by Jane Rosenberg LaForge

A combination of “Beauty and the Beast” and “Cinderella’’, with an equal part of “The Cat-Skin’’ and a good dose of

Job, “The Bearskin” (Der Bärenhäuter in the original German) is a tale of one

man testing his endurance against the Devil’s. Some versions of the story, such

as the one told in the Philippines, don’t necessarily pronounce a winner in

this contest. But the original Grimm’s fable makes it abundantly clear: the

Devil triumphs again. At times the story has been known as “The Devil, a

Bearskin” (Der Teufel ein Bärenhäuter) as if to reinforce this idea. The

Bearskin, a starving young man who makes his deal with the Devil so he might

survive, undergoes a transformation, but he is no Cinderella, and no friendly

and misunderstood Beast either. But this story, I have come to understand,

still has had its own impact on the culture, or at least on mass entertainment.

In traditional tellings of “The Bearskin,”

a soldier without a war to fight has no food, money, or shelter, and no

prospects of finding any; his brothers have rejected him. He appears to be

close to suicide when a cloven-hoofed creature in a green jacket reveals

himself, and offers a way out. The green jacket will produce all the money he

needs if the soldier does not say the Lord’s Prayer; if he does not wash, cut

his hair, or clip his nails—if he becomes a monster by sleeping, eating, and

living in a bearskin the Devil has just harvested from a bear that threatened

to kill the both of them, moments earlier. If the soldier can live as the Bearskin

for seven years, he’ll be returned to his natural state again.

Without any options, the soldier says

yes. He wanders about the country, paying poor people to pray for him; and his

transformation from man to monster is gradual. Eventually, though, he is forced

to retreat to a room at an inn because his appearance is so appalling. While at

the inn, he hears a man in great distress, and discovers the man has lost his

fortune. He offers to help the man by giving him money; to thank him, the man promises

Bearskin one of his three daughters in marriage. The two older daughters refuse

Bearskin, but the youngest agrees because Bearskin has helped her father. Bearskin

breaks a ring in two, gives half to this daughter, and keeps the other half.

Then he leaves to complete his odyssey.

After serving his seven years, the

Bearskin summons the Devil and demands that he be cleaned up; in some versions,

he forces the Devil to say the Lord’s Prayer. He then returns to the inn to

retrieve his bride but is mistaken for a more desirable colonel; the two older

daughters vie for his attentions. But by presenting his half of the ring, he

reveals himself to the youngest daughter and declares: “I am your betrothed

bridegroom, whom you saw as Bearskin. Through God's grace I have regained my

human form and have become clean again." When the older sisters see

the two embracing, they are overcome with rage and anger. One sister hangs

herself; the other drowns herself in a well.

The Devil

arrives at the home of the new bride and groom that evening. "You see, I now have two souls for the one of yours,’’ he says,

referring to the two sisters’ suicides. And so the tale ends. Maybe.

I was raised in the 1960s in the United States, so what I knew from

fairy tales came in the form of Disney movies, books, and costumes. “The

Bearskin” was not suitable for such purposes. Perhaps there was no way for

Disney to tidy up its message. I did not encounter “The Bearskin” until

graduate school, when I was studying German as part of my English degree. “Der

Bärenhäuter” was one of the short selections in our textbook. This is appropriate,

since fairy tales are one way we pass language and all its shadings onto our

children, and yet at the same time, I was too old, and possibly too cynical, to

buy into its message.

Because the story appeared in a language

instruction book, it emphasized the vocabulary we were studying at that time,

so my recollection of the story is filled with the many irregular verbs that

must have described how uncomfortable the bearskin was for the soldier. I also

remember the young man who leases his soul to the Devil not as a soldier but as

a profligate who wakes up after a bender to find himself in dire straits, and

this is truly his motivating factor. I was so certain that this was the case

that I complained to the professor about the Bearskin’s supposed conversion. He

was paying people to pray for him, I argued. He didn’t make any essential

changes in his own thought or nature. The instructor laughed, as he would many

more times with me, because he served as an advisor on other translation projects

I worked on, and to which I added far more errors than I ever did with “The

Bearskin.”

German is a language I have studied for

many years, and both my memory and my initial understanding of “The Bearskin” are

tied up in that experience. My grandfather and uncle, with whom I briefly lived

while in high school, both spoke German, and the language was their go-to code

when they were deciding how to discipline me for some adolescent infraction. I

thought if I could learn it, I could figure out what they were saying. I still

have no idea what they were planning. That also seems appropriate, considering

the Job-like tests they put me through, although they were only Job-like

because of my limited perspective.

Now that I have given myself permission

to think about the story in English, I can see how ingeniously it was put

together, for the Devil and the soldier reverse roles toward the end of the

story, when Bearskin demands penance from the Devil. But crime does not pay in

fairy tales; it doesn’t pay for Rumplestiltskin, for example, and the new

family created in the process of the Bearskin’s rebirth cannot live happily ever

after without some sacrifice. This back-and-forth seems to be a reflection of

the language that bore this story, with its flexible syntax, but only to a

point: the action, or the verb, always has the same position in a sentence. And

the Devil always wins.

Bruno Bettlelheim, in his introduction to

The Uses of Enchantment, argues that

religious motifs and morals have always been a part of fairy tales; Jack Zipes,

in his introduction to Fairy Tales and

the Art of Subversion, blames conservative religious forces for sanitizing

fairy tales as early as the 17th century. Nevertheless, the warnings of “The Bearskin”

are unmistakably grounded in Christianity, given its plot, and it lends a

theological interpretation to tales such as “Cinderella.’’ In light of “The

Bearskin,’’ Cinderella’s makeover at the hands of the Fairy Godmother is as

joyous as an Easter resurrection. Together with “The Cat-Skin,’’ these fairy

tales demonstrate the gamut of the possibilities in the rebirthing process:

from poor to rich; from rich to poor; maddeningly temporary or rewardingly

permanent. (The story bears, for lack of

a better word, other striking similarities to “The Cat-Skin;’’ the retreat into

an animal identity for the protagonist, and the contrivance of jewelry, hidden

in food or drink, to reverse that identity back to a worthy human one again.)

I am particularly impressed by the

religious nature of this tale, given my early education within the wallet of

Walt Disney, who did not care to muddy his profit margin with tenants of charity

and self-sacrifice. Yet at the same time, “The Bearskin” is deterministic, or

fatalistic, in its faith that the Devil can work his way around the most

valiant of men. There is no God in this text, or at least not an explicit God

who extends a visible and helping hand to one of his flock. The only assistance

he has, he finds from other imperfect humans like himself. Man is on his own

here. The soldier saves himself, which some might argue makes “The Bearskin”

fulfill an essential function of a fairy tale: showing the powerless or

marginalized a path to power, or at least one out of the peril they thought

they could not escape.

I have my daughter, a voracious consumer

of science fiction and urban fantasy books, television, and movies, to thank

for explaining the story’s discomfiting end. When someone is rescued from Hell, she said, that

person has to be replaced by another soul, to maintain the balance between

worlds. So of course the Devil, after losing possession of the soldier’s soul,

would attempt to replace it—if not improve on his investment.

For close to two decades I have been

turning “The Bearskin” over in my mind, so much so that I have made it the

centerpiece of the next modern fairy tale I hope to write. So perhaps this tale

is not quite finished, after all.

Jane Rosenberg LaForge lives and writes in New York City. She is the author of "An Unsuitable Princess: A True Fantasy/A Fantastical Memoir'' (Jaded Ibis Press 2014); three chapbooks of poetry, and one full-length poetry collection, "With Apologies to Mick Jagger, Other Gods, and All Women" (The Aldrich Press 2012). Her poetry, fiction, and essays have appeared in numerous online and print journals, such as THRUSH, Fruita Pulp and The Linnet's Wings; and she has been twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize. More information is available at jane-rosenberg-laforge.com.

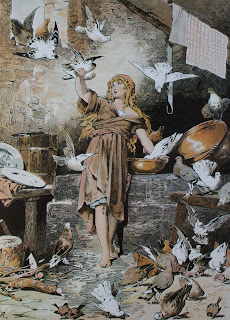

Picture credits:

Bearskin - Arthur Rackham

Bearskin - Louis Rhead

Bearskin - John Gruelle

Jane Rosenberg LaForge lives and writes in New York City. She is the author of "An Unsuitable Princess: A True Fantasy/A Fantastical Memoir'' (Jaded Ibis Press 2014); three chapbooks of poetry, and one full-length poetry collection, "With Apologies to Mick Jagger, Other Gods, and All Women" (The Aldrich Press 2012). Her poetry, fiction, and essays have appeared in numerous online and print journals, such as THRUSH, Fruita Pulp and The Linnet's Wings; and she has been twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize. More information is available at jane-rosenberg-laforge.com.

Picture credits:

Bearskin - Arthur Rackham

Bearskin - Louis Rhead

Bearskin - John Gruelle