|

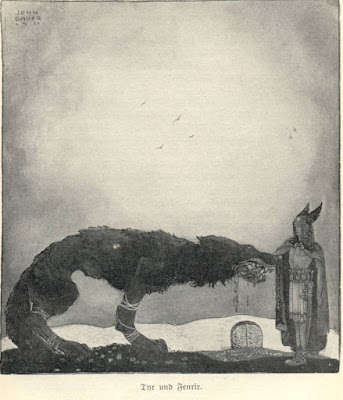

| ‘The Binding of Fenris’, ill. Dorothy Hardy |

This

is the full text of the Katharine Briggs Memorial Lecture as I gave it to the Folklore

Society on 8th November 2022. If you would prefer to watch, there’s a link at the bottom to the Youtube recording

of the event made by the Folklore Society. To everyone of whom, my thanks.

I am honoured to be speaking to you today, and not a little daunted when I think of the many eminent scholars who’ve given the Katharine Briggs Lecture before me. I am not an academic. However, I have loved folk- and fairy tales since I was a child and I’ve been writing and telling stories for most of my life, so when I received the Folklore Society’s invitation I knew I wanted to talk about the power stories have, for both good and ill, and about the different kinds of belief with which we approach them. So this evening I shall be talking about the gruesome tales children tell each other at sleepovers, about legends and fairy tales, and about those stories handed down in families, communities and nations which confer a sense of common identity and pride – sometimes at the cost of excluding others.

The Prose Edda tells of the wolf Fenrir, one of Loki’s three monstrous children by a giantess. Knowing that Fenrir was fated to harm them, the gods bound him with an iron fetter, pretending it was a game to try his strength. Fenrir snapped it easily, and he broke the next one they made, too, though it was twice as thick. Then the gods sent down to the home of the dark elves, where the dwarfs forged a fetter from mysterious, invisible, impalpable things: the footfall of a cat, a woman’s beard, the roots of a mountain, the breath of a fish, the spittle of a bird. It looked harmless – as smooth and soft as a silken ribbon, but Fenrir suspected a trick. He would not allow himself to be bound with it until Tyr agreed to place his right hand between the wolf’s jaws as a pledge of good faith. Tyr lost his hand, but for all his struggles Fenrir could not break the silken fetter.

Once upon a time, all stories existed only in the imaginations of those who told and heard them. Now stories are written down and printed in books, but a book is not a story. It’s just a container. If there are any stories in the Minoan script Linear A, they do not exist for us and never will, unless someone manages to decode and release them. Stories are words made of air, syllables on the lips, communications between minds: as invisible and impalpable as the things the dwarfs wrought into Fenrir’s fetter – and as strong.

In his essay ‘On Fairy-Stories’ JRR Tolkien says, ‘Spell means both a story told, and a formula of power over living men.’[1] It is we who give stories this power, we enspell ourselves: when we read or hear a story it becomes in some sense ‘real’ for us: we believe it. ‘In some sense’: belief is a sliding scale.

Coleridge in his Biographia Literaria defends the ‘supernatural, or at least romantic’ character of his poetry by explaining his intention to ‘transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of the imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.’ As Coleridge tells it then, ‘suspension of disbelief’ is the conscious action he calls ‘poetic faith’: a surrender to story on the understanding that although it is fiction, within its parameters it can tell important truths. And this surrender is or should be temporary: that’s what he means by ‘suspension of disbelief for the moment.’ Tolkien says something not dissimilar: he claims that the story-maker creates a Secondary World ‘which your mind can enter. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside.’[2]

Yet why should Coleridge feel the need to articulate a formula for enjoying stories, an activity which most people find easy as breathing? I suggest, because he was a child of the Enlightenment who assumes in his educated audience a rational scepticism towards the supernatural which he, and they, must work to overcome.

|

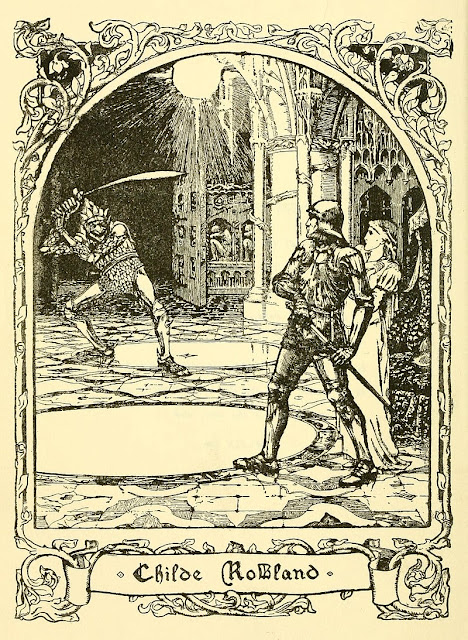

| Childe Rowland: ill. John Batten |

Coleridge’s contemporary, the antiquary Robert Jamieson, recounted how as a child, he was told the story-ballad of Childe Rowland by ‘a country tailor’ whom he patronisingly describes as ‘an ignorant and dull, good sort of man, who seemed never to have questioned the truth of what he related.’[3] His assumption of the man’s credulity may have been correct but seems unlikely given the fantastic nature of the tale, and I wonder whether Jamieson could differentiate, aged seven, between a tale told with conviction and one told as truth? But given the inference that belief in fantastic stories was for the lower classes, Coleridge’s ‘suspension of disbelief’ allowed sophisticated readers to engage with a poem like The Rime of the Ancient Mariner without feeling foolish. Cue: the Romantic period.

We may disbelieve in a story if it’s badly told (when it’s the storyteller’s fault) or if we are out of sympathy with the subject (when it is our fault), but to fully experience a story we must come to it as little children are said to come to the Kingdom of Heaven – with openness and trust. With belief in fact, belief that comes with risks unless at the end of the story the reader or listener can disengage from it. This is important.

Both Coleridge and Tolkien seem to suppose that when the story ends you are out of it – back in the real world, snap! – that disengagment from belief is automatic. But I am not so sure. Aged nine or ten, my daughters would sometimes go to sleepovers – particularly at Halloween – where the children would swap stories, scary ones, including some really gruesome urban legends. There was one of a murderous doll which climbs the stairs, calling to the cowering child above, ‘So-and-So, I’m on the first step! So-and-So, I’m on the second step!’ (A version of this was published in 1897 with an anxious note by the collector[4]: ‘It is hoped that this tale will not be reprinted in any book intended for children.’) There was the babysitter who answers the phone to a strange voice chanting, ‘Go check on the children! Go check on the children!’ and when she does there’s blood on the children’s pillows and a murderer hiding in their parents’ bed. And there was one with a serial-killer-clown whose grotesque, painted face peeps through the window at night. Maybe these tales were enjoyable in the context of a cosy bedroom full of other kids, with treats and drinks and fairy-lights – but for the next few nights at home there would be the patter of feet on the stairs and a distressed little voice crying, ‘I can’t get to sleep! I can’t help thinking about that story...’

It is no earthly use saying to a terrified child, ‘Don’t be silly, it was only a story.’ That is no comfort at all. Only a story? Children know what adults often fail to realise: a story is one of the strongest things there is. Indeed it’s not only children who sometimes find belief lingering uncomfortably beyond the end of a tale. Who hasn’t felt that prickle between the shoulderblades on finishing a ghost story rather too late at night?

The only thing powerful enough to counteract a story – is another story. I would sit down with my children and retell these tales, inventing banal explanations for the scary bits, to neutralise them. The doll on the stairs didn’t mean any harm. It was proud of having learned to climb them, and only wanted the little girl in the bedroom to know how high it could get! The caller who says ‘Go check on the children’ is their dad calling from the restaurant because he knows his kids are liable to misbehave. So the kids are listening from the top of the stairs, and when the babysitter comes up, they’ve squirted ketchup on the pillows to scare her and piled into their parents’ bed to hide. And the clown who peers through the windows? He’s not a murderer! He’s scared and lost and lonely. He fell out of the moving caravan and knocked himself out, and he’s just trying to catch up with his friends in the circus.

I promise you, this works when nothing else does. Once I had retold any of these stories it lost its power: the children were never frightened by it again. But you have to do it with complete confidence, with certainty. Tolkien is right: the storyteller casts a spell and stories are powerful magic. In remaking the scary stories I remade that world into a safe, ordinary one. I used magic to fight magic.

We believe stories differently according to how closely or not they seem to adhere to real life. Urban myths about murderers and clowns frighten children because clowns and murderers really exist, so the horrible things in the story might happen to them. They are not often frightened by giants or dragons. About ghosts, though, the jury is out. Plenty of adults believe in them, at least part of the time, and if a trusted friend tells us they have seen a ghost, what do we do? What we often do is withhold disbelief – which is not the same thing as Coleridge’s ‘suspension’. We suspend disbelief in stories we know to be fiction. Withholding disbelief is what we do when we’re not sure, when we don’t know what to think. The boundary between reality and unreality is porous, or people wouldn’t send Christmas cards to characters in soap operas (though perhaps from a desire to share in that world, rather than from naïvety). We live, far more than we realise, in our imaginations.

|

| Frontispiece: The Fairy Mythology: ill. George Cruickshank |

A

tale recorded in Thomas Keightley’s The

Fairy Mythology of 1828 illustrates our reluctance to disbelieve a tale

told by somebody we know, and I suspect it’s also an early example of my own

strategy for soothing frightened children. Keightley calls it Addlers and Menters[5]. The tale is narrated by two

different voices.

An old lady in Yorkshire related as follows:– My eldest daughter Betsey was about four years old; I remember it was on a fine summer’s afternoon, or rather evening, I was seated in this chair which I now occupy. The child had been in the garden, she came into that entry or passage from the kitchen (on the right side of the entry was the old parlour-door, on the left the door of the common sitting-room; the mother of the child was in a line with both doors); the child, instead of turning towards the sitting room made a pause at the parlour-door, which was open. She stood several minutes quite still; at last I saw her draw her hand quickly towards her body; she set up a loud shriek and ran, or rather flew, to me crying out “Oh! Mammy, green man will hab me! green man will hab me!”

It was a long time before I could pacify her; I then asked her why she was so frightened. “O Mammy,” said she, “all t’parlour is full of addlers and menters.” Elves and fairies I suppose she meant. She said they were dancing, and a little man in a green coat with a gold-laced cocked hat on his head, offered to take her hand as if he would have her as his partner in the dance.

The mother, upon hearing this, went and looked into the old parlour, but the fairy vision had melted into thin air.

“Such,” adds the narrator, “is the account I heard of this vision of fairies. The person is still alive who witnessed or supposed she saw it, and though a well-informed person, still positively asserts the relation to be strictly true.” * [Here Thomas Keightley adds an asterisk which leads to a cautious, sceptical footnote]: *And true no doubt it is: ie: the impression made on her imagination was as strong as if the objects had been actually before her.

Clearly

Keightley didn’t believe the child really saw a fairy. But it wasn’t his story.

He found it in a letter printed in The

Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences of 16th

April1825. The anonymous correspondent had been reading Thomas Crofton Croker’s

recently published Fairy Legends and

Traditions of the South of Ireland, and wrote:

Mr Croker... says that fairies have not been seen for many years in the North of England. I can inform him, if not in the memory of man, they have been seen in the memory of woman, in a village in the East Riding of Yorkshire. A respectable female, who is nearly [ie: closely] related to the writer of this, and who is now alive, beheld, when she was a little girl, a troop of fairies “deftly footing a roundel daunce” in her mother’s large old wainscoted parlour… I have frequently heard it related by her venerable mother, and subsequently by herself.[6]

This was a family story, told first-hand. The little girl’s pause by the parlour door, the sharply observed gesture of ‘drawing her hand quickly towards her body’ and her terrified shriek, suggest a genuine experience, if only a frightening waking dream. We can be pretty sure that whatever little Betsey thought she saw, the words given to her are exactly what she said. ‘Addlers and menters’? Even her mother wasn’t sure what it meant. ‘Oh mammy, green man will hab me, green man will hab me!’ That sounds true too. But the civilized little man in green coat and gold-laced hat who invites the child to dance is hardly convincing as the source of such childish terror.

|

| Portrait of a Gentleman’, Joseph Wright c 1760 |

Gold laced cocked hats were high fashion in the first quarter of the eighteenth century, came briefly back in the 1770s, and vanished at the start of the French revolution in 1789. We do not know Betsey’s age in 1825, the date of the letter; she may have been middle-aged or more, but as a four year-old in an East Riding village would she even have seen such a hat – still less been able to describe it? You can hear the uncertainty in the letter-writer’s voice: he knows this lady, she’s positive about what she saw, and her mother witnessed her reaction to the event. Something happened. He can’t quite believe it – but he withholds his disbelief.

Whatever it was that scared Betsey, I can’t help thinking her mother invented the courtly little man to make it less terrifying, as I did for my children. ‘A green man, darling? Oh, a lovely little fairy man in a gold-laced hat! He didn’t mean to frighten you. He only wanted to ask you to dance!’ And such is the power of motherly suggestion, the child soon agrees that’s what she saw. This ‘explanation’ transforms a moment of fright into a more comfortable yet fascinating story, and ‘the time Betsey saw fairies dancing’ becomes a bit of family history that evokes pride and even wonder.

|

| Family photo: author's possession |

This is my grandmother, Helena Beatrice

Langrish, born into a British army family in India, in 1886. She was a great

raconteur, and many of her stories involved men whose attentions she had to evade

or fight off; these invariably emphasised her attractiveness and courage. She

told one about four soldiers who surrounded her as she walked home from playing

tennis: ‘They never said a word – they just looked at me. All I had with me was

my tennis racket, Katherine!’ When an appeal to their honour failed – ‘You’re

British soldiers! You wouldn’t hurt a woman!’ – she turned to threats: ‘I shall

tell the colonel of you!’ – ‘They fled, Katherine! They fled!’ Left at that,

this would be little more than an anecdote, but the tale continues to a

punchline. The colonel, to whom she had indeed complained, paraded the

battalion and lectured them on proper behaviour to women, after which he

privately told her:

“You’re a very lucky woman, Mrs Langrish. Those men who accosted you”.... drumroll ... “were all gaolbirds!” And she would repeat, face vivid with the drama of it all, “All gaolbirds, Katherine!”

Like the ‘explanatory’ ending of Betsey’s tale, this coda in which my grandmother discovers the narrowness of her escape transforms a genuine yet brief scare into a memorable story. And do I believe it? There’s nothing obvious to disbelieve, so yes, mostly... but like Betsey’s, stories grow in the telling.

Belief is not an ‘on or off’ binary

affair, but a whole spectrum. Stith Thompson has placed ‘the wonder story like The Dragon Slayer or Faithful John at one extreme of folk

tradition and actual beliefs in

various supernatural manifestations at the other’. And he adds: ‘sharp lines

are hard to draw [...] All depends upon the attitude of hearer and teller.’[7]

Like family stories and ‘true’ ghost stories, local legends are located in the real world – with temporal and spatial reference points. They attract varying degrees of belief. The Cow and Calf Rocks on Ilkley Moor are said to have been dropped there by a giant called Rumbald, but I doubt anyone ever believed it, any more than they’d believe the moon is made of green cheese. People aren’t fools. The many comic folktales in which the devil comes off worst, as when St Dunstan pinches his nose with red-hot tongs, were surely always entertainment: but a scare-story of demonic apparitions in your own neighbourhood might be taken differently.

|

Detail: ‘Die Wilde Jagd' (anon) in 'Der Orchideengarten' 1920 |

The Peterborough

manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells of the appearance on February 6th

1127 of what we generally call the Wild Hunt:

Many people saw and heard many hunters hunting. The hunters were black and big and loathsome, and their hounds all black and wide-eyed and loathsome, and they rode on black horses and black goats. This was seen in the very deer-park in the town of Peterborough, and in all the woods ... between this town and Stamford, and the monks heard the horns blow that they were blowing at night.[8]

The existence of

a terrifying devil was church orthodoxy, and people may well have believed this.

All the same, the appearance of the hellish hunters coincided with the arrival

of a new, unpopular abbot who’d been foisted upon the monastery by Henry I. Supernatural

or not, the event was used as propaganda to discredit the abbot. It’s always a

good idea to ask who is telling the story, and why.

There are strange tales without an obvious purpose. That of the Green Children, said to have occurred in the reign of King Stephen, was recorded independently by William of Newburgh and Ralph of Coggeshall and still arouses curiosity. Two green children were found near Woolpit in Suffolk. They spoke an unknown language, ate nothing but beans, and later claimed to have come from an underground land suffused with a pale, unearthly light. Katharine Briggs remarked that the tale had ‘a curiously convincing and detailed air’[9], and modern commentators have found explanations ranging from ‘folk tale motif’, to ‘green skin caused by chlorosis or arsenical poisoning’ to ‘extraterrestrials’. The story is intriguing; people want to believe it – and exert themselves to find ways of doing so.

Devils are hard to believe in these days, but there are still people who claim to have seen fairies[10], while ghosts are evergreen. An article from July 2019 on the website ‘Kent Live’ reports a haunting on the A229 Blue Bell Hill road ‘with many motorists claiming to have seen a young bride waiting by the roadside. It is believed this ghost is that of 22-year-old bride Suzanne Browne, who was killed with two friends in a road traffic accident on the eve of her wedding on November 19, 1965.’ The details sound convincing. But in October 2020 the website ‘Wales Online’ ran a feature about the same stretch of road which repeats the story, but it’s now ‘Judith Langham, a young bride-to-be killed in a car collision on the day of her wedding’ who haunts the road. Those apparently specific details aren’t as anchored in fact as they seem.

|

| Lord Raglan (wikipedia) |

This

rather grim-looking gentleman is Fitzroy Richard Somerset, 4th Lord Raglan, president

of the Folklore Society from 1945-47. In his 1930s book The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama, he provides a

delightful account of the stages by which a legend may grow from little acorn

to great oak.

Stage 1: This house dates from Elizabethan times, and since it lies close to the road which the Virgin Queen must have taken when travelling from X to Y, it may well have been visited by her.

Stage 2: This house is said to have been visited by Queen Elizabeth on her way from X to Y.

Stage 3: The state bedroom is over the entrance. It is this room which Queen Elizabeth probably occupied when she broke her journey here on her way from X to Y.

Stage 4: According to local tradition, the truth of which there is no reason to doubt, the bed in the room over the entrance is that in which Queen Elizabeth slept when she stayed here on her way from X to Y. [11]

This is shrewd and funny. But such a story is going to be hard to kill in any individual case, because the Queen undoubtedly did spend the night in a great many different English country houses, and absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. The owner of the house, who takes pride in the story, is not going to listen to Lord Raglan casting cold water. Again it’s about wanting to believe. Pride trumps history.

Raglan

was a hard-liner about folk tales. He didn’t think they preserved any

historical information at all, which isn’t surprising when you read his

definition of history: The recital in

chronological sequence of events which are known to have occurred. Insisting

that history depends entirely on written chronology, he claimed that since what

he termed ‘the savage’ cannot write, ‘the savage can have no interest in

history.’

When we read of the Irish blacksmith who said that his smithy was much older than the local dolmen … we are apt to suppose the speaker exceptionally stupid or ignorant, but [his] attitude towards the past is similar to that of the Australian black [sic] who began a story with: ‘Long long ago, when my mother was a baby, the sun shone all day and all night’, and is the inevitable result of illiteracy. [12]

Raglan’s contemptuous

tone does him no credit; and he makes a category error: the Indigenous

Australian storyteller is using an opening formula found all over the world,

that places a traditional narrative far away and long ago: ‘Once upon a time’

and the tale, published in Folklore

in September 1934, is an origin myth, a just-so story to explain solar

eclipses. It tells of a golden age when everyone was happy and ‘the sun shone

all day and all night’- as it would, in the golden age! Alas, some people became

lazy and quarrelsome, upon which the sun and moon descended and split the earth

in two, leaving the happy people on one side and the discontented ones – us! –

on the other. When the happy people want to see what we are doing, they tip the

sun on its side and crowd to look down on us, covering the sun and making it

dark. I see no essential difference between this, and Hesiod’s account of the

golden, silver and bronze ages of mankind, but I doubt Raglan would have sneered

at Hesiod.

Compare that opening sentence with one from a Romanian fairy tale: ‘Once upon a time, far far away, as far as the spot where the Devil weaned his children...’[13]

Or one heard around 1860 by Henry Mayhew from a seventeen year-old lad in a London workhouse: ‘Once upon a time, and very good time it was, though it was neither in your time, nor my time, nor nobody else’s time...’[14]

Or even this: ‘A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…’

Such openings are not naïve. The storyteller knows very well there never was a time when the sun shone all day and night. The concept is deliberately surreal. Origin myths are not to be taken literally: they are fables to provoke thought and wonder. As for fairy tales, they openly flaunt their unbelievability. Shelves full of books have been written to prove or disprove the historicity of King Arthur or Robin Hood, but no one has ever asked if the story of Cinderella really happened, or pointed out the ruins of the Sleeping Beauty’s castle.

Like The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, fairy tales are full of ‘persons and characters supernatural, or at least romantic’ and we approach them with, let’s use Coleridge’s beautiful term, ‘poetic faith’. The wondrous events of fairy tales will not fool anyone, but this doesn’t mean they are trivial. The Ancient Mariner sins, suffers, repents, is forgiven – yet is left with the obsessive need to tell his tale over and over. Post-traumatic stress is nothing new.

Neither do fairy tales shrink from the dark side of life. Abuse, fraticide and child-murder are not uncommon; fairy tale families are frequently disfunctional. Mothers die, stepmothers are cruel, fathers are weak, selfish, even incestous, family friction often forces the protagonist out into the world. These things are not fantastic, but fairy tales mediate them to us within the bounds of an explicitly fantastic genre. The most unrealistic thing about the fairy tale is not the magic. It is the happy ending.

|

| Dorothea Viehman: portrait by Ludwig Grimm (wikipedia) |

The people who made and told the tales were poor, often illiterate, and lived hard lives. I’ve already mentioned Robert Jamieson’s story-telling tailor. Here is Dorothea Viehmann, a tailor’s wife who contributed many stories to the Grimms’ first collection. William Larminie, who collected stories in Ireland in the 1880s, describes his contributors with considerable respect (in welcome contrast to Lord Raglan). Of Pat Minahan of Glencolumkill, for example, he says:

[F]rom him I obtained more stories than from any

other man. He said he was eighty years of age; but he was in full possession of

all his faculties. His style, with its short, abrupt sentences, is always

remarkable and at its best I think excellent.[15]

Another was Pat McGrale, Jack-of-all-trades, boatman and fisherman, who ‘can read Irish but had very little literature on which to practise his accomplishment. He knows some long poems by heart.’ J F Campbell describes a seventy-nine year old man from South Uist: ‘He seemed to know versions of nearly everything I had got, and told me plainly that my versions were good for nothing. “Huch! Thou hast not got them right at all.”’ [16]

These were the folk who were telling, making and remaking the fairy tales we know. They sound a sharp, intelligent bunch, sophisticated storytellers who could and did link tales together into long chains that might run on for a whole night or series of nights. The Highland gamekeeper Hector Urquhart told J F Campbell: ‘It was a common saying, “The first tale by the goodman, and tales till daylight by the guest.”’[17] Here was live entertainment, exciting and colourful, and it bound communities together until, as Urquhart went on to say, ‘The minister came to the village in 1830, and the schoolmaster soon followed, who put a stop in our village to such gathering; and in their place we were supplied with heavier tasks than listening to the old shoemaker’s fairy tales.’ This suppression occurred because for two centuries the Presbyterian church had associated the fairies with the devil and witchcraft. In the clash of beliefs, as usual, the authorities won.

|

| Hansel and Gretel: Anton Pieck |

Told and disseminated by the common people, fairy tales favour the underdog. Hansel and Gretel is all about food and hunger: parents who choose between starving to death or abandoning their children. The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids features a single mum who must go out to work, leaving her children in danger – and yes, she’s a goat. Of the 145 Grimms tales that are actually about human beings (rather than animals or objects) – a whopping 84% follow the fortunes of poor people: peasants, millers, tailors, servants, shoemakers, tradesmen and furloughed soldiers. They nearly always end rich or married to royalty, or both: but that’s not how they start.

Fairy tales are aspirational and disruptive. The peasant lad marries the princess, the wicked king is thrown down. Young women possess the wit or magical skills to trick their giant or troll father-figures and save their lovers. The girl who sits in the ashes gets to wear the dress as golden as the sun. Fairy tales offer a world ruled by justice – not mercy. They are experiments in karma, if you like. Here if anywhere, the innocent and good will triumph, kindness and generosity will be rewarded, and the wicked will be punished: they will dance themselves to death in red-hot shoes, or be rolled downhill in barrels full of spikes. In Charles Perrault’s civilised Cendrillon the sisters are forgiven and marry lords, but in the Grimms’ version, which as a child I much preferred, they cut off their own heels and toes, and doves peck their eyes out. We may wince, but fairy tales are brisk about such things, and never graphic.

The

context of GK Chesterton’s remark: ‘Children are innocent and love justice, but

adults, being sinful, naturally prefer mercy’ was that he had been to see

Maeterlinck’s play The Blue Bird with

some children who were upset that the hero and heroine never find out that ‘the

Dog was faithful and the Cat faithless’. The children were right. Justice comes

before mercy, and the real world is and perhaps ever shall be short on both.

Fairy tales offer the assurance that justice is important and does

exist... on some Platonic plane, somewhere.

|

| Changeling: Andrew Paciorek http://www.batcow.co.uk/strangelands/solitary.htm |

Fairy

tales, wonder tales, have undoubtedly contributed to the sum of human happiness.

I doubt if they have ever done any harm. Only the stories that masquerade as

truth can do that. Folktales of changelings and fairy abductions are found all

over Britain and often include violent methods of bringing the ‘true’ child or

wife back, such as burning, drowning or exposure. In 1827 the Dublin Evening

Mail reported a trial at Tralee Assizes[18]:

Tralee Assizes, July 1826. – Child Murder – Ann Roche, an old woman of very advanced age, was indicted for the murder of Michael Leahy, a very young child, by drowning him in the Flesk. [...] The child, though four years old, could neither stand, walk or speak – it was thought to be fairy-struck – and the grandmother ordered the prisoner and one of the witnesses [...], to bathe the child every morning in that pool of the river Flesk [...] and on the last morning the prisoner kept the child longer under the water than usual [...]. Upon cross-examination, the witness said it was not done with intent to kill the child, but to cure it – to put the fairy out of it.

The magistrate directed the jury to find Ann Roche not guilty of murder, on account of her delusional beliefs. In 1885 a young Irish woman called Bridget Cleary was beaten and burned to death by her father and husband, who believed the real Bridget had been taken by the local fairies. And (though she gives no reference) Katherine Briggs, in A Dictionary of Fairies, mentions a child burned to death at the beginning of the 20th century ‘by officious neighbours who put it on a red-hot shovel in the expectation that it would fly up the chimney’.[19]

It’s not hard for people to believe narratives that fit ‘what everybody knows’. If we return to Lord Raglan’s definition of history, ‘the recital in chronological sequence of events which are known to have occurred’ – he thought, and a lot of people still think, history is all facts and dates and dated events, and being able to prove conclusively that certain things happened and where they happened, and when. But another view is that history is what goes on inside our heads – the things we remember, the stories we’ve been taught, shaped and driven by emotions like pride, patriotism, nationalism. Not just history, but our lived reality is made of stories, which may be neither accurate nor complete.

And deliberate efforts have been made by those in power to suppress tales of which they disapprove, as the minister and schoolmaster suppressed the Highland tales, and as I discovered while researching my 2007 children’s novel Troll Blood, set in an imaginary, magical Viking Age. The story took my characters across the Atlantic to Vinland: North America; the Greenlanders Saga tells how Thorvald Eiriksson and his men met, fought, and murdered indigenous people there: people my characters would also have to encounter. Since the book was a fantasy, I wanted to include on the North American scene creatures in some way parallel to the trolls, nisses and nixies my Norse characters knew. A belief in trolls characterises and differentiates a group of people from another group – one which believes in nymphs, for example. Without reference to the folklore and beliefs of the people I’d be writing about, I would be missing an important dimension.

Clearly no one in the 10th century was collecting First Nations folklore, so instead I explored the later-recorded folklore of a range of North-East Woods peoples, especially the Mi’kmaq of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, whose ancestors at least could have encountered Norse voyagers. I spent months in the Bodleian doing this: one particular story was collected in the mid 1920s by the anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons from a Mi’kmaw woman called Isabelle Googoo Morris, about some creatures called the hamaja’lu:

These are very small beings, no larger than two finger joints. There are thousands of them who live along the shore. [...] Once when some men landed on the shore for a short time, before they took to their boat again they saw a model of themselves and their boat made in stones by the hamaja’lu. They work very fast.[20]

|

| Pebble figure on Lindisfarne: author's photo |

This seemed delightful, and the hamaja’lu went into my book. When it was finished I sent it to be checked by Dr. Ruth Holmes Whitehead, an expert in Mi’kmaw studies, who set me right on several points. But I was rather dismayed when she asked me to correct ‘the hamaja’lu’ to ‘the wiklatmuj’ik’, a far more difficult word to read and pronounce. I asked why, and she wrote back, ‘There is no ‘h’ in modern Mi’kmaq, and this word is obsolete. The word used today is the one I have given you.’ This surprised me: how could a word used freely in the 1920s – there were several stories about the hamaja’lu – have died out? Back came the reply: ‘You would not find it so surprising if you were aware that, during the course of the 20th century, generations of Mi’kmaq children were taken from their parents, put into homes, taught European ways, and punished – beaten, shut in cupboards, thrown down stairs – for speaking their own language.’ I took her advice.

Though stories about the hamaja’lu were written down in the 1920s, they’re not told any more. The wiklatmuj’ik are not the same; much bigger, for one thing. Such tales are more than curiosities. The now-forgotten hamaja’lu may never have had objective reality, but they were once part of a belief system, part of Mi’kmaq identity. And that was what the Canadian Government of the time was trying to eradicate.

Despite

such losses, the Mi’kmaw language survived, and so has the culture and people,

but in the introduction to the Indigenous Australian origin myth I mentioned

earlier, I found this unemotional but terrible statement:

The myths and folktales presented in this paper were collected from the Wheelman [Wiilman] and neighbouring tribes of South-Western Australia which lived in the region inland from Bremer Bay. These tribes are now extinct so that the material included herewith probably represents all the tales which will ever be known from this part of Australia.[21]

The myths and tales were collected in the 1880s. The paper was published in 1934. Just fifty years. I checked and in fact the Wiilman people still exist, but their language is extinct: it will have been lost through the same tactic of taking children away from their parents. The sorry pattern of Western culture imposing itself on the cultures of indigenous peoples been repeated many times.

So what about our own national identity, what stories do we tell about ourselves? Probably the most resonant in popular memory are still those of the Battle of Britain, and the little ships at Dunkirk. They may well inspire us, but they are our grand-parents’ stories, not ours. We should be careful of bathing in unearned, reflected glory and clinging too closely to the past.

|

Here is OUR ISLAND STORY, a History of England for Boys and Girls by Henrietta Elizabeth Marshall, published in 1904. It is still in print.

The opening chapter tells how Neptune and Amphitrite had a son called Albion and gave him an island: ‘a beautiful gem in the blue water’. Albion ruled this island until he was killed in a fight with Hercules, and then Brutus arrived from Troy to fight and kill the giants who lived here, and when Neptune retired as a god, because he had loved Albion so much he gave his sceptre to the islands now called Britannia: ‘For we know – Britannia rules the waves.’

Now

that’s pure fairy tale, even if most of it’s based on Geoffrey of Monmouth’s 12th

century History of the Kings of Britain

which itself, as you’ll well know, is almost entirely fiction. The author ends

the chapter with perhaps the blandest account of colonialism I’ve ever read:

In this book you will find the story of the people of Britain. The story tells how they grew to be a great people, till the little green island set in the lonely sea was no longer large enough to contain them all. Then they sailed away over the blue waves to far-distant countries. Now the people of the little island possess lands all over the world.[22]

No mention, you’ll notice, of the peoples our ancestors dispossessed.

David

Cameron has gone on the record three times, describing how Our Island Story’s version

of British history shaped his mind. He referenced it in a speech delivered in

2014 just before the Scottish Referendum, to deliver a message of national

unity:

I have an old copy of Our Island Story, my favourite book as a child, and I want to give it to my three children, and I want to be able to teach my youngest, when she’s old enough to understand, that she is part of this great, world-beating story. And I passionately hope that my children will be able to teach their children the same.

Our Island Story is almost entirely folktales. There’s Merlin, there’s King Arthur – ‘only fifteen when he was made king, but the bravest, wisest and best king that had ever ruled in Britain.’ There’s Robin Hood and his Merry Men...

|

| Elizabeth and Raleigh: Herbert Moore 1908 |

... and Sir

Walter Raleigh throwing down his cloak for Queen Elizabeth – for which there is

no contemporary evidence. Marshall even presents Raleigh as a benefactor of the

Irish:

Two of the things Raleigh brought home [from the Americas] were tobacco and potatoes. [Queen] Elizabeth had given him estates in Ireland, and there he planted the potatoes and showed the people how to grow them. Even to this day the poor people in Ireland grow potatoes and live on them very largely.[23]

Raleigh received his Irish lands as a reward for helping to put down the Desmond Rebellions, when he took part in at least one massacre, so this account of him as a sort of kindly agriculturalist is alternative fact – if you remember that phrase coined by Kellyanne Conway – of a high order.

Our Island Story is not honest. It is propaganda designed to invest a child with a particular identity: the son or daughter of a heroic, benign and glorious British race. Blurbs on Amazon hail it as a ‘compelling narration’ that lauds ‘the valiant spirit of Richard Lionheart who led the Third Crusade’. The book of course includes no account of that king’s decision to massacre almost 3000 Muslim prisoners – men, women and children – at the Siege of Acre. No wonder then, that one five-star review reads: ‘Parents, grandparents and teachers, this timeless classic will help the children in your life learn their country’s history and be proud and grateful for it!’

These stories, these folktales, are woven into the British historical narrative. They still influence real people, real politicians, real events. We live more than ever before in a world of conspiracy theories, fake news, competing versions of events – all stories, and it’s more important than ever to be able to distinguish between them. No history book can tell everything, but balance is required. It may not be pleasant to learn from David Olusoga[24] that even after the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade in 1807, much of Britain’s wealth continued to depend on the sugar plantations of the West Indies where slavery did not end until 1838 after a series of bloody uprisings – but it’s important. When we don’t hear these stories, and the statue of a slave-owner gets toppled into a harbour in Bristol, then people object and up goes the cry of ‘rewriting history’. But every nation has its dark side, and nations, like people, should admit their faults.

Stories are wonderful. They entertain, instruct, frighten, comfort, amaze: they offer hope, wonder, solace. They bind us together in families, communities, nations. They have the power to command belief. We just need to be careful what sort.

Author's copy: frontispiece and title page

Friedrich

de la Motte Fouqué’s 1814 romance Sintram

and His Companions is a remarkable fairy tale set in a medieval

Norway-that-never-was. It’s an eerie, powerful fable about temptation and the

struggle for righteousness: Sintram’s terrible companions are a spectral Death

and a dwarfish Sin. The preface to my1883 edition includes a wonderful

quotation from ‘Mr Linklater, curate of St Peter’s, London Docks’, who read the

tale aloud to ‘the rough lads’ of his Bible class:

It was my compact with them that if they were good and attentive at lessons I would afterwards tell them a story, or show them pictures. ... But I was most astonished at what I considered a daring experiment, the reading to them Sintram. It made the most wonderful impression on them. They wrought it into their own lives. They called the different localities of the parish by the names in the book. They literally hungered for the next week’s portion. I believe that nothing I have ever read or said to them has affected them so lastingly as this.[25]

I find that incredibly moving. In creating and believing in stories, we create and believe in ourselves. Among the many definitions of what it means to be human, the capacity to make up stories may endure as a distinguishing feature – although who knows what the whales are singing? Let me quote from an essay I wrote several years ago, for I don’t think I can put it any better:

We pass through the world surrounded by mysteries – things which are not, which have no physical existence. There is the past, which we remember but can no longer touch: a magician’s backward-facing glass in which the dead are still alive and the old are still young and can be seen going about their affairs, ignorant of our gaze, in tiny bright pictures with the sound turned down low. Then there is the distance – that blue trembling elsewhere on the rim of the horizon beyond which, perhaps, everything is different, new and wonderful. And there’s the invisible future into which we constantly travel with our baggage of hopes and promises, longings and fears.

The before-and-after of life is a great darkness, and we build a bonfire to light and warm and comfort ourselves – the bonfire of culture: myths, stories, songs, music, poetry, religion, art and science. All these things spring from the human struggle to apprehend the world and our place in it: and the untouchable existence of such things as the past, the future, the horizon, has given us confidence to imagine and discover and invent and delight in other things which can neither be seen nor approached nor touched. Right and wrong. Gods, ghosts and mathematics. And of course...

|

| Tyr and Fenrir: John Bauer |

I began this evening with the wolf Fenrir, for whom the dwarfs wrought that cord of other, equally impossible things. He was suspicious of it from the start, saying: ‘This ribbon looks to me as if I would gain no renown from breaking it – it is so slight a cord; but if it has been made by guile and cunning, slender though it is, it is not going to come on my legs.’[27] But he was persuaded, and once entangled he was unable to get free. All the same, he will eventually break loose on the day of Ragnarok. Perhaps it was his belief in the cord that imprisoned him. Perhaps it was the guile, the cunning, the spell of story that bound him, after all.

The link to the Youtube recording of the event made by the Folklore Society:

[1] Tolkien, JRR, ‘On Fairy-Stories’, The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, George Allen & Unwin, 1983, 128

[2] Tolkien, ‘On Fairy Stories’, The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, George Allen and Unwin, 1983, p132

[3] Jamieson, Robert, Illustrations of Northern Antiquities, 1814, pp 397 et seq

[4] Addy, S.O.,‘The Old Man At the White House’: Four Yorkshire Folktales, Folklore Vol 8, no 4, December 1897

[5] Keightley, Thomas, The Fairy Mythology, 308 et seq

[6] op cit

[7] Thompson, Stith, The Folktale, Dryden Press 1951, p263

[8] Douglas & Greenaway, English Historical Documents, Vol II Eyre Methuen 1981, 204

[9] Briggs, KM, The Fairies in Tradition and Literature, Routledge & Kegan Paul 1967, 7

[10] Documented by Simon Young and Ceri Houlbrook, Magical Folk, Gibson Square 2018

[11] Raglan, Lord, The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama, Thinker’s Library 1948, 30 et seq

[12] Raglan,Lord: The Hero, Thinker’s Library 1948 p3

[13] ‘The Princess Who Would Be A Prince’: The Foundling Prince and Other Tales, Petre Ispirescu, tr. Julia Collier Harris & Rea Ipcar, Houghton Mifflin Co. NY 1917,241

[14] Mayhew, James, London Labour and the London Poor, Griffin, Bohn & Co, 1861, 391

[15] Larminie, William, West Irish Folk Tales, The Camden Library 1893, pxxv

[16] Campbell JF, Popular Tales of the West Highlands, Alexander Gardner 1890, Vol 1, xxii

[17] op cit vi

[18] Dublin Evening Mail, 17 April 1827, quoted by Thomas Crofton Croker, Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland, 2nd edition, preface.

[19] Briggs, Katharine, A Dictionary of Fairies, Penguin 1977, 71

[20] Parsons, Elsie Clews, ‘Micmac Folklore’, Journal of American Folklore, v.38, 1925, 94

[21] Hassall, Ethel,’Myths and Folktales of the Wheelman Tribe of South-Western Australia’, selected & revised by D.S. Davidson, Folklore Vol 45, No 3, Sept 1934

[22] Marshall, HE, Our Island Story, TC & EC Jack, 1905, p4

[23] op.cit, 344

[24] Olusoga, David, Black and British: A Forgotten History, Pan Macmillan 2016, Chapter Six

[25] De La Motte Fouque, Friedrich, Sintram and His Companions, Seeley Jackson & Halliday 1883, vii

[26] Langrish, Katherine, ‘Desiring Dragons’, Seven Miles of Steel Thistles, Greystones Press 2016, 114

[27] Sturluson, Snorri, The Prose Edda, tr. Jean I Young, U. of California Press 1973, p38