|

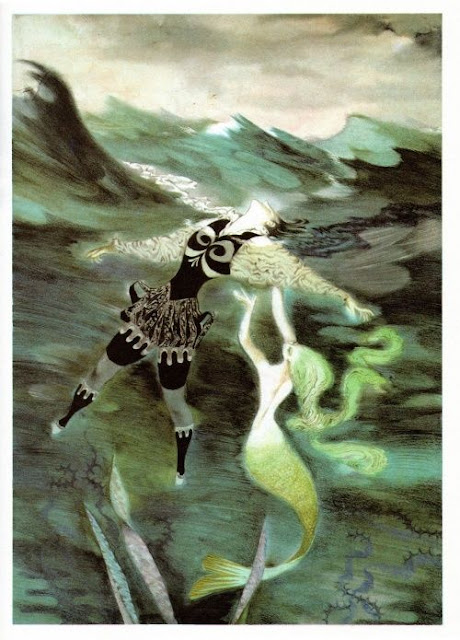

| The Little Mermaid - Edmund Dulac |

A guest post by Cassandra Golds

Once upon a time, when I was a very little girl, my father bought me and my younger sister a record.

It

was one of the Tale Spinners for Children series — a collection of

records so fondly remembered by some adults that there is a (very handy)

website devoted to them. Tale Spinners for Children was a series of

fully dramatised British adaptations of classic fairytales and stories —

everything from “The Sleeping Beauty” to The Count of Monte Christo.

They were lavishly produced in the manner of BBC

radio drama, with appropriate classical music and British actors who

were rarely credited on the sleeves, although they included such

luminaries as Maggie Smith and Donald Pleasance — and who had voices to

die for. They made some fifty of them altogether, throughout the

sixties, and incidentally the brilliant producers and adaptors were not

credited either. We as a family had several of them, but one of these

had the dread hand of fate on it. It was the Tale Spinners adaptation of

“The Little Mermaid” by Hans Christian Andersen. They used Grieg’s

Piano Concerto in A minor as incidental music, and used it so

masterfully, you would swear the work was written for the story. From

the moment I first heard it — a moment some time before I could read — I

was in love, with both the story and the concerto.

The

first time I listened to it I remember sitting on the lounge in front

of the big record player in my childhood home with an aching throat and

tears streaming down my face. The Tale Spinners version — which,

although dramatised, stuck closely to the Andersen original — was about

unrequited love, self-sacrifice and the hope of ultimate transcendence.

In other words, it was not the Disney version. And yet, at the age of

five or so, none of it seemed foreign to me. Not only did I think this

was the most beautiful story I had ever heard — immediately I conceived a

passionate allegiance to it. From this point on, for me, “The Little

Mermaid” was what a good story should be — sad, noble, uplifting,

passionate, desperate, extreme and big, opera-big. And it had to make

you cry. It was the first time I was ever moved to tears by a work of

art, and I have never fully lost the conviction that that is art’s first

duty: the gift of tears.

And

the dread hand of fate? Well, from the moment I first heard that

record, I was destined to be a children’s author. It changed the course

of my life. Or set me on it.

“The

Little Mermaid” is not a

traditional fairy tale or folk tale, but an original story by an author who is a

legend in himself. What’s more, we know a good deal about the biography

of the author, and like many of his stories, this one has strong

autobiographical overtones. We are often told that folktales were not

originally told specifically to children — that they were meant for an

audience of all ages. Original fairytales, on the other hand, such as

Andersen’s and Oscar Wilde’s, are probably more truly children’s

literature in the modern sense. And yet ever since I was an adult myself

it has struck me that “The Little Mermaid” is a very adult story. Or at

least, that it is an adult story told in the form of a children’s

fairytale. Because it takes as its subject, not (for example) every

child’s two greatest fears, as Adele Geras says so perceptively of

“Hansel and Gretel”, but unrequited love, terrible self-sacrifice, and

eventual transcendence, I have spent a good deal of time wondering what

it was that I saw in it at that age. Why did I identify with it so

strongly?

There

are a number of possible answers to that question. One thing I believe

with all my heart is that there is nothing trivial about childhood

emotion. Children may be small, but their emotions are big, as big if

not bigger than the emotions of adults. You will never be more

passionate than you are at five. Things will never matter to you more,

and you will never be capable of more suffering. It is also perfectly

possible that you have already had your heart broken. I am the eldest of

two sisters; my younger sister was born when I was eighteen months old.

It is a family anecdote that, when my beloved grandfather came to see

my baby sister for the first time, he walked past me and went first to

her in her bassinet, the new baby. I’ve been told that I ignored him

completely for the duration of the visit which followed that betrayal

and indeed that our relationship never recovered. I hope you are not

shocked — in fact I think this is a fairly ordinary family story; one

adult or another must have made that kind of crucial false step every

time a new baby has been born into this world. But I think, in common

with many children, that must have been my first experience of losing a

beloved to another, and that that was one of the things I was

recognising in “The Little Mermaid”. You learn all the basics of

romantic love before you hit kindergarten; I’m quite certain of that.

But

romantic love is not the only subject of “The Little Mermaid”. It is

also, crucially, about the longing for another state of existence; and

about dignity and even triumph in humiliation in suffering. In a way,

the Little Mermaid’s falling in love is just the trigger for a drama

about personal identity; she doesn’t just love the prince, she wants to

be him, that is, human, with an immortal soul, which in Andersen’s tale

is the exclusive preserve of human beings. And — according to the Sea

Witch — she can only truly become a human being, with a human being’s

immortal privileges, if she wins the love of the prince. The Sea Witch

can give her legs — at a dreadful price. Only the prince can give her a

soul.

|

| The Little Mermaid, Jiru Trnka |

Many

people seem to think that this story of Andersen’s is deeply

anti-feminist. I think that is a profound misreading. I’m not arguing

that he was a feminist in our terms or that he was anything other than a

man of his time. But it astonishes me that such people haven’t noticed

that he has identified himself completely with his female hero — she’s

not the Other (as women continue to be for so many male authors), she is

himself. Furthermore, she is doing something completely atypical of

traditional fairy tale heroines (or at least those belonging to the

canon of the best known) — she is the lover, not the beloved, the

active, not the passive one. Indeed, it is she who saves the prince from

drowning in a feat that would take almost impossible strength and

stamina, even for a mermaid. She’s only a fifteen-year-old girl with a

fishtail, after all, and yet she holds the insensible prince above the

waves during the entirety of a terrible storm at sea, which has wrecked

his ship, and which rages all night. Then, as the story develops, she pursues him

— but, lacking the voice she has given in payment to the Sea Witch for

the magic that will split her fishtail into legs (and less obviously but

just as importantly, being a foundling with no family or earthly

breeding) — she is unable to win his love. (And incidentally, what an

unforgettable character the Sea Witch is — laughing in scorn at romantic

love, and cutting, with the Little Mermaid, one of the most chilling

devil’s bargains in literature. And the Little Mermaid’s grandmother —

what a marvelous creation! — with all her wise counsel against reaching

too high, and being discontent with what she believes to be the pretty

good wicket of mermaid-hood.) It is also crucial to note, not only that

the Little Mermaid makes her own independent choices, creates her own

destiny, throughout the story, but also that in the overwhelmingly

powerful denouement, which is to some extent a twist, the Little Mermaid

beats the Sea Witch and even the strictures of the story itself, at

their own game. Two possible endings have been laid out for her by

others; instead — by staying utterly true to her self, her principles

and her conception of genuine love — she invents her own.

|

| The Little Mermaid - Edmund Dulac |

When I was twelve, because of the Robert Redford film, which I adored, I read "The Great Gatsby"

for the first time. It had the same effect on me as “The Little

Mermaid”, and when I was in my twenties and more capable of analysis it

dawned on me that it is exactly the same story. Gatsby is the Little

Mermaid. He, a poor boy, falls in love with a rich girl, Daisy. He

cannot win her in the state of existence into which he was born — that

is, poverty — and so he devotes his life, spectacularly, to transforming

himself into a rich boy. He gets the mansion and the money, just like

the Little Mermaid gets the legs. But he cannot win Daisy from the

husband she has chosen from her own kind, just as the Little Mermaid

cannot win the prince from his intended. For both of them, tragedy, and a

strange kind of transcendence, results.

Unrequited

love makes you question your entire existence. It is as if your whole

self is worthless, because that self is worthless, or not worth enough,

to the beloved. If you experience unrequited love profoundly, it will

have a profound effect on your personality. You will be inclined to

define yourself by it, as if it is the single most important aspect of

your personality. And it will force you to find a means of transcendence

— a sense of worth, even of personal destiny, that makes the

indifference of the beloved bearable and even creatively and spiritually

lucrative.

Here

is something I will never know, but will wonder about all my life. When

I first heard “The Little Mermaid”, was I already, at five or six, that

kind of personality who would spend much of her life loving

unrequitedly? Or could it be true — though, as a children’s author, I

hope with all my heart that it is not — that the story affected me so

deeply that it turned me into such a person?

I’m

sure you already know why I hope that’s not true. It’s because I don’t

want to have that much power. I don’t want any story to have that much

power.

Cassandra Golds, Friday 19th November, 2010

Update Friday 22 June 2012: Cassandra writes:

P.P.S. Now here, gentle reader, is a post script which I feel bound in

honour to add, for life is nothing if not surprising, and we would all

do well to remember this -- especially those of us who are authors! The

very week that I wrote this piece in late 2010 -- the very week -- I met

the man who has become the love of my life. It took until well into my

forties, but I have finally experienced a love that is not unrequited.

And so you see, “The Little Mermaid” notwithstanding, my life has turned

out quite unexpectedly. I seem almost to have gone from being a Hans

Andersen heroine to a Jane Austen one. And as Emma discovered, we are

not entirely the authors of our own biographies. For that matter, as

Catherine Morland discovered, we are not characters in our favourite

books, either! In the infinitely complex, utterly unpredictable stories

that are our lives, we never know what plot twists we will encounter --

perhaps on the very next page.

Cassandra Golds is an Australian writer of children's and YA fantasy: she and I seem to have much in common, not least that we are both big fans of the wonderful, currently-neglected-and-out-of-print Scots author Nicholas Stuart Gray, whose wildly imaginative yet down-to-earth fantasies we both grew up on and both love.

Cassandra says, “I was born in Sydney and grew up reading Hans Christian Andersen, C.S. Lewis and Nicholas Stuart Gray over and over again.” She always knew she wanted to write for young people and had her first book accepted for publication when she was nineteen. Her beautifully-written novels, Clair-de-Lune, The Museum of Mary Child, The Three Loves of Persimmon and Pureheart (2013) are deeply influenced by the worlds of fairytale and 19th century literature.

Cassandra Golds is an Australian writer of children's and YA fantasy: she and I seem to have much in common, not least that we are both big fans of the wonderful, currently-neglected-and-out-of-print Scots author Nicholas Stuart Gray, whose wildly imaginative yet down-to-earth fantasies we both grew up on and both love.

Cassandra says, “I was born in Sydney and grew up reading Hans Christian Andersen, C.S. Lewis and Nicholas Stuart Gray over and over again.” She always knew she wanted to write for young people and had her first book accepted for publication when she was nineteen. Her beautifully-written novels, Clair-de-Lune, The Museum of Mary Child, The Three Loves of Persimmon and Pureheart (2013) are deeply influenced by the worlds of fairytale and 19th century literature.