Monday, 24 September 2012

A Hobbity Weekend

As I'm sure you know, 'The Hobbit' was seventy-five on Friday last. Clearly, the only possible response was to hurry off to a Party of Special Magnificence. Which is why I found myself in London for an evening of celebratory readings and conversation at the British Library.

The speakers were the academic and writer Adam Roberts (author of the spoof 'The Soddit'); the ebullient and talented writer and broadcaster Brian Sibley, who created the BBC radio versions of The Hobbit and The Lord of The Rings; David Brawn of HarperCollins, who was there to show us many of Tolkien's own marvellous illustrations (published in a wonderful book called The Art of the Hobbit); and Jane Johnson, a Tolkien expert and lifelong enthusiast, who has also written the companion books to all the films.

The speakers were erudite and entertaining, the readings rich and marvellous, and the artwork haunting and evocative. I learned several things I'd never known (although I'm sure most Real Fans do) such as the fact that in the first edition of The Hobbit, Bilbo doesn't find the Ring; he merely wins it from Gollum as the prize for the Riddle Game - which must mean, unthinkable as it seems, that the famous line 'What has it got in its pocketses?' wasn't there in the first edition. (!) Apparently Tolkien revised the story for the second edition, having given further thought to the antiquity and significance of the Ring. And Adam Roberts further explained that in Unfinished Tales (which I confess I personally never have finished) Gandalf comes up with several suspiciously after-thought-like reasons for sending Bilbo on the journey to the Lonely Mountain: claiming it all to have been part of his deep plan to prevent the Necromancer (Sauron) in Dol Guldur from forming an alliance with Smaug and using the dragon as a terrible weapon for evil.

As Adam Roberts remarked, it rather defies belief that Gandalf seriously decided to recruit, from the other end of Middle Earth, a band of the most unlikely possible adventurers (staid little Bilbo, plus assorted rather unfit dwarves: think of Bombur) and send them through a myriad dangers to combat Smaug, when he might more simply have addressed himself to the valiant Men of Dale who were on the spot anyway. Far easier to believe that, in The Hobbit, Gandalf never had any such master plan, and the whole thing was the serendipitous caprice of a batty old wizard. But of such things is fiction made, and perhaps Gandalf/Tolkien can be forgiven a little bluffing on this occasion.

I thoroughly enjoyed the evening. But that was only the first part of my Hobbity Weekend. Because on Saturday, although I should have been cooped up in my office with the curtains drawn, tapping away at the keyboard writing my book, it was such a bee-yoo-tiful day I couldn't bear to, so D. and I went off with the dog to do one of our favourite walks around the Avebury stone circle: you start below the barrows on Overton Hill (which you'll agree look remarkably like the Barrow Downs), and walk a circular four or five miles along the chalky hillside, down to the Avenue, up between the stones to the circle, and then back via Silbury Hill.

It's very Tolkieny countryside... And of course, this was the weekend of the Autumnal Equinox, so Avebury circle was full of colourful modern pagans holding their rites. Rings of folk dressed in long robes and cloaks, holding staffs and beating drums, striking huge gongs, praising the land and the spirits of the land, the oak trees and the stones, and praying as people have always prayed everywhere and in all religions, for good to befall them and their neighbours: for richness of crops and richness of soul.

We sat on one of the benches outside The Red Lion pub, in the sunshine, with a drink and a couple of packets of crisps. It might as well have been The Prancing Pony. Everyone was happy, everyone was friendly. Lots of people admired the dog. (She's worth admiring.) Everyone - well, almost everyone - was in what you might call fancy dress. They had beaded ribands around their brows, or feathered hats on their heads; they carried musical instruments or carven staffs or baskets full of fruit and flowers; they sported tattoos and silver nose-rings, they wore bright colours: crimson or scarlet or white satin, yellow or purple. One had a wolfhound. On the way into the pub we quite definitely brushed past Aragorn (in his disguise as Strider): a young, lean, long-haired fellow in brown and green, with a broad, dull copper band encircling one brown wrist. You half expected people to start dancing the Springle Ring.

I didn't have a camera with me, and in any case it might have been rude to snap photos of people I didn't know, but it was, I assure you, quite lovely. Perfect strangers even chatted merrily in the loos.

We bought a little empty cut glass bottle from a small antique shop run by a charming elderly village couple. (Maybe it's not empty. Maybe it's filled with starlight. I haven't tried it out in dark places yet.) The old gentleman told us how he'd been born in Avebury, in a 16th century house just down the street, and how the Romans used to camp down by the river, and about all the Roman coins he'd found. The kind lady gave our Dalmatian Polly a long drink of water in a cut glass bowl. Polly, who had spurned the water in the pub's steel dog dish, lapped it all up thirstily and had seconds.

To add to the general fairytale feel, a large double-decker bus passing through the village had 'TROWBRIDGE' written as its destination. Yes, yes, it's the county town of Wiltshire, and probably the etymology has nothing whatever to do with trolls (aka trows) and billygoats, but on this particular day I thought it should, don't you? After that we walked around the circle and through the church yard, and back past mysterious Silbury Hill, the largest man-made mound in Europe, and up the chalk to the barrows, and got in the car and drove home, passing through Marlborough, a town which apart from the traffic looks as though the streets ought to be full of hobbits. Or if not hobbits, at the very least there should be dressed-up rabbits, and squirrels with shopping baskets on their arms.

Yes. At seventy-five, the Shire is alive and well.

Picture credits

The Hill: Hobbiton-across-the-Water, 1937. (MS. Tolkien drawings 26) Copyright the Tolkien Estate, reproduced here under the fair use clause of the copyright law.

The 'Hedgehog' Hill Barrows near Avebury: Wikimedia Commons, by Dickbauch

Part of Avebury stone circle and village, Wikimedia

The Red Lion, Avebury, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Immanuel_Giel

Katherine Langrish and Polly by Silbury Hill, copyright Katherine Langrish

High Street, Marlborough, Copyright Brian Robert Marshall and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Tumuli on Overton Hill near Avebury, Wiltshire: Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:UKgeofan

Friday, 21 September 2012

ON FAIRYTALES

by Terri Windling

I've been asked to reflect on fairy tales – which, as it happens, is something that I've been doing my entire professional life: thirty years of championing re-told fairy tales as a literary art form. I've reflected so long, and written so much, on the fairy tales that have meant the most to me that my difficulty now is in finding a new approach, a new pathway into this old, old territory. And so I'm going to start by telling you a story. It begins, of course, Once Upon a Time.

Once upon a time there was a girl who was forced to flee her childhood home. Why? Let’s never mind that now. Perhaps her parents were too poor to keep her. Perhaps her mother was an ogre or a witch. Perhaps her father had promised her to a troll, a tyrant, or a beast. She left home with the clothes on her back, and soon she was tired, hungry, and cold. As night fell, she took shelter in a desolate graveyard thick with nettles and briars. Beyond the graves was a humpbacked hill and in the side of the hill was a door. The girl walked towards the door and saw a golden key standing in its lock. She turned the key, opened the door, and crossed over the threshold….

I can still remember that moonlit night, but I don’t remember how old I was -- only that I was past the age when a girl should still believe in magic. Cold and quietly miserable in a childhood that seemed never-ending, I sat hunkered down in the grass among the gravestones of my grandfather’s church, trying to conjure a portal to a magic realm by sheer force of will. Like many children, I longed to discover a door to Faerie, a road to Oz, a wardrobe leading to Narnia, and I wanted to believe that if I wished with all my strength and all my will then surely a door would open for me. Surely they would let me in.

I wanted to flee unhappiness, yes, but there was more to my desire than this – more than just escape from the intolerability of Here and Now. My desire was also a spiritual one – for we often forget that spiritual quest is a common and natural part of childhood, as young people struggle to understand how they fit into the world around them. That night, my solemn conviction was that I did not fit into the world I knew, and so I sought to cross into some other world, through the power of imagination. Did I really think it might be possible? To tell the truth, I no longer know. But my longing for that door was real; and my sharp, physical, painful desire for the things I imagined lay just beyond: Vast, unmapped, unspoiled forests. Rivers that were clean and safe to drink. Wolves and bears who would guide my way once I’d learned the power of their speech. My childhood in the ordinary world was a transient, uprooted one; but beyond the door I’d find my place, my power, and my true home.

Like many children hungry for intimate connection with the spirit-filled unknown, what I failed to manifest that night I found in my favorite children’s books: in fairy tales, myths, and other tales of border-crossing and enchantment. I read these stories over and over. I devoured them and I needed them. But there came a time when I understood that I was growing too old for fairy stories, and I slipped them to the back of the shelves, embarrassed by my attachment to them. I was dutiful. I read “realistic” books about teen detectives, inventors, and spies; I read teen romances and girl-with-horse novels. I watched the wholesome Brady Bunch and the Partridge Family on television…and nowhere in the popular culture of the ‘60s did I see a life and a family that was remotely like mine. Secretly, I still preferred those fairy stories that I was meant to out-grow. I found a strange kind of comfort in them, though I couldn’t have told you why.

If only I’d known that in centuries past such stories weren’t labeled For Young Children Only, I wouldn’t have felt so obliged to hide these volumes behind Nancy Drew. I wish I'd known that magical tales had been loved by adults for thousands of years; and that in Europe the oldest known fairy tale collections had been published in adult editions, savored by the literary avante garde in 16th century Italy and 17th century France. Thanks to the work of contemporary fairy tale scholars we now know that early versions of familiar tales (Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, etc.) were sensual, dark, and morally complex. In the 16th century version of Sleeping Beauty, the princess is awakened not by a chaste, respectful kiss, but by the birth of twins after the prince has come, fornicated with her sleeping body, and left again (returning to a wife back home). In one of the oldest known versions of Snow White’s tale, a passing prince claims the girl's dead body and locks himself away with it, pronouncing himself in love with his beautiful “doll,” whom he intends to wed. (His mother, complaining of the dead girl's smell, is greatly relieved when her son’s macabre fiancé comes back to life.) In older versions of the Bluebeard narrative (such as Silvernose and Fitcher’s Bird), the heroine does not sit trembling while waiting for her brothers to rescue her – she outwits her captor, kills him, and restores the lives of her murdered predecessors. Cinderella doesn't sit weeping in the cinders while talking bluebirds flutter around her; she is a clever, angry, feisty girl who seeks her own salvation – with the help of advice from her dead mother’s ghost, not the twinkle of fairy magic.

It was not until the 19th century that volumes of fairy tales aimed specifically at children became the industry standard, supplanting the arch, sophisticated editions penned by authors of previous generations. Advances in cheap printing methods had created a hot new market in children’s books, and Victorian publishers sought products with which to tap into this lucrative trade. Ironically, the way was led by two scholarly German folklorists, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, editors of a German folk tale collection published for fellow academics. Upon realizing that a larger audience could be found among children and their parents, the Grimms revised their collection to make the tales more suitable for young readers, altering the stories more and more with each subsequent edition. The commercial success of the Grimms volume was noted by publishers in Germany and beyond, and soon there were numerous other fairy tale books aimed specifically at children -- filled with stories drawn from 16th, 17th, and 18th century fairy tale literature, now simplified and heavily revised to reflect Victorian “family values” and gender ideals.

As the next century dawned, the pendulum of adult literary fashion swung to tales of domestic realism while fairy tales and fantasy were increasingly left to the kids. Worse was to come as the century progressed, for Walt Disney would do more to turn fairy tales into pap than all of the Victorian fairy books put together as he rendered classic stories into animated films deemed suitable for American family viewing. Responding to criticism of the extensive changes he’d made in fairy tales like Snow White, Disney said: “It’s just that people now don’t want fairy stories the way they were written. They were too rough. In the end they’ll probably remember the story the way we film it anyway.”

Disney’s fairy tale films, and the imitative books they spawned, went a long way to foster the modern misconception that fairy tales are children’s stories and have always and only been children’s stories. Yet fairy tales, J.R.R. Tolkien pointed out (in his lecture “On Fairy-stories,” 1938) have no particular historical association with children; they’d been pushed into the nursery like furniture the adults no longer want and no longer care if its misused. “Fairy–stories banished in this way,” he said, “cut off from a full adult art, would in the end be ruined; indeed, in so far as they have been so banished, they have been ruined."

Professor Tolkien himself deserves much of the credit for bringing magical tales back to an adult audience, which he did, of course, through the international success of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien’s books surprised critics by striking a chord with readers of all ages and from all walks of life, directly challenging the assumption that fantasy had no place on adult bookshelves. Today, a generation of readers who have grown up with Bilbo and Frodo Baggins – not to mention Sparrowhawk, Harry Potter, Lyra Belacqua, and the whole modern fantasy publishing genre – may not fully comprehend the boundary-busting nature of Professor Tolkien’s achievement.

In the place and time where I grew up, for example, there were only a very few fantasy books available in the local library (the Narnia books, the Oz books, The Wind in the Willows, a handful of others ), strictly confined to the children’s section – and somewhat suspect even there. Fantasy, I understood, was like the training wheels on my first two-wheel bike: a forgivable crutch at the outset, but one I was meant to progress beyond needing. I hadn’t progressed. I still craved such tales, though they stood on shelves meant for much younger kids. A worried librarian actually took The Blue Fairy Book out of my check-out stack, replacing it with a more “age appropriate” (and insipid) story about a perky camp counselor. The message was clear: fantasy belonged to the children who still played with dress-up dolls, and my craving for it led me to think there was something wrong with me. It was only later that I learned that others shared this craving, including adults. “I desired dragons with a profound desire,” wrote J.R.R. Tolkien of his own adolescence. “Of course, I in my timid body did not wish to have them in the neighborhood…. But the world that contained even the imagination of Fáfnir was richer and more beautiful, at whatever the cost of peril.”

It wasn’t until I turned fourteen that I discovered Tolkien’s trilogy, although the books had been available in American editions for some years before that. I began The Fellowship of the Ring on the school bus on a grey winter morning, reading with pure amazement as Middle Earth opened up before me. Here, in the language of fantasy, was a story that seemed more real to me than any “realistic” story I knew -- a story about danger, terror, and courage; about the cost of heroism and the importance of moral choices. In Middle Earth, as in my parents' house, an epic battle between good and evil was waging, and even a humble, seemingly-powerless creature like a hobbit could affect its outcome.

Some months after The Lord of the Rings, I discovered Tolkien’s slim volume 'Leaf by Niggle' containing his lecture/essay “On-Fairy Stories” – which was, for me, a more influential text than all the good professor’s celebrated fiction. It was here I first learned that fairy tales had an old and a noble lineage -- and that they’d once been more, so much more, than the Disney versions known today. I dug out my favorite fairy tale books and I read the old tales with new eyes; and this time I understood why I’d clung to these stories for so many years. Like Tolkien’s books, they addressed large subjects: good and evil, cowardice and courage, hope and despair, peril and salvation – all subjects not unfamiliar to children raised in embattled households. Fairy tales spoke, in their metaphorical language, of danger, struggle, calamity – and also of healing journeys, self-transformation, deliverance, and grace. The fairy tales that I loved best (Donkeyskin, The Wild Swans, The Handless Maiden) were variations on one archetypal theme: a young girl beset by grave difficulties sets off, alone, through the deep, dark woods. Armed with quick wits, clear sight, persistence, courage, compassion, and a dollop of luck, she meets every challenge, solves every riddle, and transforms herself and her fate. This was my story, my myth, the central text and theme of my young life’s journey. This was the story I needed to hear again and again and again.

There is irony in the fact that the door I’d been looking for that night among the graves had been right in front of me all along, in the pages of those old fairy tale books. But I’d needed Tolkien’s lecture to understand what it was I loved about fairy tales; his words were the golden key that finally opened the door for me. I then crossed the threshold into the land of Story, where I have been travelling ever since: wandering its vast forests, drinking from its clear, cold streams, learning to speak with wolves and bears (which, as it turns out, is not half as hard as you would think).

If I could have one Magic Wish today, I would like to travel back in time and to find that miserable girl among the graves, appearing before her like a classic Good Fairy, draperies flapping in the wind behind me. This is what I would like to tell her (and, indeed, every other child just like her): “There are better worlds out there, my dear. And I promise you, you're going to find them.”

Terri Windling is an American writer, artist and editor of fantasy for

children and adults. She has won more awards than you can shake a stick

at: you can look it all up on Wikipedia, here. A world of brilliant fantasy opens up from a reading of some of the many

anthologies she has edited, such as ‘The Armless Maiden and other

Tales for Childhood’s Survivors’, a collection of powerful stories about

‘the darker passages of childhood’; and, with Ellen Datlow, many

wonderful myth and fairytale-inspired anthologies for young adults such

as ‘The Green Man’ and ‘The Faery Reel’.

Picture credits:

From 'East of the Sun' by Kay Nielsen

'Fafnir' by Arthur Rackham

'Faerie Folk' by Arthur Rackham, 1914, frontispiece, Imagina by Julia Ellsworth Ford, New York: Duffield & Company. Picture found at blog: 'Art of Narrative'

Tuesday, 18 September 2012

Folklore Snippets: The Troll who built a Church

Esbern Snare, 1127 to 1204, was a daring Danish nobleman and

commander who, around 1170, fortified the

town of Kalundborg,

Zealand, with a castle and towers, and also

set about building a rather wonderful five-towered church which still exists.

Here it is!

But the story goes that Esbern had supernatural help. Here is the account, from Thomas Keightley’s

Fairy Mythology:

When Esbern Snare was about building a church in Kalundborg,

he saw clearly that his means were not adequate to the task. But a Troll came to him and offered his

services; and Esbern Snare made an agreement with him on these conditions, that

he should be able to tell the Troll’s name when the church was finished; or in

case he could not, that he should give him his heart and his eyes.

The work now went on rapidly, and the Troll set the church

on stone pillars; but when all was nearly done, and there was only half a

pillar wanting in the church, Esbern began to get frightened, for the name of

the Troll was yet unknown to him.

One day he was going about the fields all alone, and in

great anxiety on account of the perilous state he was in; when, tired and

depressed, by reason of his exceeding grief and affliction, he laid him down on

Ulshöi bank to rest himself a while.

While he was lying there, he heard a Troll-woman within the hill saying

these words:

Tie stille, barn min!

Imorgan komme Fin,

Fa’er din,

Og gi’er dig Esbern

Snares öine og hjerte at lege med.

Lie still, baby mine!

To-morrow cometh Fin,

Father thine,

And giveth thee Esbern

Snare’s eyes and heart to play with.

When Esbern heard this, he recovered his spirits and went

back to the church. The Troll was just

then coming with the half-pillar that was wanting for the church; but when

Esbern saw him, he hailed him by his name and called him “Fin.” The Troll was so enraged by this, that he

went off with the half-pillar through the air, and this is the reason that the

church has but three pillars and a half.

(However, as Keightley adds in a footnote that ‘Mr Thiele saw

four pillars in the church’ - the four granite columns supporting the central

tower - and that ‘the same story is told of the cathedral of Lund in Funen’,

and anyway the tale is clearly a variant of Rumplestiltskin and Tom Tit Tot –

then perhaps this story isn’t true after all…)

Picture credit: The church "Vor Frue Kirke" in the town Kalundborg. The town is located in West Zealand, Denmark. Photo by Hubertus, Wikimedia Commons, 14 April 2010

Friday, 14 September 2012

"The Provenson Book of Fairytales" (with scary pictures)

by Megan Whalen Turner

When Katherine asked if I might like to write a blog post about my favorite fairy tale, I drew a blank. I’m almost afraid to admit this, but I didn’t like fairy tales when I was a kid. I thought they were dry, their characters two dimensional and their plots predictable. But as I wrote my e-mail, meaning to decline, one particular book did come to mind. It was Alice and Martin Provensen’s book of fairy tales, and I remembered it mainly for the illustrations, which were terrifying.

I asked Katherine if that sort of subject would do for a non-fairy tale reader and she said, yes. So . . .

This book sat on my shelf untouched for years. Too disturbing to read, too compelling to overlook, it was a gift and absolutely could not be sent off to the library book sale. No matter how many times I weeded my collection, it always remained. There on the shelf, with its dark mesmerizing illustrations in black and purple and virulent green.

Those of you familiar with the deeply charming Animals of Maple Hill Farm, or with A Visit to William Blake's Inn which won both the Newbery Award and a Caldecott Honor in 1982 might be surprised that anything by the Provensens could be that disturbing.

Yes, well they were always about more than cats and bunnies and talking sunflowers. In The Animals of Maple Hill Farm the Provensens introduce you to all the hens and roosters at their farm in a two page spread that includes examples of the obnoxious rooster, Big Shot, being nasty to the other roosters and bullying the hens, and then Big Shot gets carried off by a fox.

And no one minds, they say with a shrug.

Look through A Visit to William Blake’s Inn and notice the semi-circular smile on the Man in the Marmalade Hat. That's him on the left.

Observe his chiclet style teeth. Imagine an entire book peopled with those smiles and those teeth, and no friendly anthropomorphic sunflowers, either. The best you get is some malevolent looking mice.

A mouse from "The Forest Bride" by Parker Filmore.

This from the story “The Lost Half Hour” by Henry Beston:

Or this from “Beauty and the Beast” by Arthur Rackham:

I couldn’t fit this into one scan, but if you look carefully you can piece together the composition with Beauty sitting at the table and the Beast lurking just around the corner. The Provensens have used the gutter between the pages to emphasize the corner in the image. The images aren’t merely frightening, they are brilliant and frightening. The hands of the beast are huge and clawed, yet they hang awkwardly, giving you the idea that in an unfortunate fumbling manner they might accidentally rip your arm off.

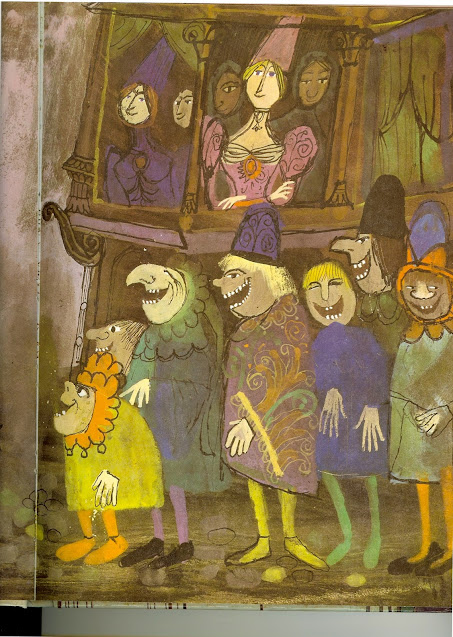

This is from the happy, upbeat (not), The Prince and the Goose Girl by Elinor Mordaunt.

Holy Cow. This book gave me the heebie-jeebies.

So, of course, I left it on the shelf when I grew up and moved out on my own. And I never read it when I visited home. No, never. And when I saw a copy at a thrift store, of course I said, “Oh, look!” And bought it instantly.

Okay, so there . . . there may be a contradiction there. And when I said the book sat on my shelf untouched? I lied. When I got the book home and looked through it, I remembered every single story. "The Lost Half Hour" where poor unfortunate Bobo is sent out by the Princess to find the half hour lost while she overslept. “Feather O’ My Wing” by Seamus McManus with the same spiteful stepsisters as “Beauty and the Beast,” but a story line a little more like “East of the Sun, West of the Moon.” Barbara Leonie Picard’s "Three Wishes" were the peasant boy gives away his hard earned wishes and receives them all back again.

And perhaps my favorite, “The Prince and the Goose Girl.” The heroine Erith is absolutely indomitable. She won’t back down, not even if it costs her life, and when the Prince realizes this he also realized that Erith is right that he isn’t much of Prince. Fortunately, he becomes a reformed man, and because Erith is as kind as she is brave, it all works out in the end.

Why, oh, why didn’t I think of "The Prince and the Goose Girl" when Katherine asked me to write a post?

I think the answer has something to do with the Introduction to the book, which may be the one part I really didn’t read. In the introduction Joan Bodger explains that these are literary fairy tales. The italics are hers, not mine and their elitism makes me uncomfortable, but I think Bodger is saying the same thing that I am struggling with. I didn’t like fairy tales when I was growing up because most of the things that were labeled “Fairy Tales” in my experience were those bowdlerized, dessicated versions that were three paragraphs long and came in books of a hundred or more and had absolutely no personality. Everything that gave them depth had been sifted out because it was rude, or it was frightening, or it made the story too long for its intended audience.

They were stripped down to their Propp’s morphology. I tend to think of them as skeletons of stories, but the Provensons remind me that they aren’t dead skeletons so much as a seed bank that any of us can draw on, and that when we do draw on this seed bank, what we are writing (with or without the upscale qualifier literary) is fairy tales.

Gen is truly an unreliable narrator – an infuriating, intelligent, secretive, multi-layered individual whom you get to like very much indeed. The book is set in an almost but-not-quite familiar early Mediterranean world, where gods are worshipped who resemble the Greek pantheon but are not – and where small city states war against one another, or form alliances, under the shadow of a powerful Eastern empire. 'The Thief' was followed by its sequels, ‘The Queen of Attolia’, ‘The King of Attolia’, and ‘A Conspiracy of Kings’ and from an impressive start they just get better and better. Beautiful writing. Lots of devious politics. Lots of twists. Unforgettable characters. I'm a huge fan, and I'm hoping there's going to be more...

When Katherine asked if I might like to write a blog post about my favorite fairy tale, I drew a blank. I’m almost afraid to admit this, but I didn’t like fairy tales when I was a kid. I thought they were dry, their characters two dimensional and their plots predictable. But as I wrote my e-mail, meaning to decline, one particular book did come to mind. It was Alice and Martin Provensen’s book of fairy tales, and I remembered it mainly for the illustrations, which were terrifying.

I asked Katherine if that sort of subject would do for a non-fairy tale reader and she said, yes. So . . .

This book sat on my shelf untouched for years. Too disturbing to read, too compelling to overlook, it was a gift and absolutely could not be sent off to the library book sale. No matter how many times I weeded my collection, it always remained. There on the shelf, with its dark mesmerizing illustrations in black and purple and virulent green.

Those of you familiar with the deeply charming Animals of Maple Hill Farm, or with A Visit to William Blake's Inn which won both the Newbery Award and a Caldecott Honor in 1982 might be surprised that anything by the Provensens could be that disturbing.

Yes, well they were always about more than cats and bunnies and talking sunflowers. In The Animals of Maple Hill Farm the Provensens introduce you to all the hens and roosters at their farm in a two page spread that includes examples of the obnoxious rooster, Big Shot, being nasty to the other roosters and bullying the hens, and then Big Shot gets carried off by a fox.

And no one minds, they say with a shrug.

Look through A Visit to William Blake’s Inn and notice the semi-circular smile on the Man in the Marmalade Hat. That's him on the left.

Observe his chiclet style teeth. Imagine an entire book peopled with those smiles and those teeth, and no friendly anthropomorphic sunflowers, either. The best you get is some malevolent looking mice.

A mouse from "The Forest Bride" by Parker Filmore.

This from the story “The Lost Half Hour” by Henry Beston:

Or this from “Beauty and the Beast” by Arthur Rackham:

I couldn’t fit this into one scan, but if you look carefully you can piece together the composition with Beauty sitting at the table and the Beast lurking just around the corner. The Provensens have used the gutter between the pages to emphasize the corner in the image. The images aren’t merely frightening, they are brilliant and frightening. The hands of the beast are huge and clawed, yet they hang awkwardly, giving you the idea that in an unfortunate fumbling manner they might accidentally rip your arm off.

This is from the happy, upbeat (not), The Prince and the Goose Girl by Elinor Mordaunt.

Holy Cow. This book gave me the heebie-jeebies.

So, of course, I left it on the shelf when I grew up and moved out on my own. And I never read it when I visited home. No, never. And when I saw a copy at a thrift store, of course I said, “Oh, look!” And bought it instantly.

Okay, so there . . . there may be a contradiction there. And when I said the book sat on my shelf untouched? I lied. When I got the book home and looked through it, I remembered every single story. "The Lost Half Hour" where poor unfortunate Bobo is sent out by the Princess to find the half hour lost while she overslept. “Feather O’ My Wing” by Seamus McManus with the same spiteful stepsisters as “Beauty and the Beast,” but a story line a little more like “East of the Sun, West of the Moon.” Barbara Leonie Picard’s "Three Wishes" were the peasant boy gives away his hard earned wishes and receives them all back again.

And perhaps my favorite, “The Prince and the Goose Girl.” The heroine Erith is absolutely indomitable. She won’t back down, not even if it costs her life, and when the Prince realizes this he also realized that Erith is right that he isn’t much of Prince. Fortunately, he becomes a reformed man, and because Erith is as kind as she is brave, it all works out in the end.

Why, oh, why didn’t I think of "The Prince and the Goose Girl" when Katherine asked me to write a post?

I think the answer has something to do with the Introduction to the book, which may be the one part I really didn’t read. In the introduction Joan Bodger explains that these are literary fairy tales. The italics are hers, not mine and their elitism makes me uncomfortable, but I think Bodger is saying the same thing that I am struggling with. I didn’t like fairy tales when I was growing up because most of the things that were labeled “Fairy Tales” in my experience were those bowdlerized, dessicated versions that were three paragraphs long and came in books of a hundred or more and had absolutely no personality. Everything that gave them depth had been sifted out because it was rude, or it was frightening, or it made the story too long for its intended audience.

They were stripped down to their Propp’s morphology. I tend to think of them as skeletons of stories, but the Provensons remind me that they aren’t dead skeletons so much as a seed bank that any of us can draw on, and that when we do draw on this seed bank, what we are writing (with or without the upscale qualifier literary) is fairy tales.

Note from Katherine:

It's an honour to have Megan on the blog. In about 1998 I was living in America, in upstate New York, and one of the bolt-holes

for me and my two young daughters was the local Barnes and Noble

(conveniently close to Toys R Us and a miniature horse ranch). Trawling

the shelves one day - for myself, of course; the girls were in the

littlies section - I pulled out a book called 'The Thief' by Megan Whalen Turner.

It was a Newbery Honor book – I flicked it open and read a snippet –

and thus met her narrator Gen (short for Eugenides), who is languishing

in prison, loaded with chains, because:

...I had bragged without shame about my skills in every wine shop in the city. I had wanted everyone to know that I was the finest thief since mortal men were made…

...I had bragged without shame about my skills in every wine shop in the city. I had wanted everyone to know that I was the finest thief since mortal men were made…

Gen is truly an unreliable narrator – an infuriating, intelligent, secretive, multi-layered individual whom you get to like very much indeed. The book is set in an almost but-not-quite familiar early Mediterranean world, where gods are worshipped who resemble the Greek pantheon but are not – and where small city states war against one another, or form alliances, under the shadow of a powerful Eastern empire. 'The Thief' was followed by its sequels, ‘The Queen of Attolia’, ‘The King of Attolia’, and ‘A Conspiracy of Kings’ and from an impressive start they just get better and better. Beautiful writing. Lots of devious politics. Lots of twists. Unforgettable characters. I'm a huge fan, and I'm hoping there's going to be more...

Tuesday, 11 September 2012

RAVEN HEARTS by Fiona Dunbar

Now here comes Raven Hearts, the fourth in her series about the irrepressible Kitty Slade, whose ability to see ghosts

(a talent called phantorama, inherited from her dead Greek mother) leads her into all sorts of adventures. Kitty is a determined and attractive heroine, who takes her uncomfortable gift firmly in her stride. The first in the series, Divine Freaks, featured a dodgy London landlord, a

scalpel-wielding ghost in the school biology lab, a back-street

taxidermist, shrunken heads, and a fraudulent antiques business. In the sequel, Fire and Roses Kitty deals with a poltergeist, and encounters the ghost of a member of the Hellfire Club (you can find Fiona's post about her research for this book here); while the third book,Venus Rocks, is set in Cornwall and includes a ghost ship and evil Cornish sprites called spriggans. From which you'll gather that a strong sense of place is one of the keynotes of these books.

So I was more than excited to read Raven Hearts, especially as it's set in Yorkshire on Ilkley Moor, where I spent much of my own childhood scrambling about wishing I could have adventures like Enid Blyton's Famous Five, although if I'd found as much excitement as Kitty does, I would undoubtedly have chickened out and decided reading about adventures was better than experiencing them, after all.

|

| The Cow and Calf Rocks |

Arriving in her family's camper van 'The Hippo' at a campsite near Ilkley Moor, Kitty rapidly becomes aware that all is not well. People have gone missing on the moor, which is rumoured to be haunted by a spectral black dog called the Barghest. (A nice Yorkshire folklore touch, that: Brontë devotees may remember Jane Eyre imagining the Barghest just before she meets Mr Rochester for the first time...) At the famous Cow and Calf Rocks Kitty meets a ghostly woman searching for her lost son. She hears childrens' voices chanting an eerie song (and yes, it's 'Ilkla Moor Baht'At', which when you think about is a pretty gruesome little ditty: 'the worms'll coom an' ate thee oop', etc.) She's haunted by ravens. And when she meets a highly unreliable spirit called Lupa, Kitty really does find herself in deadly danger...

I learned something while reading this book. I grew up knowing about the prehistoric Swastika Stone, the Roman baths at White Wells, and the massive Cow and Calf Rocks. But how come I'd never heard of the stone circle called the Twelve Apostles? Fiona Dunbar uses these settings deftly to create a sense of mystery; the story moves at a cracking pace, and by the time Kitty is cycling alone over the moor as dark falls and the moon rises, the stage is perfectly set for the appearance of something awful...

The Kitty Slade books are expertly pitched for the 9 + reader who wants something scary and exciting, but not TOO scary. One of the things I like most about them is that her heroine has back-up. Kitty can rely on her brother and sister

for help, while her Greek grandmother Maro is a reassuring if

eccentric presence. This helps steady the reader’s nerves through some

of the more hair-raising passages. If you have a nine-to-thirteen year old in your life with a taste for mystery, ghosts, adventure and a (light) touch of horror, believe me, they're going to really, really enjoy this series.

RAVEN HEARTS by Fiona Dunbar, Orchard

Picture credits:

Cow and Calf, wikimedia commons, Hugh Chappell

RAVEN HEARTS by Fiona Dunbar, Orchard

Picture credits:

Cow and Calf, wikimedia commons, Hugh Chappell

Friday, 7 September 2012

On Bedtime Stories

When my daughters were small I used to read aloud to them

every evening, just as my mother used to read to me, and her mother to her, I

dare say…generation before generation.

It’s something I miss, now they’re all grown up. No matter what sort of day you’ve had, how

cross and tired you may be, there’s something lovely about snuggling up with

your children on the sofa, or on the edge of one of their beds (strictly

alternating between younger daughter’s bedroom and older daughter’s bedroom:

‘it’s my turn tonight!’), and reading

a book chapter by chapter.

Since they were keen readers anyway, I used to choose books

to read aloud which I thought they might not actually pick for themselves. So instead of contemporary fiction I chose

older books, things I’d loved as a child, books which might develop slowly, in

that leisurely, let’s-take-time-over-the-first-chapter way which we’re not

allowed to write any more, since children’s attention spans are now supposedly

so short. Well, children love to be read

to, and they rarely get bored while they’re cosied up next to you, the centre

of your attention, listening to a lovely story competently read. It’s

completely different from struggling along by themselves. Reading aloud is just

a huge pleasure all round.

And so together we read all sort of classics. The Treasure Seekers, The Wouldbegoods, The

Hobbit. Black Beauty, Brendon Chase, The

Little Grey Men. The Brothers Lionheart,

Finn Family Moomintroll, Martin Pippin in the Daisyfield. The Enchanted Castle,

Mary Poppins, The Bogwoppit. The Land

of Green Ginger, The

Little House on the Prairie, A Christmas Carol.

The King of the Golden

River, The King of the Copper Mountains,

the Chronicles of Narnia. Anne of Green Gables, Tuck Everlasting, The Search for

Delicious. And many, many more.

Of course not every single book was a success. Neither child cared for Anne of Green Gables,

to my surprise; and they never thought much of Jo March, either. Are today's children so used to independent, strong-minded

heroines that flaming-haired Anne and hot-tempered

Jo have paled in comparison? Both daughters regarded the March sisters as a bunch of wimpish goody-two-shoes

who gave away their Christmas breakfast.

And that was that.

One child loved The Little White Horse by Elizabeth Goudge;

the other was less keen. One went a bundle on The Treasure Seekers; her sister felt lukewarm about

it. ‘Swallows and Amazons’ was an utter

failure. I loved that book when I was a

child (I remember when I first saw it, in a row of children’s books in the

dark, glass-fronted bookcase on the landing of some farmhouse where we’d gone

on holiday), but it fell completely flat as a read-aloud. I don’t know why. Maybe Ransome’s meticulous descriptions of how to do things – whether sailing a

boat, building a campfire, or setting up a pigeon post – work better on the

page? At any rate, this was the one and

only book I ever read aloud which really did bore them to the point where I

gave up, and we found something ‘more interesting’. Even the Narnia stories, which they enjoyed

hearing, turned out not to be books they went back to re-read. But they did go

back, again and again, to read many of these books and authors by themselves.

There’s something quite emotional about reading to your

children, especially stories with which you feel a special connection. Books I read with total composure as a child can now

bring tears to my eyes, and I have developed a family reputation for doing a wobble

on the last page. Black Beauty in old age, dreaming of the past:

‘My troubles are all over and I am at home; and often,

before I am quite awake, I fancy I am still in the orchard at Birtwick,

standing with my old friends under the apple trees.’

Or: ‘They thought he

was dead. I knew he had gone to the back

of the north wind.’

Or: ‘It is autumn in Moomin valley – for how else can spring

come back again?’

I’d be struggling to keep my voice level, and tears would

come brimming up. The children pounced on this. They would sit up as I turned

the last page, watching me like hawks for any signs of sentiment. They regarded

it as funny but embarrassing. “Oh Mum… Why do you always cry?” And this made me self-conscious, till,

conditioned by their expectations, I’d be brimming up – and laughing too – on

the last page of almost any book I

read aloud, even ones which weren’t sad at all.

I reckoned it was their fault for staring at me and making me worse. But

it didn’t matter. I didn’t mind then, and I don’t mind now.

For it can't be a bad thing, can it - to let our children see how stories move us?

For it can't be a bad thing, can it - to let our children see how stories move us?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)