I have made a discovery,

or at least a possible discovery. Maybe others have made it before, but

it is new to me: in 1891 at the age of seventeen G.K. Chesterton, then a pupil

at St Paul’s School London, wrote and illustrated a witty natural history (or supernatural

history?) of devils, which he called ‘Half-Hours In Hades: An Elementary

Handbook of Demonology’. It opens with a preface by the supposed author, a ‘Professor

of Supernatural Science’:

In the autumn of 1890, I was leaving the Casino at Monte Carlo in company wth an eminent Divine, whose name, for obvious reasons, I suppress. We were engaged in an interesting discussion on the subject of Demons, he contending that they were an unnecessary, not to say prejudicial, element in our civilisation, an opinion which, needless to say, I strongly opposed. Having at length been so fortunate as to convince him of his error, I proceeded to furnish him with various instances in which Demons have proved beneficial to mankind, and at length he exclaimed, ‘My dear fellow, why do you not write a book about – ’ Here he coughed. The idea took so strong a hold upon me that from that time I have taken careful note of the the habits and appearance of such specimens as come in my way, and my studies have resulted in the production of this little work, which will, I trust, prove not uninteresting to the youthful seeker after knowledge.

With its casually

ludicrous opening in which a professor and a clergyman exit the Casino at Monte

Carlo deep in a discussion about demons, and its spoof faux-academic style, this

is a polished piece of writing from a boy of seventeen. Daring, too, especially when the

so-called Professor goes on to dedicate his work to – well, to Lucifer:

In my capacity as Professor of Supernatural Science at Oxford University, it has often been my duty to call upon an individual who probably knows more about all branches of the subject with which I am about to deal than any man on earth, although no one has yet persuaded him to give his knowledge to the world, and with his permission I have dedicated these pictures to him, as some slight recognition of the wisdom and experience which he has brought to my assistance in the compiling of this modest treatise.

The word ‘cimmerian’ being

unknown to me (see above), I looked it up in the Shorter Oxford Dictionary, which provides

the meaning: ‘Of or belonging to the Cimmerii, a people fabled by the ancients

to live in perpetual darkness. Hence, an epithet of dense darkness.’ Where young Chesterton came across it I don’t know but lo! the rewards of a classical education. He went on to write three

‘chapters’ of this short but lively treatise. The first and longest concerns

‘The Five Primary Types’ of demons and their habits:

For those who love the study of Demonology (and I pity the man or woman who does not) it possesses an interest which will remain after health, youth and even life have departed.

I love the sinister, dead-pan humour of this assertion, delivered as though demonology were a hobby as ordinary as stamp-collecting. Chesterton, or his professor, now introduces us to ‘The Common (or “Garden”) Serpent ... so-called because its first appearance in the world took place in a Garden. Since that time its proportions have dwindled considerably, but its influence and power have largely increased; it is found in almost everything.’

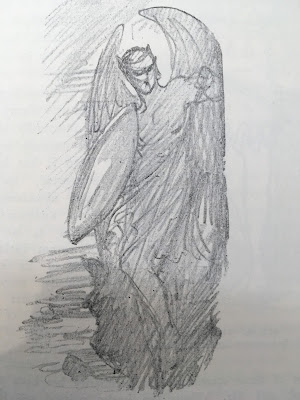

Beside it comes the Mediaeval

Demon, ‘whose horns, tail and claws form a remarkable contrast to the

serpentine formation of the first type.’

It is ... the subject rather of playfulness and household merriment rather than abhorrance, while the far cleverer and more graceful serpent is the object of a cruel and unreasoning persecution. But useful as the mediaeval species is found at the present day as a general source of amusement, it has of late somewhat failed to stir public interest, which is turned towards newer and more elegant varieties. Mr. J. Milton, in his interesting and valuable work on this subject, has discussed at some length the leading characteristics of a fine species of which he was primarily the discoverer... This magnificent animal measures at least four roods, and when floating full length on the warm gulf, of which it is an inhabitant, has been compared by its discoverer to a whale.*

You get the picture. Accounts of the ‘Red Devil’ (Diabolus Mephistopheles), and the ‘Blue Devil’ (Caerulius Lugubrius) follow, while Chapter 2, ‘The Evolution of Demons’ is comprised mainly of cartoons (Chesterton’s inventive powers perhaps temporarily exhausted). Here they are:

Chapter 3, ‘What We

Should All Look For’, is a dialogue between mother and child which begins,

‘But, mamma, can we all see devils?’ – ‘Certainly, Charlotte, if we take the

trouble’ – and ends with a lesson in which 'Mamma' demonstrates how to

raise a demon from a cauldron.

‘Do you see those two round green orbs of light, Jane? ... Do not scream, Charlotte, for that would be very naughty, and would perhaps frighten the little creatures, as they are very timid. By this time, children, you may perceive the outline of an attenuated figure, resembling in some respects that of a skeleton, though the ears, which you can now see moving, show that this is not the case. Lift little Harry up, James, since he is too small to see over the edge of the cauldron.’

I don’t know for sure but would guess that Chesterton probably wrote ‘Half-Hours in Hades’ to amuse his fellow schoolboys, but years later he considered it strong enough to deserve inclusion in his collection of stories and essays ‘The Coloured Lands’ (Sheed & Ward, 1938), and I think he was right. It is daring, funny and satirical, as when ‘mamma’ tells her child that the vicar, Dr. Brown, is the proud owner of a varied collection of demons.

‘But, mamma’ [the child asks] ‘does Dr Brown love his little pets?’ – ‘I have reason to believe that he is fondly attached to them. They are never out of his sight and he has often said that he has gleaned many useful lessons from their habits. In fact he says that he would not be the man he is but for them, and one glance at Dr. Brown will make it clear this is no exaggeration.’

You may agree with me by now that Half-Hours in Hades in some ways resembles C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters which, though written 50 years later, employs much the same kind of satire and dead-pan humour. In Letter XV, for example, Screwtape describes two churches he considers suitable for the damnation of his nephew Wormwood’s ‘patient’:

I think I warned you before that if your patient can’t be kept out of the Church, he ought at least to be violently attached to some party within it. I don’t mean on really doctrinal issues; about those, the more luke-warm he is the better. … The real fun is working up hatred between those who say ‘mass’ and those who say ‘holy communion’ when neither party could possibly state the difference between, say, Hooker’s doctrine and Thomas Aquinas’, in any form that would hold water for five minutes.

And in Lewis's introduction to the letters – ‘I have no intention of explaining how the correspondence which I now offer to the public fell into my hands’ – his pretence of their extraneous diabolic origin echoes the claim of Chesterton’s ‘professor’ to have gathered his knowledge from the Authority on that subject.But

did Lewis ever actually read Half-Hours in Hades? According to a letter written Sunday

July 21, 1940 to his brother Warnie, the idea of a correspondence between devils

occurred to him in church:

Before the service was over – one could wish these things came more seasonably – I was struck by an idea for a book which I think might be both useful and entertaining. It would be called ‘As one Devil to Another’ ... the idea would be to give all the psychology of temptation from the other point of view...

His biographers Roger Lancelyn Greene and Walter Hooper record that when Hooper once asked ‘if there were any book which had given him the idea for The Screwtape Letters,’ Lewis showed him one I have never heard of, Confessions of a Well-Meaning Woman by Stephen McKenna (1922) in which (as Lewis explained) the same moral inversion occurs, along with ‘the humour which comes of speaking through a totally humourless person.’ He did not mention Chesterton as any kind of inspiration. All the same, Lewis read many of Chesterton’s works, including his essays, and Christian apologetics such as Orthodoxy (1908) and The Everlasting Man (1925), praising the latter as ‘the best popular defence of the full Christian position I know.’

Though Chesterton was more than twenty years Lewis’s senior, the two men had plenty in common. Both wrote popular novels and poetry as well as essays and theology, and both filtered Christianity through the mesh of fiction. Chesterton’s ‘Father Brown’ detective tales are concerned with sin and repentence, justice, mercy and the love of God. Lewis’s Narnia stories introduce the same concerns to a younger audience. Both men were fluent, charismatic writers blessed with the ability to communicate, a sense of humour and the common touch. Chesterton delivered a series of radio lectures for the BBC in the 1930s; Lewis did the same during the war years. As a writer and a public figure, Chesterton was impossible to miss; and it is not unlikely that Lewis might have obtained a copy of the The Coloured Lands when it came out in 1938, and enjoyed Half-Hours in Hades, Chesterton’s jeu d’esprit.

If he had though, wouldn’t he have said? First, he might simply have forgotten: he was a busy man with a lot going on. The

Screwtape Letters were originally published one per week from May to

November 1941 in a High Church periodical, The

Guardian (not the newspaper, then known as The Manchester Guardian); Lewis donated the £2 fee for each

installment to a fund for the widows of clergymen. He had begun his wartime

broadcasts on ‘Mere Christianity’ and was writing Voyage to Venus (Perelandra), plus the lectures on Milton which

subsequently became A Preface to Paradise

Lost. Child evacuees had arrived at his Oxford home, The Kilns, and he was

still actively tutoring students. Second, The

Screwtape Letters has psychological depth

beyond the reach of the teenage Chesterton, and a structure and purpose

that Half-Hours in Hades lacks. Writers borrow all the time; they cannot credit all their sources, and G.K.

Chesterton’s reputation did not depend on a piece of clever but ultimately inconsequential juvenilia. Did it once sow a seed in Lewis's imagination? We may never know, but the possibility is fascinating.

* Thus Satan, talking to his nearest mate,

With head uplift above the wave, and eyes

That sparkling blazed; his other parts besides

Prone on the flood, extended long and large,

Lay floating many a rood, in bulk as huge

As whom the fables name of monstrous size,

Titanian or Earth-born, that warred on Jove,

Briareos or Typhon, whom the den

By ancient Tarsus held, or that sea-beast

Leviathan, which God of all his works

Created hugest that swim th’ ocean-stream.

Paradise Lost, Book 1

Picture credits:

All artwork by G.K. Chesterton.