Talking with a group of Girl Guides a while ago, we fell (as you

do) into a discussion about house spirits.

The best known example, annoyingly enough, is Dobby the house-elf from J.K.

Rowling’s Harry Potter series. I say

‘annoyingly’ because I have a soft spot for house spirits, and for me Dobby

isn’t the best ambassador for the breed. Rowling’s approach to magical creatures

from folklore is cavalier: she takes the names and happily reinvents the creatures. Her Boggart, for example, resembles not so much

the boggarts of folklore, but a nursery bogeyman. ‘Boggarts’, declares

Professor Lupin in ‘The Prisoner of Azkaban’, ‘like dark, enclosed spaces. Wardrobes, the gap beneath beds, the

cupboards under sinks. …So, the first question we must ask ourselves is, what is a Boggart?’ Of course Hermione comes up with the answer:

‘It’s a shape-shifter,” she said.

“It can take the shape of whatever it thinks will frighten us most.’

This certainly isn’t what a boggart from folk-lore does, although

they are sometimes able to take the shape of animals such as black dogs. More

about boggarts below. But to return to Dobby, the down-trodden house-elf of the

Malfoy family. Dobby is a slave. He lives

in terror, forced to punish himself whenever he criticizes his master. It’s a great twist of reinvention, but hardly

representative of house spirits in general. From English brownies, boggarts,

lobs and hobs, to the Welsh bwbach, from Scandinavian nisses and tomtes and German kobolds, to the Russian

domovoi, most house spirits are independent, mischievous, strong-minded

characters. And although Rowling employs the

folklore motif best known from the Grimms’ fairy tale ‘The Elves and the Shoemaker’ that a

gift of clothes will set the creature free (Dobby has to wear a pillowcase instead

of clothes), many folk-tales make it clear that far from longing for this gift,

many house spirits are perversely and deeply offended by it.

'It was indeed very easy to offend a brownie,' writes the folklorist Katherine Briggs in ‘A Dictionary

of Fairies’ (1976):

It was indeed very easy to offend

a brownie, and either drive him away or turn him from a brownie into a boggart,

in which the mischievous side of the hobgoblin was shown. The Brownie of

Cranshaws is a typical example of a brownie offended. An industrious brownie

once lived in Cranshaws in Berwickshire, where he saved the corn and thrashed

it until people began to take his services for granted and someone remarked

that the corn this year was not well mowed or piled up. The brownie heard him,

of course, and that night he was heard tramping in and out of the barn

muttering:

“It’s no weel mowed! It’s no weel

mowed!

Then it’s ne’er be mowed by me

again:

I’ll scatter it ower the Raven

stane

And they’ll hae some wark e’er

it’s mowed again.”

Sure enough, the whole harvest

was thrown over Raven Crag, about two miles away, and the Brownie of Cranshaws

never worked there again.

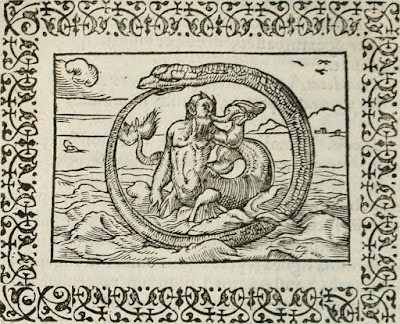

In folk-lore there’s never any suggestion that humans have a say in whether a brownie comes to work for them or not. Often they seem simply to belong in the house, to have been there for generations, such as the house spirit Belly Blin or Billy Blind in the illustration above, who comes to warn Burd Isabel that her betrothed, Young Bekie, is about to be forced to marry another woman.

‘Ohon,

alas!’ says Young Bekie,

|

‘I

know not what to dee;

|

For I

canno win to Burd Isbel,

|

An’

she kensnae to come to me.’

|

XIV

O it fell once upon a day |

Burd

Isbel fell asleep,

|

And up

it starts the Billy Blind,

|

And

stood at her bed-feet.

|

XV

‘O waken, waken, Burd Isbel, |

How

can you sleep so soun’,

|

Whan

this is Bekie’s wedding day,

|

An’

the marriage gaïn on?

|

Taking the hob's advice, Burd Isabel sets out with the Billy Blind as her helmsman, to cross the sea, find her lover and prevent the marriage. There's no great sense that she's surprised at this supernatural warning: rather, the Billy Blind (whose name like Puck's may have been generic, as it appears in other ballads too) seems to have been a known household inhabitant who could be expected to offer help when needed.

There is a tale of a hobthrust

who lived in a cave called Hobthrust Hall and used to leap from there to Carlow

Hill, a distance of half a mile. He worked for an innkeeper called Weighall for

a nightly wage of a large piece of bread and butter. One night his meal was not put out and he

left for ever.

Briggs, by the way, wrote her own story about a hobgoblin.

‘Hobberdy Dick’ (1955), set in 17th century Oxfordshire, is one of

the most delightful children’s books ever and glows with genuine folk-lore

magic. Here, Hobberdy Dick scampers up

to the Rollright Stones on May Eve, to greet his friends:

‘I’m main pleased to see ye,

Grim,’ said Dick, greeting with some respect a venerable hobgoblin from Stow

churchyard. ‘…These be cruel hard times. I never thought to see so few here on

May Eve; but ‘tis black times for stirring abroad now.’

‘Us

never thought the like would happen again,’ said Grim. ‘Since the old days when

the men in white came, and built the new church, and turned I out into the cold

yard, I’ve never seen its like for strange doings. First I thought old days had

come again, for they led the horses into the church in broad day; but the next

day they led them out again. …And then they broke the masonry and smashed up

the brave windows of frozen air… and these ten years there’s not been so much

as a hobby-horse nor a dancer in the town.’

The

Taynton Lob joined them – a small, good-natured creature with prick ears and

hair like a mole’s fur on his bullet head. ‘It may be quiet in Stow,’ he said,

‘but there’s more going on than I like in Taynton churchyard.’

‘What

sort?’ said Hobberdy Dick.

‘Women,’

said the Lob half-evasively, ‘and things that feed on ‘em, and counter-ways

pacing, and blacknesses.’

The Scandinavian Nisses are my personal favourites among

house spirits. The painting above is by the 18th century Danish painter Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard, and I was once contacted by a New York auction house who asked me to confirm that the subject is indeed a Nisse. As you can see, he wears a red cap and is sitting by the fireside with his broom, eating groute, or buckwheat porridge - but the women of the household are startled and uneasy in his presence. Where the painting is now I do not know, but hope the lucky owner will not object to my sharing the image, considering I lent a hand in identifying the subject. I first met Nisses in Thomas Keightley’s 1828 compendium ‘The

Fairy Mythology’, and made use of some of the legends in my own ‘Troll’ books

(now available, if you will excuse the quick puff, in one volume under the

title ‘West of the Moon’.) I was charmed

by their mischief, vanity, naïvety, their occasional bursts of temper and their

essential goodwill.

There lived a man at Thrysting,

in Jutland, who had a Nis in his barn.

This Nis used to attend to the cattle, and at night he would steal

fodder for them from the neighbours.

One

time, the farm boy went along with the Nis to Fugleriis to steal corn. The Nis

took as much as he thought he could well carry, but the boy was more covetous,

and said, ‘Oh, take more; sure we can rest now and then?’ ‘Rest!’ said the Nis; ‘rest! and what is

rest?’ ‘Do what I tell you,’ replied the boy; ‘take more, and we shall find

rest when we get out of this.’ The Nis then took more, and they went away with

it. But when they were come to the lands of Thrysting, the Nis grew tired, and

then the boy said to him, ‘Here now is rest,’ and they both sat down on the

side of a little hill. ‘If I had known,’ said the Nis as they were sitting

there, ‘if I had known that rest was so good, I’d have carried off all that was

in the barn.’

Here is my own Nis (in ‘Troll Fell’, book one of ‘West of

the Moon’) disturbing the sleep of young hero Peer Ulffson as he lies in the

hay of his uncles’ barn.

A strange sound crept into Peer’s

sleep. He dreamed of a hoarse little voice, panting and muttering to itself,

‘Up we go! Here we are!’ There was a scrabbling like rats in the rafters,

and a smell of porridge. Peer rolled over.

‘Up

we go,’ muttered the hoarse little voice again, and then more loudly, ‘Move

over, you great fat hen. Budge, I say!’

This was followed by a squawk.

One of the hens fell off the rafter and minced indignantly away to find

another perch. Peer screwed up his eyes and tried to focus. He could see nothing but black shapes and

shadows.

‘Aaah!’

A long sigh from overhead set his hair on end.

The smell of porridge was quite strong. There came a sound of lapping or

slurping. This went on for a few minutes. Peer listened, fascinated.

‘No

butter!’ the little voice said discontentedly. ‘No butter in me groute!’ It mumbled to itself in disappointment. ‘The

cheapskates, the skinflints, the hard-heared misers! But wait.

Maybe the butter’s at the bottom.

Let’s find out.’ The slurping began again. Next came a sucking sound, as if the person –

or whatever it was – had scraped the bowl with its fingers and was licking them

off. There was a silence.

‘No

butter,’ sulked the voice in deep displeasure. A wooden bowl dropped out of the

rafters straight on to Peer’s head.

|

| Our personal Nis, based on Abildgaard's, sits by our fire... |

In Russia, the house spirits are named domovoi, often given

the honorific titles of ‘master’ or ‘grandfather’. According to Elizabeth

Warner in ‘Russian Myths’ (British Library, 2002) the domovoi looked like a dwarfish old man,

bright-eyed and covered with hair, who dressed in peasant clothes and went

barefoot. ‘Sometimes he took on the shape of a cat or dog, frog, rat or other

animal. By and large, however, he remained invisible, his presence revealed

only by the sounds of rustling or scampering.’ Like nisses and brownies,

domovoi often busied themselves with household tasks, or with looking after

animals in the stables. Sometimes they

would befriend a particular cow or horse, which would flourish under their care. But they could also be mischievous, pinching

the humans black and blue at night, or throwing dishes and pans about like a

poltergeist. One last duty of the domovoi was to foretell ill events. ‘When a

family member was awakened in the middle of the night by the touch of a furry

hand that was cold and rough, some disaster was likely to occur.’

|

Temperamental, unpredictable, generous, hard-working,

sometimes dangerous, the house spirit is reminiscent of the household gods of

the Bible, the teraphim which Rachel stole from her father Laban (Genesis 31, 34), and of the

Lares and Penates of the Romans. Better

to have your own, humble little household spirit who could be pleased with a

dish of cream or a bowl of porridge, folk may well have thought, than to try

and gain the attention of the greater gods.

And so the house spirit became a member of the family, helping and

hindering in his own inimitable way.

Picture credits:

Brownie by Arthur Rackham

Billy Blind and Burd Isbel by Arthur Rackham Wikipedia

Lob Lie By the Fire by Dorothy P Lathrop: 'Down-a-down-derry,' Fairy Poems by Walter de la Mare 1922

Billy Blind and Burd Isbel by Arthur Rackham Wikipedia

Lob Lie By the Fire by Dorothy P Lathrop: 'Down-a-down-derry,' Fairy Poems by Walter de la Mare 1922

Nisse by Nicolai Abrahan Abilgaard

Domovoi by Ivan Bilibin - Wikimedia Commons

Lararium: shrine of household gods from Pompei: photo by Claus Ableiter - https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2673431