I’m thrilled to welcome Adèle Geras as the first of my guests on ‘Fairytale Reflections’. Adèle was born in Jerusalem

Adèle has loved fairytales all her life, especially the Hans Andersen stories and the Coloured Fairy books by Andrew Lang. Her most recent books ‘Troy Troy Carthage Troy

I’ve seen him somewhere before, she thought. He was making his way through the crowd to the beach, and it was his beard she recognized: a silvery-blue colour, as though glinting fish scales had been caught up in his hair. It fell almost to his waist. He seemed to be wet. His hair was streaming over his shoulders, and a powerful smell of fish came to Halie’s nose as he passed her. Some fisherman she’d seen once, but where? She turned to ask Theano whether she’d noticed him, but in the turning of her head, all memory of the man left her.

Ominous, understated, doomladen: Adèle can take an old story, tweak it, shake it inside out like a worn shirt, and – voilà – create a brand new garment. I love her books and perhaps especially her trilogy ‘Happy Ever After’ – a wonderfully fresh and unusual version of three classic fairytales, placed in a mid-twentieth century setting and seamlessly merging fantasy with realism. And so without more ado, here she is talking about:

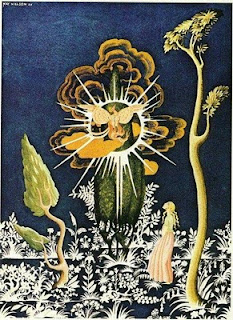

HANSEL AND GRETEL

I’m an only child. When I was a girl, I wanted siblings more than anything else. I put brothers and sisters into my fiction whenever I can because their interaction fascinates me. In one book, The Girls in the Velvet Frame, I used a photograph of my mother and four of her sisters (she had five and four brothers as well!) as the springboard for the story. So that’s the first thing that makes me like the tale: whatever might happen to them, Hansel and Gretel are TOGETHER. They help one another. They share everything. It’s not clear who’s the elder. In the Humperdinck opera, it seems Gretel is the one who teaches but it’s traditionally Hansel who suggests leaving the trail of breadcrumbs and so forth.

The premise, of parents wanting to rid themselves of their children, is horrendous. But in the context of the Hundred Years’ War and starvation and deprivation in much of Europe, there must have been thousands of desperate families with too many mouths to feed. Infanticide becomes more common when things are tough but these parents don’t commit murder with their own hands. Rather, they try and lose their children in the forest and hope for the worst.

So that’s where we start: with every child’s worst fear. They dread, we all dread, abandonment and the disappearance of the familiar. Whenever we hear about lost children, whenever we think of someone forcibly separated from their parents, our hearts shrink in horror. It’s a fear we can easily imagine.

So: two children lost in the dark wood. Alone, but for the help of a magical white bird. Birds are everywhere: they eat the crumbs and wreck any chance of finding the way home, and it’s a bird who leads them to the magical house of the Witch.

She’s not often portrayed as a traditional black hat and broomstick regulation witch. In the opera, she’s sometimes a grotesquely blown-up and exaggerated cake shop lady: too bosomy, too rouged, too feminine altogether. And she loves, loves, loves children. She loves to eat them. It reminds me of the Maurice Sendak phrase from Where the Wild Things Are: “We’ll eat you up, we love you so.” Sendak has said that this was uttered by his aunts and uncles when they pinched his chubby childish cheek in an excessively affectionate way and I can vouch for that kind of language from my own experience. My aunts and uncles, (see above) did just that: they’d pinch my cheek gently and exclaim in Yiddish: A zissaleh! Which means: A sweet little thing!

There we have it. The children’s real father and their stepmother don’t love Hansel and Gretel quite enough to keep the family together. The bad mother, the Witch, loves them so much she wants to consume them. To this end, she locks Hansel up and we have cages, and bones, and fattening him up like a calf. And for an extra nasty twist, we have the Witch turning Gretel into her servant while she’s preparing to feast on Hansel.

The end of the story is gruesome. Gretel tricks the Witch, who is reduced to ashes in her own oven. It’s not exactly bland fare for children. Hansel and Gretel escape and with the help of the White Bird, find their way home. They are carrying the Witch’s treasure with them, which doubtless guarantees them a better welcome than the one they might have expected.

Forests, birds, a witch, a marvellous house made of everything delicious, white pebbles gleaming in the moonlight, a cage, a chicken’s thigh bone, a treasure chest filled with jewels....all these are powerful ingredients but what makes Hansel and Gretel greater than the sum of its parts it the love that sees the brother and sister through the terrible ordeals they have to endure. That abides and it’s stronger than any enchantment you can throw at it.

PS I’m adding a poem here which I wrote years ago. It’s the Witch speaking.....

INVITATION

This time, be careful.

They have removed all the stones

That you used last time.

I have ironed sheets

and put green pears to blacken

on the bottom shelf

of the oven. Come

alone or with another.

That doesn't matter.

My mouth is open,

all my loose teeth are sharpened

and the cake is baked.

Let's pipe the icing

into red blobs like bloodstains

and call them flowers.

Pull the shutters closed.

We'll lick and suck the white hours

until you ripen.

Follow the thin bird.

Stay in those flapping shadows

and you will be bones.