|

| Persephone as throned goddess of the underworld |

The Greek myth of Persephone has often been retold as a sweet

and charming little story, a just-so fable about the cycle of winter and

spring. Here’s an extract from a 19th century version for children,

‘The Pomegranate Seeds’ by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Persephone (under her Roman

name, Proserpina) has begged Mother Ceres for permission to pick flowers, when,

attracted by an unusually beautiful blossoming bush, she pulls it up by the

roots. The hole she has created immediately spreads, growing deeper and wider,

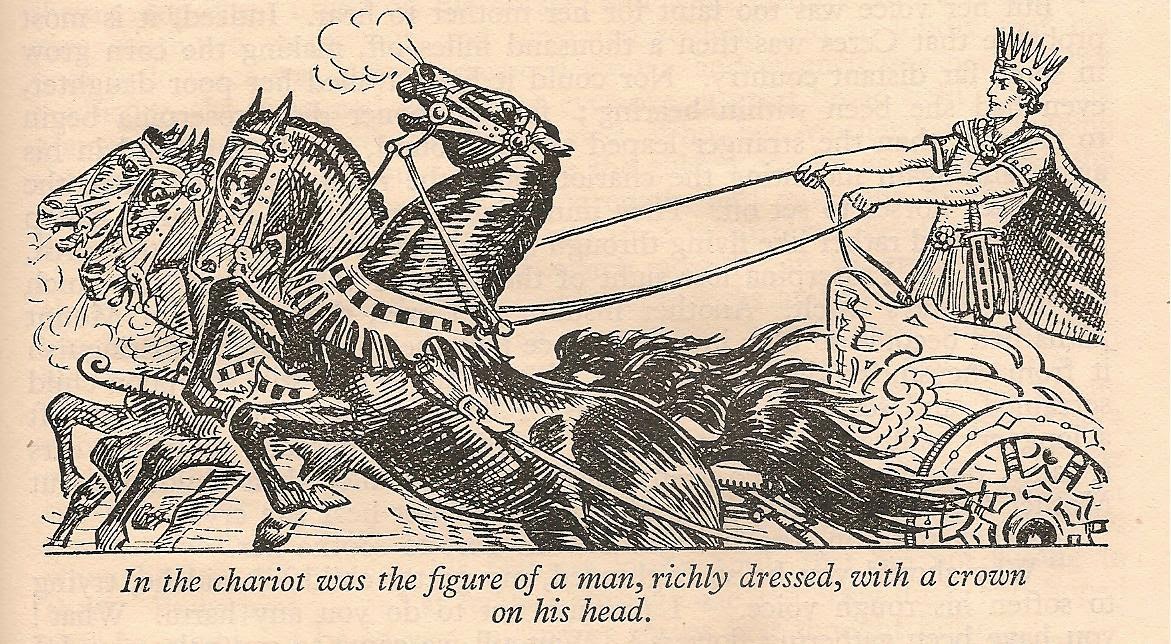

till out comes a golden chariot drawn by splendid horses.

In the chariot sat the figure of

a man, richly dressed, with a crown on his head, all flaming with

diamonds. He was of a noble aspect, but

looked sullen and discontented; and he kept rubbing his eyes and shading them

with his hand, as if he did not live enough in the sunshine to be very fond of

its light.

“Do not be afraid,” said he, with

as cheerful a smile as he knew how to put on. “Come! Will you not like to ride a little way with

me in my beautiful chariot?”

Reducing the myth to a 19th century

version of ‘don’t get into cars with strange men’, Hawthorne tells how King

Pluto (something of a spoiled Byronic rich boy) makes off with the ‘child’

Proserpina and takes her into his underground kingdom, where she refuses to

eat. Archly, Hawthorne explains that if only King Pluto’s cook had provided her

with ‘the simple fare to which the child had been accustomed’, she would

probably have eaten it, but because ‘like all other cooks, he considered

nothing fit to eat unless it were rich pastry, or highly-seasoned meat’ – she

is not tempted. In the end, of course, Mother Ceres finds her daughter, and

Jove sends ‘Quicksilver’ to rescue her but not before (‘Dear me! What an everlasting pity!’) Proserpina has

bitten into the fateful pomegranate – and her natural sympathy for the gloomy

King Pluto leads her to declare to her mother, ‘He has some very good

qualities, and I really think I can bear to spend six months in his palace, if

he will only let me spend the other six with you.’

And lo, the happy ending. Prettified as this is, no one

would guess that Persephone – whose name means 'she who brings doom’ – was

one of the most significant of Greek goddesses. In Homer, it is to her kingdom

which Odysseus sails:

Sit still and let the blast of

the North Wind carry you.

But when you have crossed with

your ship the stream of the Ocean

you will find there a thickly

wooded shore, and the groves of Persephone,

and tall black poplars growing,

and fruit-perishing willows;

then beach your ship on the shore

of the deep-eddying Ocean

and yourself go forward into the

mouldering home of Hades.

The Odyssey of Homer, Book X, tr. Richmond

Lattimore, Harper & Row, 1965

As Demeter’s daughter, she is originally named simply ‘Kore’

or ‘maiden’. When Kore is stolen away, Demeter searches for her throughout the earth, finally stopping to rest at Eleusis, outside Athens. There, disguised as an old woman, she cares for the queen's son,

bathing him each night in fire so that he will become immortal. When the

queen finds out, she interrupts the procedure and the child dies. The angered goddess throws off her disguise, but in recompense teaches the queen's other son, Triptolemos, the art of agriculture. Meanwhile, since the crops are dying and the earth will

remain barren until Demeter's daughter is restored, Zeus persuades Hades to return Kore to her mother - so long as no food has passed her lips. But Hades has tricked Kore

into eating some pomegranate seeds, and she must therefore spend part of every year in Hades. Kore emerges from the underworld as

Persephone, Queen of the dead. And a temple is built to Demeter and Persephone at Eleusis, which every year will host the Great and the Lesser Mysteries. The participants would:

[walk] the Sacred Way from Athens to Eleusis calling for the Kore and re-enacting Demeter's search for her lost daughter. At Eleusis they would rest by the well Demeter had rested by, would fast, and would then drink a barley and mint beverage called Kykeon. It has been suggested that this drink was infused by the psychotropic fungus ergot and this, then, heightened the experience and helped transform the initiate. After drinking the Kykeon the participants entered the Telesterion, an underground `theatre', where the secret ritual took place. Most likely it was a symbolic re-enactment of the `death' and rebirth of Persephone which the initates watched and, perhaps, took some part in. Whatever happened in the Telesterion, those who entered in would come out the next morning radically changed. Virtually every important writer in antiquity, anyone who was `anyone', was an initiate of the Mysteries.

(Professor Joshua J. Mark on the Eleusinian Mysteries, at this link: http://www.ancient.eu.com/article/32/)

[walk] the Sacred Way from Athens to Eleusis calling for the Kore and re-enacting Demeter's search for her lost daughter. At Eleusis they would rest by the well Demeter had rested by, would fast, and would then drink a barley and mint beverage called Kykeon. It has been suggested that this drink was infused by the psychotropic fungus ergot and this, then, heightened the experience and helped transform the initiate. After drinking the Kykeon the participants entered the Telesterion, an underground `theatre', where the secret ritual took place. Most likely it was a symbolic re-enactment of the `death' and rebirth of Persephone which the initates watched and, perhaps, took some part in. Whatever happened in the Telesterion, those who entered in would come out the next morning radically changed. Virtually every important writer in antiquity, anyone who was `anyone', was an initiate of the Mysteries.

(Professor Joshua J. Mark on the Eleusinian Mysteries, at this link: http://www.ancient.eu.com/article/32/)

The story really does contain all those mythic,

seasonal references. While Persephone is in the underworld, the plants wither and die; there are the scattered flowers

dropped by the stolen girl, there are the significant pomegranate seeds: but this is much more than

a pretty fable. It’s a sacred story which conveyed to the initiate the promise and comfort of life after death.

A couple of years ago, I went to see an exhibition of

treasures from the royal capital of Macedon, Pella, at the Ashmolean Museum

in Oxford. The

treasures were dazzling, and the exhibition also included photographs of the

lavish interiors and furnishings of the royal tombs of Philip II (father of

Alexander the Great) and his family, at Aegae. In the tomb of Philip’s mother, Euridike,

was a fabulous chair or throne. On its

seat had rested the chest containing the Queen’s burned bones, wrapped in purple...

...while on the back of the throne is a

painting depicting Hades and Persephone riding together in triumph on their

four-horse chariot. In another tomb at Aegae, Demeter is shown lamenting the

loss of Persephone, while on another wall, Hades carries her off. For me, it seems these images are being used

in much the same way that we would place a cross on a Christian tomb. They are

not merely referencing, but calling upon a significant myth, a myth with

immediate, emotional potential, a myth that speaks of life beyond the doorway

of death.

Although these tombs belong to the Classical era, in many

ways the Macedonian royals had more in common with the heroic Mycenean age of a

thousand years earlier. Many Macedonian consorts acted as priestesses as well as

queens. At the funeral pyre of Philip II, in 336 BC, it’s

startling to learn that his youngest wife, Queen Meda, went to the flames with

him, along with the dogs and horses which were also sacrificed. But she was quite likely a willing

victim. Dr Angeliki Kottaridi explains;

‘According to tradition in her country, [this] Thracian princess followed her

master, bed-fellow and companion forever to Hades. To the eyes of the Greeks,

her act made her the new Alcestes [in Greek mythology, a wife who died in her

husband’s place] and this is why Alexander honoured her so much, by giving her,

in this journey of no return, invaluable gifts’ – for example, a wreath of gold

myrtle leaves and flowers:

Dr Angeliki Kottaridi again:

In the Great Eleusinian

Mysteries, Demeter gave to mankind her cherished gift, the wisdom which beats

death. With the burnt offering of the breathless body, the deceased, like

sacrificial victims, is offered to the deity. Through their golden bands [pictured

below] the initiated ones greet by name the Lady of Hades, the ‘fearsome

Persephone’. …Purified by the sacred

fire, the heroes – the deceased – can now start a ‘new life’ in the land of the

Blessed; in the asphodel mead of the Elysian Fields.

Dr Angeliki Kottaridi: “Burial customs and beliefs in the royal

necropolis of Aegae”, from ‘Heracles to Alexander the Great, Treasures from the

Royal Capital of Macedon’, Ashmolean

Museum, 2011

For me, one of the most moving items in the exhibition was this

small leaf-shaped band of gold foil, 3.6 cm by 1 cm. Upon it is impressed the simple message:

ΦΙΛΙΣΤΗ ΦΕΡΣΕΦΟΝΗΙ ΧΑΙΡΕΙΝ

Philiste to Persephone, Rejoice!

And I wonder, I wonder about that leaf-shape. The goldsmiths of Macedon were unrivalled at creating wreaths – of oak

leaves and acorns, or of flowering myrtle that look as though Midas has touched

the living plant and turned it to gold. Would such artists really have used any

old ‘leaf shape’ – or is this slim slip a gold imitation of the narrow leaf of

the willow – the black, ‘fruit-perishing willows’ which Homer tells us fringe the

shores of Persephone’s kingdom?

Picture credits:

Statue of Persephone: ca 480–460, found at Tarentum, Magna Graecia (Pergamon Museum, Berlin)

Illustrations of Hawthorne's 'The Pomegranate Seeds' from 'The Mammoth Wonder Book': 1935

Photos of Macedonian tomb and goods from Heracles to Alexander the Great, Treasures from the Royal Capital of Macedon’, Ashmolean Museum, 2011

Wonderful, Kath. I was bowled over by the Greek Myths when I was about ten - and my first meeting with them was with these versions for children. As I grew older, it began to dawn on me that the myths had a far more - well, mythic, significance. And I began to make connections with other myths of death and rebirth - Astarte, Adonis, Frey and Balder. I rather enjoyed that growing, deepening understanding. And, probably, the ancients themselves made a similar journey from simple little fairy-story to myth.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting read. I love how fairytales are all bound up with old myths, and how you can trace the journey from myth to fairytale to modern story.

ReplyDeleteWonderful post! Have you encountered the Cobweb Bride trilogy by Vera Nazarian? To my mind, a really creative take on the Persephone story. Her characters are well drawn, deep ... often terrifying and one could say the same for the plot. I'll stop gushing and send a link for more: http://www.norilana.com/cobweb.htm

ReplyDeleteOoh, thankyou!

ReplyDeleteAnother wonderful read - Oh, you have found an avid blog follower in me today :)

ReplyDeleteThankyou, Morgan!

ReplyDeleteIt's interesting to me that we come at the story of Persephone (as we do all legends of origin) as something long past. When we read about the maiden, she's already well-established as "fearsome Persephone." It's like they got together and said, "It couldn't have always been this way . . . what happened?"

ReplyDelete