When you open this blog you should be greeted by a Google message which reads as follows:

This site uses cookies from Google

to deliver its services and to analyse traffic. Your IP address and user

agent are shared with Google, together with performance and security

metrics, to ensure quality of service, generate usage statistics and to

detect and address abuse.

In addition to this I should like to assure followers that this is a non-commercial blog. As owner, I make no use of any data you may have had to provide to sign up. I have not and never will contact any follower or reader, outside of the public conversation, via comment and reply, visible at the foot of each post.

Tuesday, 29 May 2018

Seven Miles of Steel Thistles and GDPR: a note

When you open this blog you should be greeted by a Google message which reads as follows:

Thursday, 30 November 2017

Seven Miles of Steel Thistles, reviewed by Jacqueline Simpson

Good reviews are always lovely to receive, but sometimes you receive one which means more than most. This, from the almost legendary Jacqueline Simpson, sometime President of the Folklore Society, Visiting Professor of Folklore at the Sussex Centre of Folklore, Fairy Tales and Fantasy at the University of Chichester, collaborator with Terry Pratchett on The Folklore of Discworld and co-author with Jennifer Westwood of The Lore of the Land: a Guide to England's Legends, from Spring-heeled Jack to the Witches of Warboys - is truly special. So here it is, from the latest issue of 'Folklore' and please forgive me for a little trumpet-blowing.

Seven Miles of Steel Thistles:

Reflections on Fairy Tales. By Katherine

Langrish. Carterton,

Oxfordshire: Greystones Press, 2016. 292 pp.

£12.99 (pbk). ISBN 978-1-91112-204-3

‘Fairy tales’, writes Katherine Langrish,

‘are emotional amplifiers . . . [They] work as music does,directly on our

feelings’ (197). This collection of her essays (plus three poems) illustrates

the psychological subtlety and poetic force of her own responses, and will

surely guide readers towards similar sensitivity. She can also, on occasion,

cast light on relationships of sources and analogues, notably in her discussion

of the ballad of ‘The Great Selkie of Sule Skerry’ (158–87), but her main

concern is usually with the deeper themes which she perceives as underlying

fairy-tale plots—such themes as time, hunger, death, and rebirth. Alongside

these, she can provide sudden sharp insights and speculations which even if

unprovable will remain memorable and interesting. For example, in an essay on

water spirits she wonders whether the fact that a stick plunged into water will

appear broken although it is in fact unharmed could have inspired the

prehistoric custom of bending or breaking weapons before throwing them into

sacred pools (262). She boldly tackles even the apparently distasteful tale of

‘The Juniper Tree’, which ‘acknowledges terrible evil but ends in hope’ and

which ‘haunts’ her (145). Of course, one’s own responses may not always match

hers; for example, she has never met anyone who likes the tale of ‘Bluebeard’

(198),whereas I enjoyed it as a child—largely, as I recall, for Sister Anne’s

recurrent rhyming reply, ‘Je voie l’herbe qui verdoit et la route qui poudroit’

(I see green grass growing, and on the road dust blowing). We are all

subjective readers, and I am grateful to Katherine Langrish for showing how fruitful

this can be.

Her writing throughout is elegant, vivid, and

frequently witty; there is much pleasure, as well

as much information, to be obtained from Seven Miles of Steel Thistles.

Jacqueline Simpson, The Folklore

Society, UK

© 2017 Jacqueline Simpson

Saturday, 25 November 2017

"It's not just an [insert genre] book..."

I went into ‘The Last Bookshop’ in Oxford the other day, which sells what I assume (?) are remaindered books, since everything in the shop, regardless of size or original price, is sold for two pounds. (If not remaindered, the deal is a disgraceful one.) I buy books regularly enough that I don’t feel guilty about getting them cheap from time to time: and the selections here are often more interesting than what is to be found in the chains. Which proved to be the case as I pounced with delight upon this:

It’s the third in a series of horse

books for children, 'The Horses of Oak Valley Ranch', by Jane Smiley, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of ‘A Thousand Acres’. I

have the first two in the US hardcover

editions: ‘A Good Horse’ and ‘The Georges and the Jewels’. I do wish same-language publishers would keep to original titles, but Faber &

Faber in

the UK has changed them to the more generic ‘Secret Horse' and ‘Nobody's Horse’, and in the process designed covers that practically guarantee no-one except pony fanatics will ever read them. The US covers are way classier. But that's publishers for you. And who knows if any of them sold well?

I mean, take a look at the UK cover of 'Mystery Horse' –‘True Blue’ in the States – the gorgeous galloping white horse against the blue sky, with its blue foil title

and little blue and pink foil flowers spangled around. Any pony-mad child

would want it. But then, well, then

they might find this is more than your average pony story.

|

| US title/cover |

|

| UK title/cover |

Set in 1960’s California,

the books follow the story of a young girl, Abby, growing up in a

fundamentalist Christian family. Her father is a horse trainer and dealer, and

Abby spends much of her free time outside school helping him work with the

horses. Her mother and father are loving parents but her father in particular

is unbending in his outlook, and her elder brother Danny has left home after a bitter row.

Smiley’s treatment of the family and its predicament is

sympathetic and nuanced. As Abby is the

narrator, we see her father through her eyes: stubborn, hardworking, fair

according to his lights, rigid in his beliefs but – over the course of the

first three volumes – able finally to compromise and come to terms with his son’s

independence. In the meantime Abby

begins to navigate her own way through life. Observing her father’s strengths

and weaknesses, she learns how to trust herself, to question her parents’ views

without loss of love or respect, and to come to her own conclusions.

|

| US title/cover |

|

| UK title/cover |

And yes, there is a lot about horses. Horses, Smiley

suggests, are pretty much like people. When her father, a church elder, wants to

discipline the disruptive young sons of a church family, Abby points out that

whipping a child can be as counterproductive as whipping a horse:

“I think they [the boys] are like

Jack, not like Jefferson. If we whipped Jack,

it wouldn’t make him stop running. It

would make him run faster. If we whipped

Jefferson, he might not run at all. He might just stop and buck.”

Mom reached over and smoothed my hair. Dad didn't say anything, and we drove the rest of the way home.

As if all this wasn’t enough, ‘Mystery Horse’/’True Blue’ is

also a remarkably good ghost story: unsettling, spooky, beautiful and

ultimately all about Abby, so that

the ghostly bits are integral to the narrative and not some tacked-on extra

thrill.

As an adult, I love these books. I love the detailed and

thoughtful accounts of grooming, training and riding these horses which –

because they are all for sale – often don’t even have individual names, in case

anyone gets too attached to them. I love the fact that there

can be whole chapters set in church – the ‘church’ which is all this small

faith group can afford, a featureless rented space in a shopping mall. I love the thoughtfulness with which Jane

Smiley navigates Abby’s world. The ways

in which school and home life clash: textbooks which mention evolution and therefore

cannot be shown to Daddy, or Mom’s horror on discovering that in a history

lesson, Abby has been constructing cardboard models of Spanish missions.

‘“You built a Catholic

mission?”

“We all did.”’

It’s done with

a light, almost comedic touch, but can become serious. ‘“So,” said Daddy' [to

Daniel, at the beginning of their quarrel]. “Some boys who taught you to take the holy name of the Lord in vain

are going to pick you up and take you to see a fantasy movie about evil and

hate. Am I right?”’ Other kids are

allowed to go to movies and listen to the Beatles. Abby doesn’t exactly miss these

activities, but she knows that not having them makes her different.

I love all of this. But would a child?

Well it depends on the child. And this is where the title for this post

comes in. Genre fiction has an

undeserved bad name. Horse and pony books. School stories. Crime. Romance. Historical novels.

Science fiction. Fantasy. Children’s books. Murder mysteries. If you can put it in a category it must

somehow be less than a ‘real’ novel.

‘It’s just a pony book.’ ‘It’s

just a school story. ‘It’s just a

romance.’

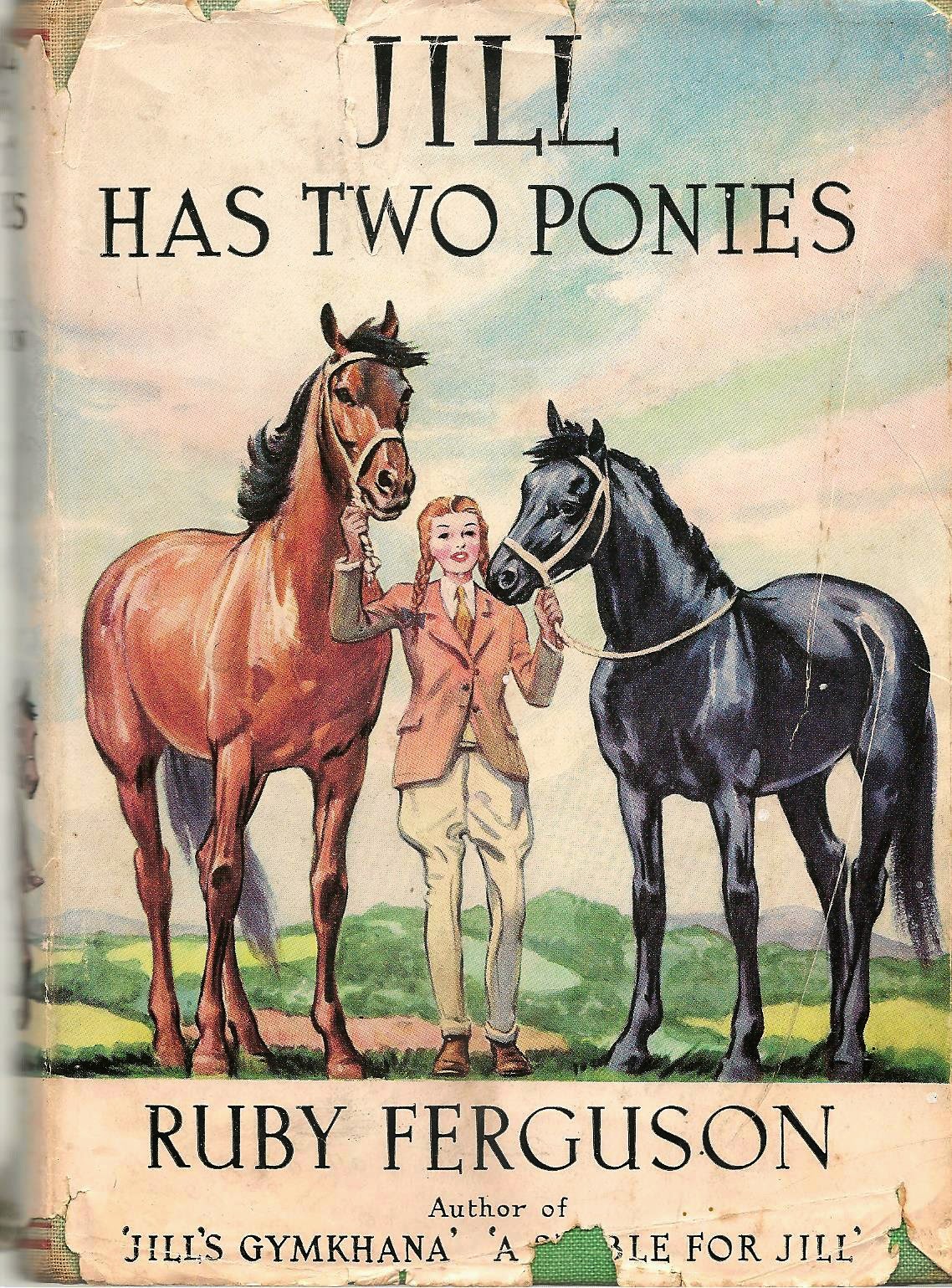

It’s true that there are many pony books, school stories and adventure stories which are hardly great literature – however that may be defined. But not every plain old novel is great literature either. I’m not denigrating the many, many pony books I read as a child just because, as an adult, I no longer find them so interesting. The ‘Jill’ books by Ruby Ferguson, for example, kept me enthralled when I was ten or eleven. They are fun, they are lively. They do one single thing: tell an entertaining story and tell it well. That is good in itself.

But there are books which do more, which are

multi-dimensional. Mary O’Hara’s ‘My Friend Flicka’ and ‘Thunderhead’ and

‘Green Grass of Wyoming’ are multi-dimensional. They offer a richness – of

characterisation, of description, of emotional intelligence – which the ‘Jill’

books don’t have and never aspired to.

KM Peyton’s ‘Flambards’ and ‘Fly

By Night’ and ‘The Team’ are multi-dimensional. In the genre of ‘school story’,

Enid Blyton’s ‘Malory Towers’ and ‘St Claire’s’ stories offer the child reader excellent ripping

yarns, unashamed fantasies of the fun and frolics of boarding-school life. But

Antonia Forest’s school stories ('Autumn Term' and its sequels) are multi-dimensional. They offer more: depth

of character, growth, change, consideration of topics such as religion,

censorship, responsibility, and the unwitting cruelty of schoolchildren to

persons they dislike.

And yes, I loved all of them indiscriminately, but the ones I read and reread

and have kept reading into adult life are the multi-dimensional books. I knew even back at the age of eleven or

twelve or thirteen that I was getting far, far more out of ‘My Friend Flicka’

than I was getting out of ‘Jill’s First Pony’.

Mary O’Hara was talking about stuff that was important to me. My father and my brothers, much as they loved

each other, used to argue. There were misunderstandings, quarrels which

sometimes burst around us like a thunderstorm. In ‘My Friend Flicka’ and its

sequels, the dreamy boy Ken and his impatient, practical father are also

negotiating a difficult relationship punctuated by storms. That story intertwines with the story of

Ken’s love for his little horse, and is just as important.

Maybe some children don’t like these multi-dimensional

books, maybe some children – perhaps even many children? – become bored,

impatient, wanting simply to get on with the story. But there will be other

children who want more, who are already thinking, already asking questions about

life, who will appreciate finding these questions taken seriously in the

middle of a book ‘about’ horses or school. A multi-dimensional book always gives the reader

more than they expected.

Am I simply saying that genre books can be good novels? Of course I am. But it’s more than that. It’s a plea.

The next time you read an excellent horse story or school story or

fantasy, try not to say in its praise, ‘It isn’t just a pony book/school story, of

course…’ as if somehow it needs to be extracted from its lowly niche before it

can be appreciated. Worse still, don’t

say, ‘It’s not really a pony book/school story/children’s book at all!’

Because if you do, if everyone who ever reads and loves a ‘genre’ book

feels they have to rescue it from its category before praising it,

then what is left? Every category

of books – novels,

children’s fiction, popular science, you name it – contains a

multiplicity of less or more able writers, and we should remember it's

better to do something simple and do it well, than to aim high and fail. If

somebody says, as someone recently said to me, ‘But Ursula Le Guin’s

books

aren’t really fantasies’, how is that a compliment to Le Guin? She chose to

employ her wonderful talent in the field of sci-fi and fantasy. That is where she belongs. All it

really proclaims is the reader’s embarrassment at having enjoyed a

book belonging to a genre which they believe – in spite of the evidence before their eyes – to be second-rate.

Either we need to do away with categories and genres

altogether – which isn’t going to happen – or we need to stop being

embarrassed and apologetic, and be ready to recognise and celebrate good work in whatever field it happens to grow. Loud and clear: there are excellent pony

books, there are excellent school stories, there are excellent fantasies and there are excellent children’s

books. Their excellence is no different

in kind from that of any other writing. So, yes! Unsurprisingly, Jane Smiley's series of horse

stories is truly excellent. Any child or adult who picks them up will learn much – about horses,

and about life.

Friday, 17 November 2017

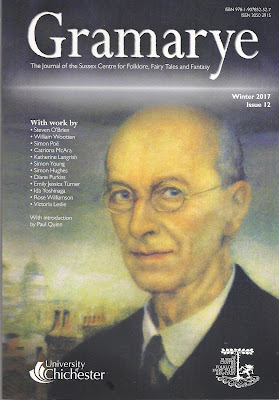

Gramarye

I am delighted to be in the new issue of GRAMARYE, the journal of the Sussex Folklore Centre and as usual an unmissable read for folk lore and fairy tale enthusiasts.This issue contains three marvellous articles on Arthur Rackham - whose self portrait adorns the cover. In 'A Walk Through Rackham Land,' Steven O'Brien takes us on a ramble through the deep history of the artist's beloved Sussex countryside. William Wootten tells how Rackham's silhouettes inspired his own verse narrative of The Sleeping Beauty, and Simon Poë interestingly compares Rackham's illustrations to 'Puck of Pook's Hill' with those of H.R. Millar. Catriona McAra contributes an article on fairy references in the work of the surrealist Leonora Carrington, while in 'Herne, the Windsor Bogey', Simon Young takes us into Windsor Great Park on a search for the controversial history of the great oak-tree of Herne the Hunter. 'The Signing Wife' is an original translation by Simon Hughes of a thought-provoking Norwegian folktale collected by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen. Finally, Diane Purkiss adds a touching and lyrical account of her childhood love for Andersen's story 'The Snow Queen'.

My own contribution is an analysis of the Grimms' fairytale 'MAID MALEEN':

Here's a little taster:

Maid Maleen (Kinder- und Hausmärchen,

tale 198) isn’t particularly popular as fairy tales go. It was first published

as Jungfer Maleen by Karl Müllenhoff

in a collection called Sagen, Märchen und

Lieder der Herzoghümer Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg (1845), from

whence the Grimms borrowed it for the 1850 edition of their Kinder- und Hausmarchen. I don’t know

whether Müllenhoff wrote it down verbatim from some oral source: he may have

touched it up, but the Grimms made several slight but significant changes to

his version, transforming it into a fairy story that delves unusually deeply

into the trauma caused by abandonment and suffering. ...

Why do I

love this story so much? Isn’t it just

another tale of a passive princess sitting in a tower? In fact there aren’t so

very many stories of princesses shut up in towers, and those that do exist are

less like the stereotype than you might suppose. As Maid Maleen does, heroines

quite often rescue themselves. Even in the case of Rapunzel (KHM 12) the

prince not only fails to rescue Rapunzel, but wanders blind in the desert until

he is saved by her. In Old Rinkrank (KHM 196), a princess trapped in a glass

mountain ultimately tricks her captor, and engineers her own escape. [...] These

tales are listed in the Aarne-Thompson folk-tale index as tale type 870: The

Entombed Princess or The Princess Confined in the Mound – though this

description, as Torborg Lundell has pointed out, is hardly adequate. Instancing

The Finn King’s Daughter, another

tale in which an imprisoned heroine digs herself out from underground and

rescues her lover from the false bride, Lundell writes:

Consistent with the Aarne and

Thompson downplay of female activity, this folktale type, with its aggressive

and capable female protagonist, has been labelled ‘The princess confined in the

mound’ (type 870), which implies a passivity hardly representative of the

thrust of the tale. ‘The princess escaping from the mound’ would fit better...

GRAMARYE issue 12 can be ordered for £5.00 from the Sussex Centre for Folklore, Fairy Tales and Fantasy by following this link: http://www.sussexfolktalecentre.org/journal/

Thursday, 26 October 2017

Folklore Snippets: The Tailor and the Corpse

From: Highland Fairy Legends, collected from oral tradition by the Rev James MacDougall (1910)

A tailor once, living on the farm of Fincharn, near the south end of Loch Awe, having denied the existence of ghosts, was challenged by his neighbours to prove his sincerity by going at the dead hour of midnight to the burying place at Kilnure and bringing back with him the skull lying in the window of the old church that gives its name to the place. The tailor replied that he would give them a stronger proof even than that, by sewing a pair of trousers in the church between bed-time and cock-crow that very night.

They took him at his word and, as soon as ten o’clock came,

the tailor entered the old church, seated himself on a flat grave-stone resting

on four pillars, and, after placing a lighted candle beside him, he began his

tedious task. The first hour passed quietly enough while he was sewing away and

keeping up his heart singing and whistling the cheeriest airs he could think

of. Twelve o’clock also passed, and yet he neither saw nor heard anything to alarm

him in the least.

But sometime after twelve he heard a noise coming from a

gravestone which was between him and the door, and on casting a side-look in

that direction he thought he saw the earth heave under it. The sight at first

made him wonder, but he soon came to the conclusion that it was caused by the

unsteady light of the candle in the dark. So, with a hitch and a shrug, he

returned to his work and sewed and sang as cheerily as ever.

Soon after this a hollow voice, coming from under the same

stone, said: “See the great, mouldy hand, and it so hungry looking, tailor.”

But the tailor replied: “I see that, and I will sew this,” and he sang and sewed

away as before.

After another while the same great hollow voice said, in a

louder tone: “See the great, mouldy skull, and it so hungry looking, tailor.”

But the tailor again answered, “I see that, and I will sew this,” and he sewed

faster and sang louder than ever.

A third time the voice spoke, and said in a louder and more

unearthly tone: “See the great, mouldy shoulder, and it so hungry looking,

tailor.” But the tailor replied as

usual, “I see that, and I will sew this,” and he plied the needle quicker and

lengthened his stitches.

This went on for some time, the dead man showing next his

haunch and finally his foot. Then he

said in a fearful voice: “See the great, mouldy foot, and it so hungry looking,

tailor.” Once more the tailor bravely answered: “I see that, and I will sew

this.” But he knew that the time for him to fly had come. So, with two or three

long stitches and a hard knot at the end, he finished his task, blew out the

candle, and ran out at the door, the dead man following him and striking a blow

aimed at him against one of the jambs, which long bore the impression of a hand

and fingers.

Fortunately the cocks of Fincharn now began to crow, the

dead man returned to his grave, and the tailor went home triumphant.

Art: Ruins of a Gothic Chapel by Moonlight, by Felix Kreutzer, 1835 - 1876

Thursday, 5 October 2017

The Terror of Trees

Ellum he do grieve,

Oak he do hate,

Willow do walk

If you travels late.

This old Somerset rhyme is quoted by KM Briggs in ‘The

Fairies in Tradition and Literature’: she explains it thus: ‘The belief behind

this is that if one elm tree is cut down the one next to it will die of grief:

but if oaks were cut they will revenge themselves if they can. Willow is the

worst of all, for he walks behind benighted travellers, muttering.’ I somehow

imagine Tolkien knew a lot of tree-lore...

Elm used to be the wood coffins were made from, and elm

trees had – before Dutch elm disease cleared them from England – a nasty

reputation for dropping branches without warning. When I was a child two

enormous elms grew on either side of the gate at the bottom of our field and for reasons I’ll explain later I was afraid of approaching them after dark.

Trees are beautiful, but can also be frightening and even

dangerous. Trees, we know, are alive. When you cut them, they bleed. Maybe it

hurts them? Then they may resent it. They have voices too, whispering secrets

or roaring in anger. In ‘The Lore of the

Forest’ Alexander Porteous writes, ‘In some districts of Austria forest trees

are said to have souls, and to feel injuries done to them.’ In gales, trees

become truly dangerous and frightening. Algernon Blackwood expresses this

terror well near the end of a story, ‘The Man Whom The Trees Loved’:

The trees were shouting in the

dark. There were sounds, too, like the flapping of great sails, a thousand at a

time, and sometimes reports that resembled more than anything the distant

booming of enormous drums. The trees stood up – the whole beleaguering host of

them stood up – and with the uproar of their million branches drummed the

thundering message out into the night. It seemed as if they had all broken

loose. Their roots swept trembling over field and hedge and roof. They tossed

their bushy heads beneath the clouds with a wild, delighted shuffling of great

boughs. With trunks upright they raced leaping through the sky.

It behoves feeble humans to treat such creatures with care.

Elders are not tall or imposing trees – they are more like

tall bushes – but they bleed so freely when cut, they are considered magical.

Sometimes they themselves are witches. Christina Hole in ‘Haunted England’

gives a polite formula with which to address an elder before you attempt to cut

it: “Old Gal, give me of thy wood, and I will give thee some of mine, when I

grow into a tree.” In other tales, elders protect against witchcraft. (Perhaps

on the principle, set a thief to catch a

thief?)

Ash trees too could have a bad reputation. This may possibly

be something to do with medieval demonising of the old Nordic mythology in

which the Ash is Yggdrasil, the World Tree. In George Macdonald’s adult fairy

novel ‘Phantastes’, the hero Anodos is warned by his hostess and her daughter

to avoid the evil Ash, whose shadow threatens the fairy cottage in which he is sheltering.

‘Look there!’ she cried,‘look at his fingers!’ The setting sun was shining

through a cleft in the clouds piled up in the west; and a shadow, as of a large

distorted hand, with thick knobs and humps on the fingers … passed slowly over

the little blind.

‘He is almost awake, mother; and

greedier than usual tonight.’

‘Hush, child! You need not make

him more angry with us than he is; for you do not know how soon something may

happen to oblige us to be in the forest after nightfall.’

In Alison Uttley’s fictionalised autobiography, ‘A Country

Child’ she describes how an ash tree tried to kill her. There was a swing

fixed in it, where the child ‘Susan’ sat, swaying to and fro and looking out at

the countryside.

Then Susan heard a tiny sound, so

small that only ears tuned to the minute ripple of grass and leaf could hear

it. It was like the tearing of a piece of the most delicate fairy calico, far

away… An absurd, unreasoning terror seized her. The Things from the wood were

free. She sat swinging, softly swinging, but listening, holding her breath,

always pretending she did not care. Her heart’s beating was much louder than

the midget rip,rip, rip, which wickedly came from nowhere... A voice throbbed in

her head, ‘Go away, go away, go away,’ but still she sat on the seat, afraid of

being afraid.

Then aloud, to show Them she was

not frightened, she sighed and said, ‘I am so tired of swinging, I think I will

go,’ and she slid trembling off the seat and walked swiftly away…

Immediately the rip grew to a

thunder like a giant hand tearing a sheet in the sky, and the whole enormous

bough fell with a crash which sent echoes round the hills. The oaken seat of

the swing was broken to fragments, and

the great chains bent and crushed.

Even on a still, hot day a forest can be an awe-inspiring

place, and those who walk or work within it may not be entirely comfortable. In

the deep north-east woods of Canada, sometimes you may hear the sound of an axe

chopping, in a distant glade where no one should be, and wonder… This may be Al-wus-ki-ni-kess, the unseen

woodcutter of the Passamaquoddies. Or in winter, the terrible jenu of the Mi’kmaq may come running

through the frozen forest: a human driven mad by famine who has turned into a cannibal monster

with a heart of ice.

What about those elm trees in my childhood home? Why did

they scare me? Well, I was thirteen and I’d been reading Robert Louis

Stevenson’s book of his travels in Polynesia, ‘In the South Seas’. Here I found

a passage which raised the hairs on my head. It’s the experience of a young man

called Rua-a-mariterangi, on the island of Katui, who was on the forest margin of the beach looking for pandanus (a fruit which looks a bit like a pineapple).

The day was still, and Rua was

surprised to hear a crashing sound among the thickets, and then the fall of a considerable

tree.

Thinking it must be someone felling a tree to build a canoe,

Rua went deeper into the wood to have a chat with this presumed neighbour, when:

The crashing sounded more at

hand, and then he was aware of something drawing swiftly near among the tree-tops.

It swung by its heels downward, like an ape, so that its hands were free for

murder; it depended safely by the slightest twigs; the speed of its coming was

incredible, and soon Rua recognised it for a corpse, horrible with age, its

bowels hanging as it came. Prayer was the weapon of Christian in the Valley of

the Shadow, and it is to prayer that Rua-a-mariterangi attributes his escape.

This demon was plainly from the grave; yet you will observe he was abroad by

day. … I could never find another who had seen this ghost, diurnal and arboreal

in its habits; but others have heard the fall of the tree, which seems the

signal of its coming. Mr Donat was once pearling on the uninhabited island of

Haraiki. It was a day without a breath of wind… when, in a moment, out of the

stillness, came the sound of the fall of a great tree. Donat would have passed

on to find the cause. ‘No,’ cried his companion, ‘that was no tree. It was

something NOT RIGHT. Let us go back to camp.’ Next Sunday … all that part of

the isle was thoroughly examined, and sure enough no tree had fallen.

This was quite enough for me. Every time I had any reason to

walk down after dusk, or at night, towards those two towering elm trees, and pass under the sighing, billowing darkness of their foliage, a

creepiness stole down my spine and I could imagine all too clearly a

decomposing corpse, swinging down out of the leaves to shove its upside-down

face into mine.

Oh yes. Trees can be terrifying. Have you any stories to tell?

Picture credits:

Theodore Kittelsen: 'Into the Woods'

Arthur Rackham: Trees: from 'A Dish of Apples' by Eden Philpotts

Theodore Kittelsen: 'The Forest Troll'

Theodore Kittelsen: 'Creepy, Crawly, Bustling, Rustling'

Arthur Rackham: Black Cat: from 'Grimms Fairytales'

Arthur Rackham: Black Cat: from 'Grimms Fairytales'

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)