessed; but did you know that Plato refers to children’s riddles in ‘The Republic’? (‘A man who was not a man threw a stone that was not a stone at a bird that was not a bird, on a twig that was not a twig’[5])’ Or that there are Sanskrit riddles in the Rig Veda and the Mahabharata? And what about the Norse riddles of the Elder Edda, such as ‘The Words of the All-wise’ in which the dwarf Alvis (literally ‘All-wise’) – anxious to win the hand of Thor’s daughter – answers a number of questions which might be called riddles in reverse:

Thor: What is heaven called, that all know

In all the worlds there are?

Alvis: Heaven by men, The Arch by gods,

Wind-weaver by vanes,

By giants High-earth, by elves Fair-roof,

By dwarves The Dripping Hall.

Thor: What is the moon called, that men see

In all the worlds there are?

Alvis: Moon by men, The Arch by gods,

The Whirling Wheel in Hel,

The Speeder by giants, The Bright One by dwarves,

By elves Tally-of-Years.

For verse after verse, Alvis provides the kennings – the riddling poetic descriptions – for all the elemental, important things in the world such as fire, rain, the moon and sun, the sea, forests, night and day (and beer)… until at last dawn breaks and he turns to stone.

When I talk to schoolchildren I usually ask them some Norse or Anglo-Saxon riddles, which of course are also poems: and it seems to me one of the best and easiest ways to show children what poetry is and why it might be fun to read. “So,” I say, “in a poem about the sea a Viking wouldn’t say ‘the sea.’ He’d call it the ‘whale’s home’ or the ‘swan’s bath’, and his audience would know what he meant. If you wanted to make a poem in which a king rewards one of his men with gold, you wouldn’t say ‘The king gave gold to his warrior.’ That would be plain boring. Instead you would have to say something like ‘The Land-Ruler gave Sif’s Hair to his Sword-Bearer.’

“For your listeners to understand it, they’d have to know the story of how the trickster god Loki cut off the goddess Sif’s beautiful hair. The other gods were so angry with him that he went to the dwarfs and got them to make Sif some beautiful new hair out of pure gold, which magically grew just like real hair.”

But there were plenty of other ‘kennings’ for gold. For example, you could call it ‘Frodi’s flour.’ And to understand that, your audience would remember a completely different story, about a Danish king called Frodi who bought two giant slaves and set them to turn two huge magic millstones which would grind out whatever you told them to grind. Instead of flour, King Frodi told them to grind out peace, prosperity and gold. (That’s why gold could be called ‘Frodi’s flour’.) For a time, King Frodi’s people enjoyed a golden age. Unfortunately, however, Frodi made the two giants work almost non-stop, not allowing them rest or sleep ‘for longer than it takes to hear a cuckoo call.’ In revenge, the two giants asked the millstones to grind out an army which attacked King Frodi and killed him. And that was the end of his peaceful reign.

The Vikings thought more of a man if he could weave words: some of their most renowned warriors were also poets, like Egil Skallagrimsson, and Grettir the Strong. The murderous Harald Silkenhair in my book ‘Troll Blood’ is a warrior poet from this tradition, and keeps his men happy by asking them riddles (here are two I made up for him):

“I know a stranger, a bright gold-giver

He strides in splendour over the world’s walls.

All day he hurries between two bonfires.

No man knows where he builds his bedchamber.”[6]

“I know another, high in the heavens

Two horns he wears on his hallowed head

A wandering wizard, a wild night-farer,

Sometimes he feasts, sometimes he fasts.”[7]

Spells, words, similes, riddles… the very word spell itself in Old Norse simply means speech. To describe the world is to apprehend it, to understand it. To this day we retain this double meaning. A magician may cast a spell, but children spell out words aloud, syllable by syllable. Words do not only give power, words are power. Even in the Judaeo-Christian sense: God creates the world with the words ‘Let there be light,’ and St John

Ursula K Le Guin made wonderful use of this in her Earthsea books, in which the language of wizards is literally the language of ‘the Making’: once you know the true name of a thing, you can summon it or reveal it: “the language dragons speak, and the language Segoy spoke who made the islands of the world…We call the foam on the sea sukien: that word is made from two words of the Old Speech, suk, feather, and inien, the sea. Feather of the sea, is foam. But you cannot charm the foam calling it sukien; you must use its own true name in the Old Speech, which is essa.”

‘Feather of the sea’: a kenning, a knowing – which is what ‘kenning’ means. Describing the foam is one way of knowing it better, of exploring its essence.

It seems to me that riddles may always have had dual purpose. They amuse us, but they do so in a different way from puns and jokes. If I ask you a riddle – even a simple child’s riddle like ‘What’s green and goes up and down?’[8] – and you can’t guess it, I score a point over you. More than that: I retain knowledge which I may or may not choose to tell you. I have the power to reveal or conceal. The riddle game is a contest which may once – as with Bilbo and Gollum, Thor and Alvis, Oedipus and the Sphinx – have had serious consequences.

The Delphic Oracle was traditionally delivered in obscure, riddling form. Today we may suspect that oracular utterances were made deliberately vague so as to be applicable to any variety of future events – but that seems to me false to the ancient way of thinking. Much more likely, the sibyl or seer regarded riddling, poetic speech as sacred: the authentic voice of God. Just as with poetry today, whoever heard it had to find their own meaning in what was uttered, follow the clue through the maze to the centre of themselves. Riddling speech, like poetry, may have been thought of as the truest, the most revelatory way of communicating.

Had I the heavens' embroidered cloths...

See how the floor of heaven's thick inlaid

With patines of bright gold...

Oh look at all the fire-folk sitting in the air!

The bright boroughs, the circle-citadels there!

Down in dim woods the diamond dells, the elves' eyes!

The grey lawns cold where gold, where quick-gold lies!”

To describe the night sky in this way is to use riddles as riddles were meant to be used. Can you still feel the shiver of power?

Friday, 16 April 2010

Old Manuscripts

(Imported from my post yesterday on the Awfully Big Blog Adventure)

What do you do with old manuscripts? I don’t mean crinkly old medieval manuscripts, I mean the manuscripts every writer owns, precious but useless piles of paper that represent months if not years of work – the forlorn not-dead-but-hardly-breathing remains of BOOKS THAT DID NOT MAKE IT. I have at least six.

I can’t bear to throw them out, yet there is absolutely zero chance of them ever being published. Not only were they never good enough, they’re a stage of me which I’ve outgrown, like an old chrysalis, and I couldn’t fit back in. On top of that, they’re too old-fashioned.

Take a look at this:

An electric bell began to ring, violently, without stopping. “Assembly!”

Another rush, this time for the classroom door. No teachers about yet. The corridor brimmed with people. Tall arrogant prefects and groups of scruffy-looking blazer-clad boys. First-form boys looking aggressive but clean, like choirboys playing rugger. The little girls were being pushed aside in the rush: Linda caught sight of a frightened face near the wall. Noise and laughter echoed like sounds in a swimming pool, saturating the corridor clad in its dirty cream paint and pock-marked notice boards.

The wide double doors to the hall were propped open: the flood surged in, slowed, broke into individuals who walked with more or less decorum to their places.

Coughing: shuffling. The slide of the khaki drugget underfoot. Herringbone pattern of woodblocks showing through a split seam. Mr Green, the music teacher, coming in talking over his shoulder to Miss Sykes: movement of interest among the girls. Mr Green was popular: he was married but rumoured to be in love with Miss Sykes, and it made the older girls jealous. He sat down at the organ, grinned at Mr Harvey who was up on the stage fixing hymn numbers, and made the organ groan breathily. Then he made it squeak. Laughter interrupted the general chatter.

The Head came in, wearing a black gown over his suit and banged for silence. He was smiling with a rather forced cheerfulness. The noise gradually faded into loud shushings from boys who knew the safe ways of being noisy. Precarious silence.

Yes, I wrote this – about thirty years ago. It’s not badly written, and it was then a fairly accurate representation of the beginning of a new term at a completely ordinary grammar school. Now – well, it’s just possible that some schools do still have blazers and prefects and electric bells, but I bet they’re not in the state sector; they won’t be holding quasi-religious assemblies for the whole school, the way it happened in my day; I don’t know when I last saw a ‘drugget’ (amazing word); and head teachers no longer wear gowns.

So, sadly, even in the unlikely case that I do decide to write a new story with a school setting, I can never use this passage. My personal memories and experiences of school are too out of date to be useful. (A lot of amateur writers don’t realise this, and rely upon distant memories and – worse still – recollections of the sort of books they themselves read as children, and waste their time producing manuscripts that seem dusty and old-fashioned. I’ve read manuscripts where it’s been quite obvious the only reason the action is set in 1975 is because that’s when the writer was a child. Unless there’s a valid plot-related reason to set your book in 1975, you had better not do so. )

All the same, I can’t bring myself to chuck the manuscript in the recycling. (It was called ‘The Outsiders’, Reader, and was a supernatural thriller about an unpopular girl who attracts – erm – the wrong sort of friends. The writing was good in parts, but the structure was a mess.)

Then there was the Alan Garner-y one about the children who meet a strange fugitive in the woods, who turns out to be on the run from the death-aspect of the Triple Moon Goddess (yes, her again) – and involved standing stones, unfriendly elves with golden faces, owls, ruins, and mazes. And there was one about the girl who finds her way through a picture into a magical jungle. I really loved this one for a few years, but looking at it now I see it’s appallingly overwritten. The jungle found its way into my prose, and you could choke to death on the descriptive writing. Only my mother could ever have had the patience to read it. No one else will ever want to do so, nor would I wish it – so why can’t I throw the thing out? Why? Why?

There they sit, taking up much-needed space in the drawer, too embarrassing and poorly written to re-read myself, but once so worked over, so dearly beloved! And so I ask again –

What do you do with old manuscripts? What do you do?

Monday, 12 April 2010

Cats In Books (or boxes)

As I honoured Polly the puppy, a few weeks ago, with her ‘own’ post about dogs in books, I thought I should extend the same honour to my long-suffering cats, currently and none-too-patiently ‘training’ Polly that YOU DO NOT CH

Cats appear much more frequently than dogs in modern children’s literature. I don’t know why this should be, but it is so. I’ll be discussing some of the more recent offerings later on in this piece, but let’s start with some oldies.

While Beatrix Potter wrote no books in which the main character is a dog, she wrote two entirely dedicated to the adventures of Tom Kitten – in the first, he is uncomfortably dressed up in that frilly blue suit and bursts all his buttons. In the second, ‘The Tale of Samuel Whiskers’, we memorably learn ‘how very unwise it is to go up a chimney in a very old house, where a person does not know his way, and where there are enormous rats.’

It’s a dark and exciting story which I loved as a child – and later lived in a similar house, in Yorkshire , where one of our cats did exactly the same thing. She went up the chimney and got lost in the flues. She emerged on the roof at one point (we heard her wailing) but it wasn’t till twenty-four hours later than she landed with a thump and a cloud of soot in my brother’s bedroom fireplace (no fire lit) at two o’clock in the morning. She was a black and white cat, the white parts normally snowy clean, but at that moment she was solidly black.

Anyway, cats in books. Does anyone else remember Barbara Sleigh’s ‘The Kingdom of Carbonel’? I just lapped up this series as a child. I don’t remember too much about them now, except that the roofs of the houses became, at night, a magical kingdom where Rosemary’s black cat Carbonel ruled and roamed. And then there was Ursula Moray Williams’ ‘Gobbolino the Witch’s Cat’: the story of a magical kitten who just wants to be an ordinary kitchen cat – despite the blue sparks that crackle from his fur. And – a writer now unaccountably neglected – Nicholas Stuart Gray’s magnificent cat narrator Tomlyn – outwardly cynical yet soft-hearted – in his retelling of the Rapunzel story, ‘The Stone Cage’.

Anyway, cats in books. Does anyone else remember Barbara Sleigh’s ‘The Kingdom of Carbonel’? I just lapped up this series as a child. I don’t remember too much about them now, except that the roofs of the houses became, at night, a magical kingdom where Rosemary’s black cat Carbonel ruled and roamed. And then there was Ursula Moray Williams’ ‘Gobbolino the Witch’s Cat’: the story of a magical kitten who just wants to be an ordinary kitchen cat – despite the blue sparks that crackle from his fur. And – a writer now unaccountably neglected – Nicholas Stuart Gray’s magnificent cat narrator Tomlyn – outwardly cynical yet soft-hearted – in his retelling of the Rapunzel story, ‘The Stone Cage’.

Another series I adored had no magic in it at all. I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who has read them, and they are long out of print, but Freda Hurt wrote a series of several excellent novels for seven to ten year olds about the effortlessly calm, collected and frighteningly brainy Mr Twink – a black cat with Siamese ancestry, who is the Sherlock Holmes of his little village, while his best friend the bluff retriever Sergeant Boffer takes on the role of Dr Watson.

Another series I adored had no magic in it at all. I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who has read them, and they are long out of print, but Freda Hurt wrote a series of several excellent novels for seven to ten year olds about the effortlessly calm, collected and frighteningly brainy Mr Twink – a black cat with Siamese ancestry, who is the Sherlock Holmes of his little village, while his best friend the bluff retriever Sergeant Boffer takes on the role of Dr Watson. (The author had a good understanding of the sort of friendship that can develop between and cat and a dog!) Between them, Twink and Boffer cope with any number of crises, from stolen bones (of the doggy variety), to kidnapped kittens, hysterical hens, and Red Tooth the (ratty) pirate. These were detailed, well observed, lovingly written and often very funny books – with a great cast of other village and farmyard animals too, including another memorable cat, the one-eyed Irish rascal Cap’n Jake.

But the classic cat book of the 20th century has to be Paul Gallico’s tear-jerking, tender, beautifully observed ‘Jennie’ – the story of a little boy called Peter who runs into the road, is hit by a car, and somehow is transformed into a cat. Terrified and lonely, he’s adopted by gallant little Jennie, a small and immensely lovable waif of a tabby cat, who teaches him how to behave like a real cat. (I love the description of the ‘leg-of mutton’ position where she’s trying to teach him how to wash!) As gradually Peter grows and learns, he becomes Jennie’s much needed protector – which makes it all the more of a wrench when he turns back into a boy…

Unlike dogs, there still seem to be plenty of cats prowling the pages of children’s fiction. Is it that the child-and-dog combination is less observable in contemporary life, and therefore isn't reflected in books, while cats have always been independent, operating in fiction without the need for a human side-kick? The modern tendency is to celebrate this independence by imagining a rich, even epic existence for fictional cats. No cosy village settings and domestic interiors; not even many witch’s cats – am I wrong? – but rainy cityscapes with adventurous felines slinking along wall-tops on desperate errands. Cats as mystics, cats as outlaws, cats as heroes, like SF Said’s ‘Varjak Paw’, Erin Hunter’s ‘Warrior Cats’ – and Inbali Iserles’ splendid ‘The Tygrine Cat’, published by Walker, which I read recently and thoroughly enjoyed. Like Paul Gallico, Iserles has a sharp and loving eye for the body language of cats:

Pressed down low to the ground, the soft fur of his belly almost stroking the tarmac, Mati slunk under people’s legs to investigate the market place.

Mati is the Tygrine Cat, a young ‘catling’ and exiled prince of a cat kingdom in far away Egypt

Although scarcely aware of the cold, Mati shivered. Blinded by the rain, he lurched over the tarmac, ran into a puddle, backed up, stumbled, kept going. For an instant, the market-place was illuminated by lightning. In that moment everything was white: market stalls, the boarded-up church, the rising pools of rainwater.

It’s a lovely, imaginative book with a sequel on the way.

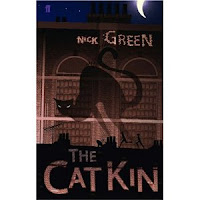

Another children's writer with an affinity for cats is Nick Green, whose book ‘The Cat Kin’ (and its sequel ‘Cats Paw’) takes the reader's identification with a cat hero to another level, and asks: What if a child could have a cat’s powers? How cool would it be, to be able to jump ten times your own height, see in the dark, tread silently, be almost invisible? What if you had a very unusual martial arts teacher who could show you how, via a forgotten ancient Egyptian skill called ‘pashki’? What a wonderful advantage your new powers would give you, if you had to combat a bunch of evil vivisectionists experimenting on animals in a nearby factory!

Here is Tiffany, chasing Ben through the treetops:

A tree bearing bobbly green fruits fanned its branches like the spokes of an umbrella. She bounded from spoke to spoke, catapulting herself off the last branch. In a blink she was inside a cathedral of a horse-chestnut, emerald light glimmering through leafy windows… Up she dashed through the rafters as if ascending a spiral staircase, leaping out through a portal in the leaves.

These are two brilliantly exciting books, the first originally published by Faber, but about to be reissued by Strident.

Unlike dogs, who appear in books to support humans, cats are lone heroes. A child will identify with the fictional child who owns a dog – and long for that companionship herself. But a child who reads a book about a cat will identify with the cat, and be out there stalking the rooftops, fighting the fights. Cats are adventurous yet cuddly, epic yet domestic. They seem so cool, so aloof, yet they purr so contentedly when sitting on your lap. Maybe Rudyard Kipling summed it up best in his story of 'The Cat WhoWalked By Himself' - the cat who manages to negotiate his place at the fire, attention from the Woman, and scraps from the meal, without ever having to compromise his treasured independence:

Saturday, 10 April 2010

Love songs for April

Walking through the fields with the puppy is just gorgeous in this sunny April weather. It's a physical relief to fill the lungs with warm air and see the flowers coming - the blackthorn white in the hedges - and hear the birds singing. And if it's so for us, who spend winter in centrally-heated houses, how much more so for the medieval people who celebrated spring in so many joyful poems?

I was thinking this morning about one of my favourites, and the way English has changed to the point where it's really not possible to quite do it justice with a modern translation...

"Bytuene Mershe ant Averil

When spray biginneth to spring,

The lutel foul hath hire wyl

On hyre lud to synge:

Ich libbe in love-longinge

For semlokest of alle thynge,

He may me blisse bringe,

Icham in hire bandoun.

An hendy hap ichabbe y-hent,

Ichot from hevene it is me sent,

From alle wymmen my love is lent

Ant lyht on Alisoun...

The first two verses mean, roughly,

"Between March and April

when leaf-sprays begin to spring,

the little bird(s)please themselves

by singing about their loves:

"I live in love-longing

for the loveliest of all things,

She may bring me bliss;

I am under her power."

But as for the chorus, those last four lines (which come at the end of each successive verse), my clumsy translation simply cannot convey the lilt and lift and the charm of them. With their dancing rhythm, they mean something like:

"But I have got the most wonderful luck,

I think it must have been sent from Heaven:

Among all the women in the world, my love

Has lit upon Alison."

'From alle wymmen my love is lent...' You can't translate it as 'I have forsaken all other women', since that implies that the lover could choose - whereas, what he is celebrating is his perfect helplessness in the matter. And this is why the lyric is so charming. He might have fallen in love with someone else: how lucky he is that he fell in love with Alison!

I say 'lyric', not just in the modern poetic sense, but in the modern musical sense: this poem was almost certainly intended to be sung. And so little have such things changed over the centuries, that I almost think the best translation might be these lines by George Gershwin:

I've got beginner's luck,

The first time that I'm in love

I'm in love with you.

Gosh I'm lucky!

I've got beginner's luck,

There never was such a smile

Or such eyes of blue.

Gosh I'm fortunate!

This thing we've begun

Is much more than a pasttime

For this time is the one

When the first time is the last time!

I've got beginner's luck

Lucky through and through

For the first time that I'm in love

I'm in love with you.

I was thinking this morning about one of my favourites, and the way English has changed to the point where it's really not possible to quite do it justice with a modern translation...

"Bytuene Mershe ant Averil

When spray biginneth to spring,

The lutel foul hath hire wyl

On hyre lud to synge:

Ich libbe in love-longinge

For semlokest of alle thynge,

He may me blisse bringe,

Icham in hire bandoun.

An hendy hap ichabbe y-hent,

Ichot from hevene it is me sent,

From alle wymmen my love is lent

Ant lyht on Alisoun...

The first two verses mean, roughly,

"Between March and April

when leaf-sprays begin to spring,

the little bird(s)please themselves

by singing about their loves:

"I live in love-longing

for the loveliest of all things,

She may bring me bliss;

I am under her power."

But as for the chorus, those last four lines (which come at the end of each successive verse), my clumsy translation simply cannot convey the lilt and lift and the charm of them. With their dancing rhythm, they mean something like:

"But I have got the most wonderful luck,

I think it must have been sent from Heaven:

Among all the women in the world, my love

Has lit upon Alison."

'From alle wymmen my love is lent...' You can't translate it as 'I have forsaken all other women', since that implies that the lover could choose - whereas, what he is celebrating is his perfect helplessness in the matter. And this is why the lyric is so charming. He might have fallen in love with someone else: how lucky he is that he fell in love with Alison!

I say 'lyric', not just in the modern poetic sense, but in the modern musical sense: this poem was almost certainly intended to be sung. And so little have such things changed over the centuries, that I almost think the best translation might be these lines by George Gershwin:

I've got beginner's luck,

The first time that I'm in love

I'm in love with you.

Gosh I'm lucky!

I've got beginner's luck,

There never was such a smile

Or such eyes of blue.

Gosh I'm fortunate!

This thing we've begun

Is much more than a pasttime

For this time is the one

When the first time is the last time!

I've got beginner's luck

Lucky through and through

For the first time that I'm in love

I'm in love with you.

Tuesday, 6 April 2010

Review and Interview: 'The Fool's Girl' by Celia Rees

It’s 1601, and Will Shakespeare, always on the scent of ideas for a new play, comes across a couple of brilliantly deft street performers. One is a fool called Feste, the other a young girl called Violetta. Intrigued, Will invites them to supper.

They were strangers, that much was clear, but more than that, there was a strangeness about them. A Fool who was no man’s fool, and his boy who was really a girl. He’d felt the old prickling sensation running through him. He’d sensed a story here, and he was seldom wrong.

It’s always exciting to see a new novel by Celia Rees: she’s one of those rare writers who are consistently excellent yet always surprising. In the recent past she’s written about female pirates and female highwaymen, (Pirates and Sovay) and Mayan prophecies and suicide cults (The Stone Testament).

Here she breaks more new ground: ‘The Fool’s Girl’ is a dark take on Shakespeare’s ‘Twelfth Night’. It’s told in a number of different voices, and begins with Violetta, Viola’s daughter, describing the sack of her city by Venetian and Uskok pirates led by none other than her own uncle Sebastian.

In some ways, the book is a fascinating extension of the play. Rees explores the currents of cruelty, melancholy and madness flowing under the play’s lyrical surface sparkle. It’s a writer’s business – a writer’s delight – to ask ‘what if…?’ and spin a story out of it. So Rees asks: what if Viola and Olivia, whose faux courtship is so central to the play, actually did prefer one another to their oh-so-suitable husbands? What if Viola’s twin brother Sebastian was jealous of his sister on two counts: for making a better marriage than himself and for stealing his wife Olivia’s affections? What if cross-gartered Malvolio harboured a furious and lasting grudge against the merry crew who tricked and abused him? What if the ending wasn’t happy-ever-after at all?

So Rees weaves a fast moving story in which Violetta has to flee Illyria with Feste the fool as her companion, and arrives in London London Illyria , and she’s going to need all the help Master Shakespeare can provide. In turn, as Will Shakespeare learns her history, he garners wonderful material for a new play – Twelfth Night – in which he will transform the iron and lead of real life into glittering gold.

I had to keep reminding myself as I read this book, that Rees’s characters, though so recognisably named, are not Shakespeare’s. In a switch-around that Shakespeare – who loved disguises, and boys playing girls playing boys – would surely have appreciated, what we have here is a novel masquerading as the real history behind the fictional Twelfth Night. Rees’s characters are harder, grittier, less lovable than Shakespeare’s. Feste, the Fool of the title, is particularly convincing:

The clown affected not to hear. He pulled a black tunic over his sweating body, his pale torso corded and knotted, his arms like twisted rope. He wiped his face with a rag, revealing a pale countenance almost as white as the paint that had covered it.

Rees’s Feste is a tough, wiry, commedia del Stratford

The world of ‘The Fool’s Girl’ is darker and more dangerous than the world of ‘Twelfth Night’: this is the ‘real’ historical England in which severed heads sit on spikes along London Bridge, while Sir Robert Cecil plays European power politics (and tries to make Shakespeare his pawn). At the same time there’s magic in the book, the sort of magic Elizabethans believed in: and hints of an older world, of the worship of Hecate, and of fairies in the Warwickshire woods. I just love the way Celia Rees uses all kinds of Shakespearean echoes. Sir Toby’s death is reminiscent of Falstaff’s. And recognise this?

‘There she is…’

Robin pointed towards the place where Violetta lay sleeping. She had found a shaded bank, fragrant with thyme and violets. She had meant to settle there to read while the lady tended her hives nearby, but the warmth of the sun, the scent of the flowers and the buzzing of the bees had sent her into reverie and then into sleep.

Surely this is the bank ‘whereon the wild thyme blows’ from ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’? Are the lord and lady really Oberon and Titania? Is Robin really Robin Goodfellow, or just a tinker’s child abandoned in the woods? Rees teases us with these questions – playing with our concepts of what is and isn’t real – as she suggests that in some way this fictional ‘reality’ is the raw material for Shakespeare’s plays.

Interview with Celia Rees:

You’ve always said you would never write about real historical figures – so what tempted you to break that rule and write about Shakespeare?

I had an idea… and that idea involved Shakespeare as a character. I’m always compelled by an initial idea and have to follow it, even if it means I have to break my own rules. Writers’ Rules are there to be broken, anyway, and the work is often better for it.

Shakespeare has made an appearance in a number of other children’s books, usually as a sympathetic, understanding character, but I felt what was different about your portrayal was the way you were able to hint at how it might actually have felt to be Shakespeare the writer. Did you draw from your own writing experience in order to do this?

At first, I found the prospect of writing about Shakespeare pretty scary and one of my ways to make him less daunting was to think of him as a writer – like me. There might be a bit of a difference in levels of talent but, I reasoned, there had to be some common ground. For example, that tingling feeling when you know you are on to an idea and the compulsion to follow it come what may. On a more mundane level, there is the business of juggling ‘real’ life and your writing life. Shakespeare must have had so many calls upon him, yet he still had to find the time and space and solitude to write. All writers know what that is like.

In recreating some of Shakespeare’s characters from ‘Twelfth Night’ did you have any pangs of regret – for example, at recasting Sir Andrew Aguecheek (‘I was adored once’) as Sir Andrew Agnew, a real villain?

Not really. I always found Sir Andrew a bit tedious and rather enjoyed turning him into a villain. The same with Malvolio. Our view of him in the play is partial – through the eyes of the ‘lesser people’ – very different from how Malvolio sees Malvolio. It was interesting to take him as seriously as he takes himself.

What made you decide on using a number of different voices as well as the authorial voice to tell the story – Violetta’s, Maria’s, Feste’s?

I always had it in my mind that the ‘survivors’ (Violetta, Feste and Maria) would tell Shakespeare about Illyria and what had happened there, so it made sense to tell that part of the story through their eyes, using their voices.

The world of ‘The Fool’s Girl’ is an unsafe and violent one. Did it come as a surprise to find your exploration of what is after all a comedy leading you into such dark places?

Twelfth Night is full of unsettling contrasts. It is set in sunny Illyria , but begins in the wind and the rain of Viola’s storm driven arrival and ends with the wind and the rain of Feste’s final song. For me, one of the fascinations of the play lies in its opalescent quality: it is as changeable as the taffeta that Feste recommends that the Duke should wear. Although the play is a comedy, one is never quite convinced by the dual wedding, the happy ending, because the whole thing is shot through with darker elements. The madness, the potential for violence, the fooling that goes too far are held in fine balance but, if Shakespeare had so chosen, they could easily have tipped over into tragedy.

Thanks so much, Celia! 'The Fool's Girl' is a lusciously produced hardcover published by Bloomsbury, £10.99

Friday, 2 April 2010

Stars and Primroses

This is such a happy time of year when in spite of cold winds and hailshowers, you know that spring is coming, and nothing can hold her back. I'm reminded of that triumphant Botticelli painting 'Primavera', and every joyful medieval lyric welcoming the spring - 'Lenten is come with love to town', and 'April with her showers sweet'. It seems to be a time for poetry, and I thought I'd show you one of my favourite books ever - handed to me over the garden fence by Mrs Cook our next-door neighbour, when I was probably about seven. I wonder if anyone else has a copy? It's called 'Stars and Primroses' and every page is illuminated. It taught me to love poetry (which previously I always skipped). I loved it to bits (almost literally) and the copy is still precious to me.

Here are some spring poems for you all, beginning with Housman's beautiful 'Loveliest of trees...' which for me perfectly captures the heartbreaking transience as well as the rapture of spring.

And perhaps my favourite, the deceptively simple

'Four Ducks on a Pond' by William Allingham.

Next week, I'm excited to be reviewing Celia Rees's new novel 'The Fool's Girl', set in the 1600's: a dark take on Shakepeare's 'Twelfth Night'. Celia has agreed to be interviewed, and I think her answers to my questions are going to be very interesting. That's for next Tuesday.

In the meantime, happy weekend, everyone! Happy Easter! Happy spring.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)