Who

reigns in fairyland? Many modern fantasies concern themselves with

the fate of doomed but brilliant young men in thrall to a beautiful,

capricious and

often cruel faerie Queen. Often it’s the heroine’s role to try and

rescue the young man, who would be her own boyfriend or lover if only he

were free. Examples are Holly Black’s fantastic ‘Tithe’ and Melissa

Marr's 'Wicked Lovely'.

This particular theme has its

source in the 16th century ballads ‘Tam Lin’, 'Thomas of Ercildoune'

and ‘Thomas the Rhymer’ – especially the former: Janet saves

her lover Tam Lin from the worst possible fate (hellfire) by her bravery

and

single-mindedness. She goes to Miles Cross at midnight and waits for

the Seelie Court to go riding by, seizes Tam Lin from his horse and

holds on to him while he is transformed into a number of horrifying

shapes. At last he appears in his own shape, a naked man, and Janet

casts her cloak around him and claims him as her own true love, while

the furious fairy queen can only threaten and rage.

The story, in which a woman rescues a man, is popular today partly

because we got tired of the stereotype of ‘man rescues woman’. We want

strong women, and in this legend we get double offerings: staunch Janet,

and the powerful Queen of Fays. I was looking for a good picture to

illustrate the modern notion of a fairy queen - vengeful, beautiful,

dangerous - and came across this electrifying photo of Maria Callas as

Medea, taken in Dallas, Texas, 1958. (And yes, Medea is a witch queen

rather than a faery queen, but same difference.)

Of course, a strong heroine doesn’t mean the male characters need to be weak.

Tam Lin in the ballad is far from effeminate – the very first verse warns

maidens to keep away from him, and he rapidly gets Janet pregnant – but let’s

face it, there’s something sexy about a handsome young man in bondage to a

cruel queen, and sexy goes down well in YA fiction… and so we’ve all got used

to it: Faeryland is ruled by a capricious, dangerous queen. And the idea

of the tithe to hell, the sacrifice of the young man, meshes with the figure of

the Corn King or Year King made familiar by Sir James Fraser’s ‘The Golden

Bough’: in a parable of the corn which springs up and dies each year, the

vigorous young king marries the Earth Goddess and is sacrificed at the end of

his short term. (I don't expect many teenagers have ever heard of 'The Golden

Bough', and modern scholars doubt if Corn Kings were ever sacrificed, and in

archeological or anthropological circles, the whole idea has been pretty well

discredited: but it’s a good story and is there in the back of a lot of fantasy

writers’ minds, I'm sure.)

All this is something of a preamble: I want to point out that

fairyland hasn’t always been this way. As far as I can discover - after many years of reading early texts - the all-powerful

Faerie Queen never existed in the popular imagination before the 16th century,

when Queen Elizabeth I was lauded by Edmund Spenser as Gloriana, the Faerie

Queen herself. Prior to that, for centuries upon centuries, in a reflection of

what English people saw about them and regarded as the natural order, Fairyland

was ruled by kings.

|

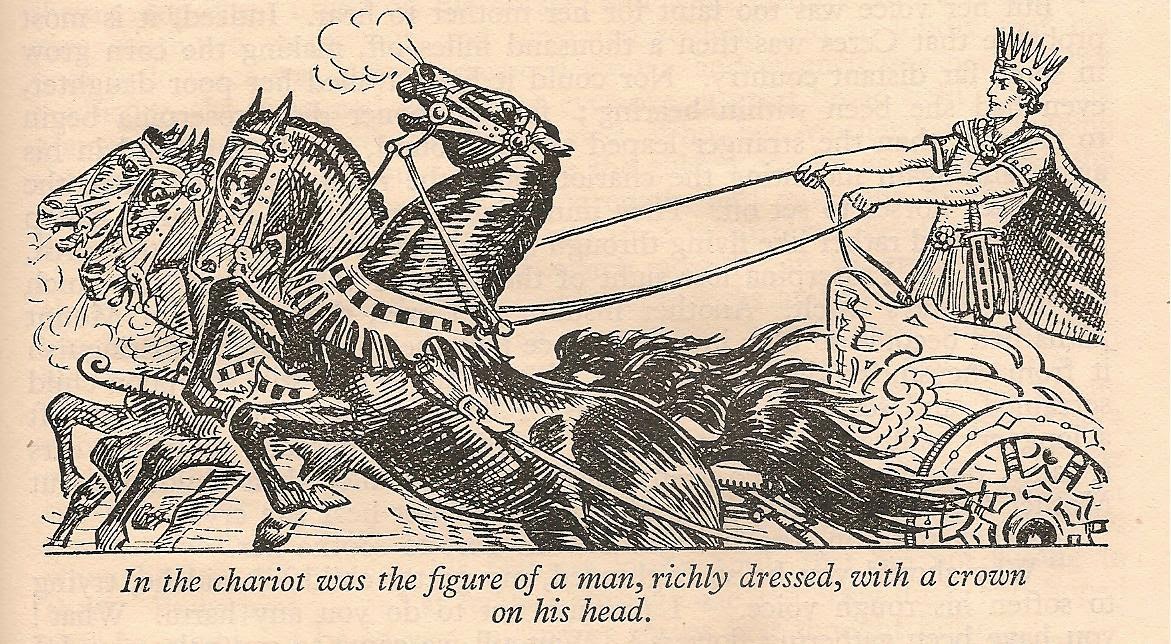

| Pwyll meets Arawn; 19th C. illustration |

The Welsh

Annwn was ruled by King Arawn, whom Pwyll Prince of Dyfed

meets in the Mabinogion.

Annwn is the underworld: the kingdoms of

death and faery are closely blended throughout the early medieval period and

right through into the 16

th century.

After an incident out stag-hunting when the mortal prince Pwyll mistakenly

chases off Arawn’s white-coated, red-eared hounds in favour of his own pack,

he offers Arawn recompense and friendship. In a bargain reminiscent of Gawain’s with

the Green Knight, King Arawn suggests an identity swap:

Pwyll is to take Arawn’s place in his

kingdom, and at the end of the year must face and fight Arawn’s enemy King

Hafgan.

‘I will set thee in Annwn in my stead, and the

fairest lady thou didst ever see I will set to sleep with thee each night, and

my form and semblance upon thee, so that [no man] shall know that thou art not

I. And that,’ said he, ‘till the end of

a year from tomorrow, and our tryst then in this very place.’

‘Aye,’ [Pwyll] replied, ‘though I be there till

the end of the year, what guidance shall I have to find the man thou tellest

of?’

‘A year from tonight,’ said he, ‘there is a tryst

between him and me, at the ford. And be thou there in my likeness,’ said he.

‘And one blow only thou art to give him; he will not survive it. And though he

ask thee to give him another, give it not, however he entreat thee.’

The

Mabinogion, trans. Gwyn Jones, Thomas Jones

Like Gawain, Pwyll is courteous and canny enough to refrain from sexual

intercourse with the beautiful lady, who is of course Arawn’s wife: ‘the moment

they got into bed, he turned his face to the bedside and his back towards her…

not a single night to the year’s end was different from what that first night

was.’ At the end of the year he rides to the ford, meets King Hafgan and

strikes the single blow that fells him ‘with a mortal wound’.

These proofs of faith impress Arawn, and

thenceforth he and Pwyll are constant friends.

In the medieval metrical romance ‘Sir Orfeo’ which blends Celtic and

English fairy lore with the Greek myth of Orpheus, the fairy king is clearly

Pluto, lord of the dead – though he is not named. In the very early Irish tale, ‘The

Wooing of Etain’, the beautiful Etain is stolen away by a fairy king called

Midir. And in a legend related by the 12th century courtier Walter Map, a

British king called Herla is invited to a wedding by an unnamed, goat-footed

pygmy king who rules underground halls of unutterable splendour:

[They] entered a cave in a high cliff, and after

an interval of darkness, passed, in a light which seemed to proceed not from

sun or moon, but from a multitude of lamps, to the mansion of the pigmy. Here

the wedding was celebrated … and when leave was granted, Herla departed laden

with gifts and presents of horses, dogs [and] hawks… The pigmy then escorted

them as far as the place where darkness began, and then presented the king with

a small blood-hound to carry, strictly enjoining him that on no account must any

of his train dismount until that dog leapt from the arms of his bearer… Within

a short space Herla arrived once more at the light of the sun and at his

kingdom, where he accosted an old shepherd and asked for news of his Queen,

naming her. The shepherd gazed at him in astonishment and said: ‘Sir, I can

hardly understand your speech, for you are a Briton and I a Saxon, but they

say… that long ago, there was a Queen of that name over the very ancient

Britons, who was the wife of King Herla; and he, the story says, disappeared in

company with a pigmy at this very cliff, and was never seen on earth again…’

The king, who thought he had made a stay of but

three days, could scarce sit his horse for amazement. Some of his company,

forgetting the pigmy’s orders, dismounted before the dog had alighted, and in a

moment fell into dust. Whereupon the king… warned the rest under pain of a like

fate not to touch the earth before the alighting of the dog. The dog has not yet alighted. And the story

says that this King Herla still holds on his mad course with his band in

eternal wanderings, without stop or stay.

Walter Map, De Nugis Curialium, trans. MR James

Also pygmy-sized is the Fairy King in the French fairy romance ‘Huon of

Bordeaux’: Auberon, a dwarf with the face of beautiful child – whose name

resurfaces in 'A Midsummer Night’s Dream' as Oberon.

Here’s his description in the translation by

Lord Berners, who was Governor of Calais for Henry VIII, and whiled away his

spare time translating French histories and romances into English. The hero of

the tale, Sir Huon, is on his way to Babylon,

when he is warned of the dangers of a magical wood:

You must pass through a wood, sixteen leagues in

length, but the way is so full of magic and strange things that such as pass

that way are lost. In that wood abideth the King of Fairyland named Oberon: he

is but three feet high, and crooked shouldered, but he hath an angelic visage,

so that there is no mortal man that seeth him but that taketh great pleasure in

beholding his face. … He will find the way to speak to you, and if you speak to

him you are lost forever: and you will ever find him before you…

Huon determines to risk the wood, and once under the shade of the trees:

…the dwarf of the fairies, King Oberon, came

riding by, wearing a gown so rich that it were marvel to recount… and garnished

with precious stones whose clearness shone like the sun. He had a goodly bow in

his hand, and his arrows after the same sort, and these had such a property

that they could hit any beast in the world.

Moreover, he had about his neck a rich horn, hung by two laces of gold…

and whosoever heard it, if he were a hundred days journey thereof, should come

at the pleasure of him that blew it. … Therewith the dwarf began to cry aloud

and said, ‘Ye fourteen men that pass by my wood, God keep you all. I desire you

to speak with me, and I conjure you by Almighty God, and by the Christendom

that you have received, and by all that God has made, answer me.’

Hearing the dwarf speak, Huon and his

company…rode away as fast as they were able, and the dwarf was sorrowful and

angry, so he set one of his fingers on his horn, out of which there issued a

wind and a tempest so great that it bore down the trees. …Then suddenly a great

river appeared before them that ran swifter than the birds did fly; and the

water was black and perilous…

Huon of

Bordeax, trans. Lord Berners, retold by R Steele

But this is all enchantment; and when Huon eventually speaks to Oberon, he

wins his friendship and alliance.

These early fairy kings rule over lands which are usually underground, and

there is a pervading sense of loss that hangs about them. Except for

Oberon (who though he claims to be the son of the Lady of the Secret Isle and Julius

Caesar, yet has a place reserved for him in Paradise), they are clearly

pagan kings: there is no sense that they will ever attain to a Christian

heaven.

Their lands are lands of shadow.

Moreover, there’s an interesting hint in all of these stories of

substitution, of succession.

The Wooing of Etain

contains references to identity swaps. In the Mabinogion, Pwyll

becomes Arawn for a whole year, and is

afterwards so closely identified with him in friendship that his name is

changed to ‘Pwyll Head of Annwn’.

(In the 19th century illustration of their meeting, shown above, the artist has made their black and white figures seem like linked opposites, sunlight and shadow, darkness and light.) In Walter Map's 12th century tale, after

visiting the pygmy king’s halls, King Herla finds himself hundreds of years in the

future. He cannot dismount from his horse without crumbling to dust, and

therefore still rides the Welsh border hills at the head of his troop of

knights. The pygmy king vanishes from the tale: in some sense, Herla has

replaced him.

And even in the late medieval

romance of Duke Huon, at Oberon’s death Huon and his wife Esclaramond become

King and Queen of Faeryland (much to the wrath of King Arthur, who hoped to

succeed).

Rudyard Kipling must have read

this romance, it’s behind this fabulous piece of writing in his story ‘Weland’s

Sword’ in

Puck of Pook’s Hill:

“Butterfly wings, indeed! I’ve seen Sir Huon and

a troop of his people setting out from Tintagel Castle

for Hy-Brasil in the teeth of a sou-westerly gale, with the spray flying all

over the Castle, and the Horses of the Hills wild with fright. Out they’d go in a

lull, screaming like gulls, and back they’d be driven five good miles inland

before they could come head to wind again. Butterfly wings! It was Magic –

Magic as black as Merlin could make it, and the whole sea was green fire and

white foam with singing mermaids in it. And the Horses of the Hills picked

their way from one wave to another by the lightning flashes. That was how it was in the old days!”

And in its companion story ‘Cold Iron’, from

Rewards and Fairies, Puck tells the children about ‘Sir Huon of Bordeaux – he succeeded

King Oberon.

He had been a bold knight

once, but he was lost on the road to Babylon,

a long while back…’

There it is again, you see? - that hint of loss in all these stories.

In a tale called ‘The Sons of the Dead

Woman’, Walter Map tells of a Breton knight who buried his wife and then saw

her one evening dancing in a gloomy valley, in a ring of maidens. When the

fairy king steals Orfeo’s wife, she is mourned as dead. And yet, tantalisingly,

the dead may not

be dead, but stolen

away into some other dimension, some fairy realm of half-existence. This is the

fantasy of grief. And of course time runs differently there: if you visit, you

risk losing yourself forever.

This 12th century fairyland, the mysterious underground kingdom of the dead

or half-dead, is the fairyland I wrote about in my book ‘Dark Angels’ (The

Shadow Hunt’ in the USA).

One of the characters, the troubadour knight Lord Hugo, lost his wife seven

years before the book opens.

“The

night she died – it was New Year’s Eve, and the candles burned so low and blue,

and we heard over and over again the sound of thunder. That was the Mesnie

Furieuse – the Wild Host – riding over the valleys. Between the old

year and the new, between life and death – don’t you think, when the soul is

loosening from the body, the elves can steal it?”

So I sent my young hero Wolf searching for Hugo's lost wife through the

cramped tunnels of the old lead mines under the local mountain, Devil's Edge,

to confront the lord of the underworld himself: with unexpected

consequences, as this trailer for the book suggests.

Picture credits: Huon of Bordeaux illustrations by Fred Mason, 1895

.jpg)