Please don't worry though! Actually the bad news isn't so bad. I'm about to take a break from this blog, but I fully intend to be back here some time in the autumn with a new selection of wonderful guest writers, Magical Classics, Folklore Snippets, and possibly even Fairytale Reflections, as well as anything else that strikes me about the wonderful world of folklore, fairytale and fantasy.

I began 'Steel Thistles' in December of 2009, and I've been blogging pretty well steadily ever since, at least once a week and sometimes more. I've enjoyed every moment of it. But - and here is the good news! - during that time I've also been researching and writing my new book. In fact, I even mentioned the book in that very first post of more than four years ago - which is a rather scary thought! It's the longest I've ever taken over writing a book - I'm one of those 'revise as you go' writers - and I'm now finally beginning the last chapter.

I'll tell you a little tiny bit about it: it's YA (ie: for Young Adults), and it's set in the future, in the same world as the short story 'Visiting Nelson' which I wrote for the Terri Windling/Ellen Datlow anthology AFTER (whose cover you can see in the right hand column). I've been living and dreaming it for so long, I can hardly believe I'm nearly there. (Except, and this is good,the next thing I have to do is write the sequel!)

So, dear reader, I need to take time off, have a breathing space, let the well of inspiration refill - all that stuff. In the mean time, I hope you'll keep visiting, because I'm going to be reposting one of my older posts each week, things you may have not seen - or forgotten. Also, I'd like to tell you again the story of how this blog got its rather strange title - 'Seven Miles of Steel Thistles'.

It comes from a phrase in a West Irish fairytale called The King Who had Twelve Sons, in which the hero has to ride 'over seven miles of hill on fire, and seven miles of steel thistles, and seven miles of sea'.

I read that, and I thought it was a good metaphor for life in general and the craft of writing in particular. It can be a long hard journey, but you get there. In the end.

Even though I won't be writing new posts for a while, I'll be dropping in myself regularly, so I hope you'll leave comments, and we can keep talking. And here's the very first post I ever wrote for this blog, with that reference to the now-almost-completed-book.

See you in the autumn!

THE ECONOMY OF MORDOR

For nefarious reasons

connected with my next book, I’ve been investigating towers, and as one

thing leads to another and fictional towers tend to carry the mind to

Dark Towers, I found myself – and not for the first time – considering

the economy of Mordor. You could hardly complain about the amount of

creative thought and background research that JRR Tolkien put into

creating the world of Middle-Earth, but he was undeniably stronger on

history and languages than he was on geography and economics.

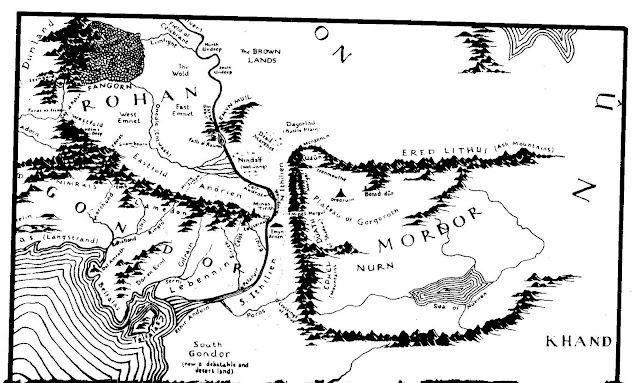

A look at the map is

instructive. Mordor is a landlocked country, surrounded on three sides

by suspiciously straight lines of mountains. In the north-west is the

Plateau of Gorgoroth, perhaps volcanic; doubtless dry and cold, for no

rivers run from it. To the south-east is the low-lying and bitter Sea of Nurnen.

No navigable rivers flow out of Mordor, though the River Harnen has its

source just beyond the southern border. The Great River Anduin curves

provocatively close to Mordor’s western frontier, but there appear to be

only two passes through the Ephel Duath: Minas Morgul represents one;

the Morannon or ‘Black Gate’ the other.

Trade-routes to the

west, therefore, are few and far between. To the east Mordor lies open,

but although we sometimes hear of ‘Easterlings’or ‘Wainriders’ –

enemies of Gondor – they are characterised as wild nomadic tribesmen,

unlikely sources of supplies. South Gondor

is marked on the map as ‘a debatable or desert land’, and Near Harad,

Haradwaith and Khand appear utterly devoid of forests, rivers, cities or

hills. It’s a complete puzzle how the ‘Southrons’ who ally themselves

with Mordor find the resources to muster their vast armies mounted on

oliphaunts.

Mordor itself is an

ecologist’s nightmare: a wasteland of slag and ash, scored with gaping

fissures and rocky ridges, governed by an evil all-seeing Eye on the top

of a vast Dark Tower

not too far from an active volcano which pours out ever more ash and

smoke. Nothing grows. There’s hardly any rain, and any trickle of

water running through the polluted land swiftly becomes poisoned.

In the course of rescuing Frodo from the Tower of Cirith Ungol,

Sam raises a question that suggests Tolkien may have experienced a

slight frisson of doubt about the non-availability of food in Mordor.

‘Don’t orcs eat, and don’t they drink? Or do they just live on foul

air and poison?’ Frodo assures Sam that on the contrary, orcs do eat:

‘Foul waters and foul meats they’ll take, if they can get no better, but

not poison.’

Armies, as we know,

march on their stomachs. I can see that an enormous fiery Eye isn’t

going to care that in all his wide lands there’s not a bite to eat; and

the Nine Ringwraiths probably don’t mind much either. But the orcs?

How do they benefit from serving Sauron? And Frodo watches whole armies

marching into Mordor via the northern Black Gate: ‘men of other race,

out of the wide Eastlands, gathering to the summons of their

Overlord.’ What on Middle-Earth are they thinking of? What can they

expect to gain from rallying to the aid of a Dark Lord who rules a

bankrupt country with no agriculture, no exports or imports and no

internal food supplies? There isn’t even the prospect of future riches

if Gondor falls to Sauron – for in that case Gondor itself will become a

similar wasteland.

In any normal world

economy, Mordor would be over its ears in debt. Refugees – orcs,

Easterlings and Southrons – would be streaming westwards in the hope of

better lives for themselves in Gondor. Rather than closing its gates

against an invading army, Minas Tirith would be coping with an influx of

immigrants. The tough and hardy orcs would hire themselves out as

cheap labour in exchange for a few coppers and a square meal. Mounted

bands of Rohirrim would patrol the borders of Rohan to turn away

fugitives. Dark Lord or no Dark Lord, Sauron would have no choice but

to borrow money from the coffers of Minas Tirith – or from the

metal-rich dwarfs – in order to keep Mordor from emptying itself. The

power is with the purse strings.

Still, The Lord of the

Rings is not a political satire. Perhaps we can be grateful that

Tolkien didn’t look too closely at the economy of Mordor. Middle-Earth

is a polarised world. The brave, the beautiful and the good are all

grouped together on one side, while the wicked, the ugly and the cruel

gravitate together on the other. So let’s hear it for the all-powerful

Dark Lord, Ruler of the Wastelands, Commander of Ringwraiths, Leader of

the Axis of Evil.

So long as we remember he doesn’t exist.

(21 December 2009)

Picture credits: John Bauer: illustration from The Ring - the link is here, with a fascinating essay about visual influences on Tolkien's world: http://www.touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=15-01-041-f

Map of Mordor, from The Return of the King.

Have a lovely breathing space. Breathe long, deep and well and come back invigorated. xx

ReplyDeleteHope you have a good rest from the blog.

ReplyDeleteI look forward to revisiting older posts, and to the Autumn offerings.

That's exciting news about being in the home stretch with your book! All the best with it and the sequel.

I will miaou-iss you but hsve a purr-fect break!

ReplyDeleteThank you my dears!

ReplyDeletePS: You will also find me on the 4th of every month blogging at The History Girls - http://the-history-girls.blogspot.co.uk/

ReplyDeleteLooking forward to seeing your new book when it's out. And thanks for the repeat post, which I have not read before. Actually, somewhere in LOTR Tolkien does mention vast plantations with slave labour somewhere in Mordor, but it's hard to imagine how you could grow anything there, let alone feed the workers. I have never understood what would be the fun of being a Dark Lord if you had to live somewhere horrible. And you're right about the geography. Mapmaker and fantasy writer Russell Kirkpatrick gave a talk about why the Mines of Moria wouldn't work geographically. He did it with much affection, though.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Sue! I don't remember the plantations - but I suspect it of being a sop to credibility! I do love LOTR, though, I hasten to add. And the bit in the Mines of Moria is my favourite part - so I'm sorry to hear the Mines are geologically impossible! - not as impossible as the gigantic hollow caverns in the films, though.

ReplyDeleteI too hope you have a lovely break, and that your book cooperates!

ReplyDeleteThankyou!

ReplyDelete