A very long time ago in

my late teens, I wrote a book with the rather unimaginative title ‘The Magic

Forest’ which was (quite rightly) never published. Although derivative (I was inspired

by Walter de la Mare’s strange and wonderful novel ‘The Three Royal Monkeys’)

it was nevertheless the closest I’d yet got to finding my own voice; and I’d

been writing lengthy narratives ever since nine or ten years old. It was a

dream-quest story in which a girl goes through a picture into a magical world:

the picture in question was a reproduction of

Henri Rousseau’s ‘The Snake-Charmer’ which hung on my bedroom wall (see above). My

heroine, Kay, looks at it and sees

...the ripples of a lake reflecting the quick luminous afterglow of a sun’s sinking. There were night-flowering reeds and a tall, heron-like bird, and standing in the darkness of the trees, partly in silhouette against the night sky, was a human figure. It was wearing a dark cloak and piping on a flute. Answering the flute came snakes, great forest pythons pouring scarcely distinguishable from the branches and from the lake. Kay’s feet sank into shallow mud. She heard the low, hollow-sweet notes, saw the snakes twist about the charmer’s legs. A heavy, scaly body dragged over her foot. Midges stung and bit her, but a little coolness came breathing over the water.

And so begins an adventure which I won’t bore you with, it's enough to say that Kay goes on a

quest with a yellow water-bird and a monkey, to find a sorcerer who has infested

the forest with poisonous butterflies.

I knew that ‘going into a picture’ was not an original idea

but one which had appeared in several of my favourite children’s books. In C.S.

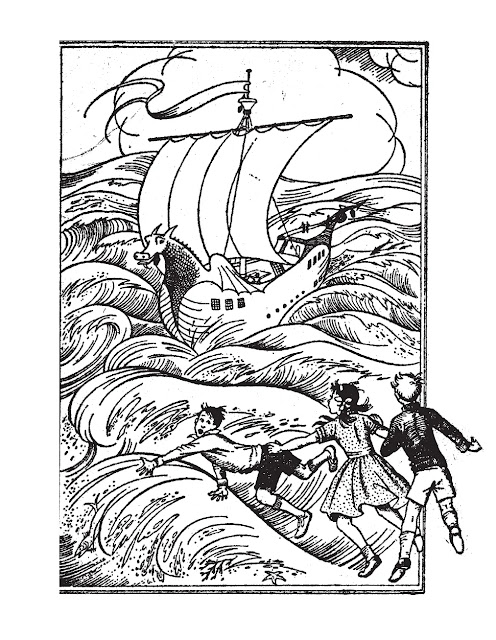

Lewis’s ‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’ (1952) Lucy and Edmond Pevensie, and

their cousin Eustace Scrubb, tumble into a painting of what looks like a

Narnian ship at sea. When Eustace asks Lucy why she likes it, she replies, ‘because the ship looks as if it was really moving. And the water looks as if

it was really wet. And the waves look as if they were really going up and down.’

She’s right, they are doing these

things. The ship rises and falls over the waves, a wind blows into the room

bringing a ‘wild, briny smell’, and ‘Ow!’ they all cry, for ‘a great, cold,

salt splash had broken right out of the frame and they were breathless from the

smack of it, besides being wet through.’ As Eustace rushes to smash the painting

the other two try to pull him back. Next moment all three are struggling on the

edge of the picture frame, and a wave sweeps them into the sea.

Lewis didn’t invent the ‘picture as portal’ trope, either.

It’s quite likely he found it in a Japanese tale, ‘The Story of Kwashin Koji’ from

‘Yasō-Kidan’ (‘Night-Window Demon Talk’), a book of legends collected by

Ishikawa Kosai (1833-1918) and retold by Lafcadio Hearn in his 1901 book ‘A

Japanese Miscellany’. It is the sort of thing Lewis would have read. It tells

of Kwashin Koji, a rather disreputable old fellow and a heavy drinker, who made

a living ‘by exhibiting Buddhist pictures and by preaching Buddhist doctrine.’

On fine days he would hang a large picture – ‘a kakemono on which were depicted

the punishments of the various hells’ – on a tree in the temple gardens and

preach about it. The painting was so wonderfully vivid that onlookers were

amazed.

Hearing

this, the ruler of Kyōto, Lord Nobunaga, commanded Kwashin Koji to bring it to

the palace where he could view it. The old man obliged and Nobunaga was deeply impressed

by the painting. Noticing this, his servant suggested that Kwashin should offer

it as a gift to the great lord. Since his livelihood depended upon the picture,

Kwashin asked instead for payment in gold, which was refused. So he rolled up the

picture and left. But the servant followed him, killed him, and took the picture

for his lord. When the scroll was unrolled, however, it was found to be completely

blank – while Kwashin had mysteriously returned to life and was showing his

picture in the temple grounds as before. Some time later Nobunaga was himself murdered

by Mitsuhidé, one of his captains, who invited Kwashin Koji to the palace, feasted

him and gave him plenty to drink. The old man then pointed to a large folding

screen which depicted ‘Eight Beautiful Views of the Lake of Omi’, and said, ‘In

return for your august kindness, I shall display a little of my art’. Far off in

the background, the artist had painted a man rowing a boat, ‘occupying, upon

the surface of the screen, a space of less than an inch in length.’ As Kwashin

Koji waved his hand, everyone in the room saw the boat turn and begin to approach

them. It grew rapidly larger...

And all of a sudden, the water of the lake seemed to overflow out of the picture into the room, and the room was flooded; and the spectators girded up their robes in haste as the water rose above their knees. In the same moment the boat appeared to glide out of the screen, and the creaking of the single oar could be heard. Then the boat came close up to Kwashin Koji, and Kwashin Koji climbed into it; and the boatman turned about, and began to row away very swiftly. And as the boat receded, the water in the room began to lower rapidly, seeming to ebb back into the screen... But still the painted vessel appeared to glide over the painted water, retreating further into the distance and ever growing smaller, till ... it disappeared altogether, and Kwashin Koji disappeared with it. He was never again seen in Japan.

The lakewater flooding

out of the painted screen corresponds to the ‘great salt splash’ of the wave bursting

into the children’s bedroom in ‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’, while the

creaking oar finds an echo in Lewis’s description of ‘the swishing of waves and

the slap of water against the ship’s sides and the creaking and the overall

high steady roar of air and water’.

John Masefield’s ‘The Midnight Folk’ (1927), and its sequel ‘The Box of Delights’ (1935) contain some delightful ‘pictures as portals’. In ‘The Midnight Folk’ little Kay Harker, left by his governess to learn the verb ‘pouvoir’, looks up as the portrait of his great-grandpapa comes to life:

As Kay looked, great-grandpapa Harker distinctly took a

step forward, and as he did so, the wind ruffled the skirt of his coat and

shook the shrubs behind him. A couple of blue butterflies which had been upon

the shrubs for seventy odd years, flew out into the room. ... Great-grandpapa

Harker held out his hand and smiled... “Well, great-grandson Kay,” he said, “ne

pouvez vous pas come into the jardin avec moi?” [....]

Kay jumped on to the table; from there, with a step of run, he leaped on to the top of the fender and caught the mantelpiece. Great-grandpapa Harker caught him and helped him up into the picture. Instantly the schoolroom disappeared. Kay was out of doors standing beside his great-grandfather, looking at the house as it was in the pencil drawing in the study, with cows in the field close to the house on what was now the lawn, the church, unchanged, beyond, and, near by some standard yellow roses, long since vanished, but now seemingly in full bloom.

His great-grandfather

takes him into the house, where ‘A black cat, with white throat and paws, which

had been ashes for forty years, rubbed up against great-grandpapa’s legs and

then, springing on the arm of his chair, watched the long-dead sparrows in the

plum tree which had been firewood a quarter of a century ago’. This beautifully

gentle transition into the past as

well as into a painting is something I’ve always loved: it depicts time past with

yearning but without melancholy, and we see little orphaned Kay receive care

and support from kind ancestors who watch over him. Exciting as it is, ‘The

Midnight Folk’ is a book a child can read and never feel unsafe. Later in the story,

Kay realises that his governess is really a witch, and his grandmother’s

portrait addresses him.

“Don’t let a witch take charge at Seekings. This is a house

where upright people have lived. Bell her, Kay; Book her, boy; Candle her,

grandson; and lose no time: for time lost’s done with, but must be paid for.”

He looked up

at her portrait, which was that of a very shrewd old lady in a black silk

dress. She was nodding her head at him so that her ringlets and earrings shook.

“Search the wicked creature’s room,” she said, “and if she is, send word to the Bishop at once.”

“All right,” Kay said, “I’ll go. I will search.”

This time Kay doesn’t

enter the picture, but his grandmother’s words give him strength, confidence

and purpose.

A

string of pack mules descend the mountain path, and near the end of the line trots

a white mule with a red saddle.

The first mules turned off at a corner. When it came to the

turn of the white mule to turn, he baulked, tossed his head, swung out of the

line, and trotted into the room, so that Kay had to move out of the way. There

the mule stood in the study, twitching his ears, tail and skin against the

gadflies and putting down his head so that he might scratch it with his hind

foot. “Steady there,” the old man whispered to him. “And to you, Master Kay, I

thank you. I wish you a most happy Christmas.”

At that, he swung himself onto the mule, picked up his theatre with one hand, gathered the reins with the other, said, “Come, Toby,” and at once rode off with Toby trotting under the mule, out of the room, up the mountain path, up, up, up, till the path was nothing more than a line in the faded painting, that was so dark upon the wall.

One of the many reasons

this passage works so well is its detailed physicality, the realistic animal

behaviour of the mule quivering its skin and scratching its head and taking up

so much room in the study. And as magic, it’s such a satisfactory way to foil the baddies.

Towards

the end of the book, Kay has ‘gone small’ via the magic of the Box of Delights

but having temporarily lost the Box he cannot restore himself to his proper

size. Finding Cole Hawlings chained and caged in the underground caverns which

Abner Brown is about to flood, he creeps into Cole’s pocket for a bit of lead

pencil and a scrap of paper on which to draw, at Cole’s request, ‘two horses

coming to bite these chains in two’. Though plagued by the snapping jaws of

little magical motor-cars and aeroplanes, he manages to draw the horses rather

well.

The drawings did stand out from the paper rather strangely.

The light was concentrated on them; as he looked at them the horses seemed to

be coming towards him out of the light; and no, it was not seeming, they were

moving; he saw the hoof casts flying and heard the rhythmical beat of hoofs. The

horses were coming out of the picture, galloping fast, and becoming brighter and

brighter. Then he saw that the light was partly fire from their eyes and manes,

partly sparks from their hoofs. “They are real horses,” he cried. “Look.”

It was as

though he had been watching the finish of a race with two horses neck and neck

coming straight at him... They were two terrible white horses with flaming

mouths. He saw them strike great jags of rock from the floor and cast them,

flaming, from their hoofs. Then, in an instant, there they were, one on each

side of Cole Hawlings, champing the chains as though they were grass, crushing

the shackles, biting through the manacles and plucking the iron bars as though

they were shoots from a plant.

“Steady there, boys,” said Cole...

Cole places the

diminutive Kay on one of the horses and leads them along the rocky corridor,

but the water is coming in fast. ‘Draw me,’ says Cole, ‘a long roomy boat with

a man in her, sculling her’ and ‘put a man in the boat’s bows and draw him with

a bunch of keys in his hand.’ Kay does his best, although the man’s nose is ‘rather

like a stick’, and Cole places the drawing on the water. It drifts away while

the stream becomes angrier and more powerful.

“The sluice-mouth has given way,” Kay said.

“That is

so,” Cole Hawlings answered. “But the boat is coming too, you see.”

Indeed, down the stream in the darkness of the corridor, a boat was coming. She had a light in her bows; somebody far aft in her was heaving at a scull which ground in the rowlocks. Kay could see and hear the water slapping and chopping against her advance; the paint of her bows glistened above the water. A man stood above the lantern. He had something gleaming in his hand: it looked like a bunch of keys. As he drew nearer, Kay saw that this man was a very queer-looking fellow with a nose like a piece of bent stick.

With its boatman, boat,

creaking oar and rush of oncoming water, this too is very reminiscent of the

tale of Kwashin Koji, which I suspect Masefield as well as Lewis may have read.

Whether it’s so or not, both the concept and the writing are wonderful.

A novel

which owes nothing to the Japanese story is Meriol Trevor’s ‘The King of the

Castle’ (1966). A decade on from C. S. Lewis but largely forgotten today,

Trevor’s books for children were well-written and sometimes powerful fantasies

with allegorical Christian themes. I would borrow them from the local library, and enjoyed them.. They were less popular among children than

Lewis’s books, probably because Trevor’s ‘Christ’ figures were human adults, where

Lewis had a glorious golden lion. They follow in general the pattern of

‘contemporary children find a way into magical worlds and go on quests’; her

best book is (I think) ‘The Midsummer Maze’, but ‘The King of the Castle’ is good too. It opens

with a boy, Thomas, sick in bed (see mysterious

illnesses that keep children marooned in bed for weeks). Slowly recovering from

whatever it was, he grows bored, so one day his mother gives him a gilt-framed picture

she bought in a junk shop, so that he will ‘have something to look at instead

of the wallpaper’. This feels a bit forced; would a young boy really appreciate

‘an old engraving in the romantic style’? But perhaps the castle swings it:

It showed a wild rocky landscape with twisted thorn trees on the horizon, bent by years of gales, and a few sheep prowling on the thin grass near a torrent which rushed turbulently out of a deep and shadowy ravine. Beside the river a road ran, white in the darkness, till it too disappeared behind the steep shoulder of the gorge. Perhaps it led on to the castle which backed against a wild and stormy sky of clouds that rolled like smoke over the sombre hills.

Thomas thinks it ‘very

mysterious’ and once it’s on the wall he lies looking at it.

He wondered where the road went after it turned the corner.

He imagined himself walking along the road, rutted and dusty, stony as it was.

The huge cliffs loomed above him.

“But I am walking along the road,” Thomas thought suddenly. He looked down and saw his feet walking. They wore brown leather rubber-soled shoes. He was not wearing pyjamas but jeans and his thick sweater, but the wind seemed to cut through the wool. It was cold.

Following the road up

beside the rushing river, he turns to look back, wondering if he will see his

bedroom with himself lying in bed. But ‘what he saw was the wild country of the

picture extended backwards, the river running away and away towards

thick-forested hills. It was almost more unnerving to find himself totally in

the world of the picture.’ I like this acknowledgment of the unsettling side of suddenly entering an unknown world. Soon after, a young shepherd and his dog rescue Thomas from a wolf. The shepherd turns out to be this book’s Christ figure,

and at the end of the story Thomas returns through the picture to find himself

back in bed.

Compared with with the other ‘paintings as portals’ discussed here, this is perhaps the weakest, since Thomas’s interaction with the engraving is entirely passive. It’s given to him and he doesn’t even need to leave his bed: just looking at it does the job. Characters in the other stories all have some degree of agency in passing through the portals. Kwashin Koji is in full control of what happens: he can enter a painting at will. Lucy and Edmund topple into the Eastern Sea while actively trying to prevent Eustace breaking the picture. Accepting his great-grandfather’s invitation, Kay Harker clambers on to the mantelpiece to reach him. Like Kwashin Koji, Cole Hawlings chooses a painting to enter and escape through, while the rather older Kay Harker of ‘The Box of Delights’ draws the pictures which come to life and rescue them. (Do these drawings count as portals? While it’s true that Kay and Cole don’t pass through them, the horses, boats and boatmen emerge from the paper into this world, so I think they do.)

Kay’s

drawings of horses and boatmen bring me to the drawings in Catherine Storr’s

wonderfully sinister ‘Marianne Dreams’ (1958). Marianne is another child struck

down by an unnamed illness that keeps her in bed. Weeks on, bored and convalescent,

she finds a stub of pencil in an old work-box and uses it to draw a house with

four windows, a door and a smoking chimney – to which she adds a fence, a gate

and a path, a few flowers, ‘long scribbly grass’ and some rocks. Then she falls

asleep and dreams she’s alone in a vast grassland dotted with rocks. Walking towards

a faint line of smoke she arrives at a blank-eyed house with ‘a bare front

door’ ringed with an uneven fence and pale flowers. A cold wind springs up and

she’s frightened. ‘I’ve got to get away from the grass and the stones and the

wind. I’ve got to get inside.’

Marianne’s

dreams take her into the inimical ‘world’ of her drawing: what she finds there

depends on whatever she has recently drawn, plus the mood in which she drew it. The experience is uneasy from the start and becomes scarier at every visit. It’s

arguable that the drawings (to which she keeps adding) are not portals at all, only

the catalyst for dreams which express Marianne’s anger, fear and stress. Nevertheless

the strange ‘country’ in which she finds herself – and to a certain extent manipulates

– feels psychologically serious and real; portals may work in more than one

way. She draws a boy looking out of the window, someone who can let her into

the house. Next night he is there. She discovers that his name is Mark: he is

real, very ill and unable to walk, and shares with her the same nice home

tutor. In the dream world he is dependent on her: as the wielder of the pencil

she can draw things for his comfort – or not. In a fit of temper one day she scribbles

thick black lines, like bars, all over the window where he sits – raises the

fence, adds more stones in a ring around the house and gives to each one a

single eye. All these horrifying things become real in her next dream.

Marianne looked round the side of the window. From where

she stood she could see five – six – seven of the great stones standing

immovable outside. As she looked there was a movement in all of them. The great

eyelids dropped; there was a moment when each figure was nothing but a hunk of

stone, motionless and harmless. Then, together, the pale eyelids lifted and

seven great eyeballs swivelled in their stone sockets and fixed themselves on

the house.

Marianne screamed. She felt she was screaming with the full power of her lungs, screaming like a siren: but no sound came out at all. She wanted to warn Mark, but she could not utter a word. In her struggle she woke.

As the terrifying stone

Watchers crowd ever closer to the house, Marianne and Mark must escape.

Marianne draws hills in the distance behind the house, with a lighthouse

standing on them, for she knows the sea there, just out of sight. Eventually

the children make it to the lighthouse on bicycles she has drawn. Here they are

safe, but Mark points out that they can’t stay forever. They must reach the

sea, inaccessible below high cliffs. A helicopter is needed, but Marianne

cannot draw helicopters. After struggling with herself to relinquish power (‘it’s

my pencil!’) she draws the pencil

into the dream so that Mark can have it. He draws a helicopter which arrives

before Marianne can dream again, but leaves a message promising to make it come

back for her: in the end trust prevails.

Everything seemed to be resting; content; waiting. Mark

would come: he would take her to the sea. Marianne lay down on the short,

sweet-smelling turf. She would wait, too.

‘Marianne Dreams’ can be genuinely frightening, nightmarish even; but the children’s bickering yet supportive friendship enlivens the story and makes it accessible to young readers.

Lastly, I cannot resist mentioning James Mayhew’s much-loved

and utterly charming series of picture-books which introduce younger children

to art. ‘Katie’s Picture Show’ was the first, published in 1989 and followed by

several others in which little Katie jumps into various famous paintings, meets

the characters and has age-appropriate adventures.

Pictures, especially representative pictures, are like windows. We simultaneously look at them and through them. John Constable’s ‘The Cornfield’ lures the viewer in, past the young boy drinking from the brook, past the panting sheepdog and the donkeys under the bushes, past the reapers busy in the yellow corn, and on towards the far horizon. In imagination we enter not only the picture but also the long-departed past of 1820s Suffolk – in much the same way as little Kay Harker clambers into his great grandfather’s portrait and sees his home as it used to be, generations before.

Who knows

when the first person looked at a picture and imagined being inside it? We

cannot know, but it’s a natural thought and I would guess a very old one. In

his remarkable analysis of prehistoric cave art, ‘The Mind in the Cave’ (2002),

David Lewis-Williams suggests that ‘one

of the uses of [Paleolithic] caves was for some sort of vision questing’ and

that ‘the images people made there related to that chthonic [subterranean] realm.’

Adding that sensory deprivation in such remote, dark and silent chambers may

have induced altered states of mind, he continues:

In their various stages of altered states, questers sought,

by sight and touch, in the folds and cracks of the rock face, visions of

powerful animals. It is as if the rock were a living membrane between those who

ventured in and one of the lowest levels of the tiered cosmos; behind the membrane

lay a realm inhabited by spirit animals and spirits themselves, and the

passages and chambers of the cave penetrated deep into that realm.

The Cave in

the Mind, David Lewis-Williams, p214

Locating lines, shapes and holes in cave walls reminiscent of animals or bits of animals, these early people painted in eyes, nostrils, identity – making them emerge out of the rock.

Here is a ‘mask’ from the deepest passage of Altamira Cave in Spain. It could be a horse, but it remains ambiguous. Lewis-Williams quotes an American archeologist, Thor Conway, who visited a Californian rock art site called Saliman Cave:

Red and black paintings surround two small holes bored into

the side of the walls by natural forces. As you stare at these entrance ways to

another realm, suddenly – and without voluntary control – the pictographs break

the artificial visual reality that we assume.... Suddenly, the paintings

encompassing the recessed pockets began to pulse, beckoning us inward.

Painted Dreams, Native Americal Rock Art,

T.Conway, p109-10

Lewis-Williams comments that certain South African rock paintings by the San, that 'seem to thread in and out of the the walls of rock shelters' may 'similarly came to life and drew shamans through the ‘veil’ into the spirit realm.’ So is it possible that the notion of paintings as portals may go back all the way to the Paleolithic? That’s quite a thought.

The Snake-Charmer by Henri Rousseau, 1907, Musee D'Orsay, wikipedia

The Voyage of The Dawn Treader: illustration by Pauline Baynes

Marianne Dreams: illustration by Marjorie Ann Watts

Katie's Picture Show: illustration by James Mayhew

The Cornfield by John Constable, 1826, National Gallery

Photo from Altamira Cave: David Lewis-Williams, 'The Mind in the Cave'