Poetry – I love the stuff – I have masses of it by heart –

but once in a while it’s fun to be a little irreverent, don’t you think? A few days ago, I found myself chanting

William Morris’s sonorous ‘Two red roses across the moon’ – like this –

There was a lady lived in a hall

Large in the eyes and slim and tall,

And ever she sung from noon to noon,

Two red roses across

the moon.

–

and suddenly caught myself snorting.

There was a knight came riding by

In early spring, when the roads were dry;

And he heard that lady sing at the noon,

Two red roses across

the moon.

The lady had clearly been infected with an ear worm. Through the entire poem, these are the only

words she – compulsively – speaks. The

knight catches it too; he spurs off to battle:

You scarce could see for the scarlet and blue,

A golden helm or a golden shoe,

So he cried, as the fight grew thick at the noon,

Two red roses across the moon!

Inspired by the lady’s song, the knight and his gold side win:

Verily then the gold won through

The huddled spears of the scarlet and blue,

And they cried, as they cut them down at the noon

Two -

- but you got it. After which, the knight and the lady get

together. I wonder how their domestic

life went?

“Pass the salt, dear.”

“Two red roses across the moon.”

It’s utterly ludicrous, and I don’t know why it works, but

in its faux-medieval, stained-glass, Pre-Raphaelite way, it actually does. I may smile.

But I like it.

Maybe it’s a grace of the Victorian era, that they didn’t

mind being totally, and I mean totally

over the top? And now we’re all too self

conscious and expect poetry to be a lyrical baring of the soul and take itself seriously, for heavens

sake? In which case, what do we make of

this?

But the Raven still beguiling all my fancy into smiling,

Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird, and

bust, and door,

Then upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking

Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore –

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt and ominous bird of

yore

Meant in croaking “Nevermore.”

Now the normal human reaction would be for Poe to jump up

screaming “Oh my god, a huge bird just flew in at my window!” and rush for a

broom or something, to try and prod it out.

But Poe the narrator isn’t normal, he’s a Victorian Gothic poet, and he

sees at once that the Raven is a supernatural portent – and he’s comfortable

enough with that idea to pull up a

velvet cushion and sit trying to work it all out.

Thus I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing

To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom’s

core;

This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining

- at ease, mark you, at ease! -

On the cushion’s velvet lining that the lamplight gloated

oe’r,

But whose velvet violet lining with the lamplight gloating

o’er

She shall press,

ah, nevermore.

I doubt if any modern poet would dare to introduce a ‘fowl

with fiery eyes’ into a serious poem; and those elaborate feminine internal

rhymes are incredibly dangerous and could topple the poem over into absurdity

at any moment. Poe must know this! But

he has nerves of steel and keeps his balance.

You’ll notice a common element of these two poems: the

refrain. Refrains – I would venture

– have gone out of fashion. Here’s another brilliant Victorian poem which

employs one. By Longfellow, this time:

The shades of night were falling fast

When through an Alpine village passed

A youth, who bore, mid snow and ice,

A banner with a strange device,

Excelsior!

Well, there you go.

His brow was sad; his eye beneath

Flashed like a falchion from its sheath,

And like a silver clarion rung

The accents of that unknown tongue,

Excelsior!

While Morris's ‘red roses’ lady was stuck in her

castle, the similarly afflicted youth sets out across the mountains – a

bit of stereotyping going on there, I fear – but anyway, like the lady,

Longfellow’s youth has no other conversation going.

“Oh stay,” the maiden said, “and rest

Thy weary head upon this breast!”

A tear stood in his bright blue eye,

But still he answered, with a sigh,

Excelsior!

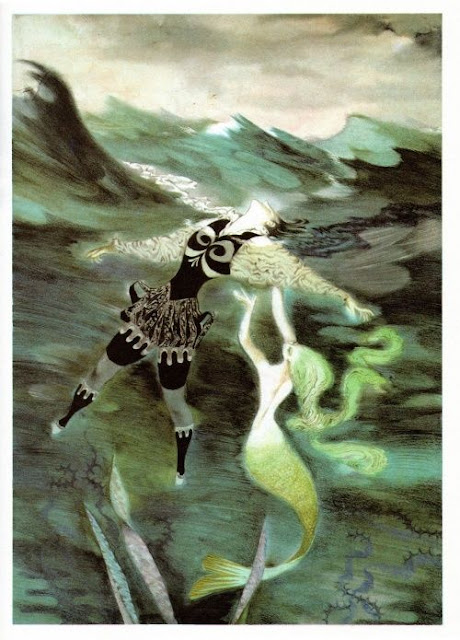

James Thurber’s illustrations demonstrate that he, too,

couldn’t resist the unintentionally comic side of all this.

“Beware the pine tree’s withered branch!

Beware the awful avalanche!”

This was the peasant’s last Goodnight,

A voice replied, far up the height,

Excelsior!

But of course the mysterious youth perishes. Here he lies dead in the snow, surrounded by

the monks of St Bernard and one of Thurber’s lugubrious dogs:

A traveller, by the faithful hound

Half-buried in the snow was found,

Still grasping, in his hand of ice,

That banner with the strange device,

Excelsior!

There in the twilight cold and gray,

Lifeless, but beautiful he lay,

And from the sky, serene and far,

A voice fell like a falling star:

Excelsior!

As for the hounds of spring, they of course come from the

Chorus from 'Atalanta in Calydon', by that

most over-the-top of all Victorian poets, Charles Algernon Swinburne – and here he is, in full throated ease:

When the hounds of spring are on winter’s traces,

The mother of months in meadow or plain

Fills the shadows and windy places

With lisp of leaves and ripple of rain;

And the brown bright nightingale amorous

Is half assuaged for Itylus

For the Thracian ships and the foreign faces

The tongueless vigil, and all the pain.

Yes, he assumes we know a lot about Greek myths, but why

shouldn’t he? And even if we didn’t, how

beautiful is this?

For winter’s rains and ruins are over,

And all the season of snows and sins

The days dividing lover and lover,

The light that loses, the night that wins;

And time remembered is grief forgotten,

And frosts are slain and flowers begotten

And in green underwood and cover

Blossom by blossom the spring begins.

I admire the Victorians.

I admire their passion, their sensitivity and their love of beauty, and

I really don’t care if they are sometimes a bit over the top and make me smile

– and I don’t think they’d care either.

We need more moments of unguarded passion in our

lives - and less caution and cynicism...

I’m off on holiday for a couple of weeks. Enjoy the summer!

Picture credits: James Thurber, 'The Thurber Carnival', Penguin 1965