So you're looking for an author who writes adventure stories – and I mean

adventures – with brilliant main characters who more often than not just happen to be female? You are looking for

Fiona Dunbar. There is no earthly reason (other than adult-generated prejudice) why boys as well as girls shouldn’t enjoy her books. Her writing fizzes with energy and ideas and fun: she blithely ignores boundaries between genres, and I’m particularly addicted to her ‘Silk Sisters’ trilogy, beginning with ‘

Pink Chameleon’, set a decade or two into the future, a wildly funny yet thought-provoking mixture of science fiction and – believe it or not – fashion. (Just how far can genome research and nano-technology take us? What if you really ARE what you wear?)

Or there’s her Lulu Baker books which combine fairytales, skulduggery and cookery… or ‘Toonhead’, in which ten year old Pablo (so named by fond arty parents who hope for a budding Picasso) discovers he can predict the future through the cartoons he draws – a skill which gets him kidnapped…or her most recent title, ‘

Divine Freaks’, featuring the irrepressible Kitty Slade, whose talent for seeing ghosts (inherited from her mother) soon leads her into no end of trouble involving a dodgy landlord who wants to evict her family, a scalpel-wielding ghost in the school biology lab, a back-street taxidermist, shrunken heads, and a fraudulent antiques business.

One of the things I like most about Fiona’s books is that her heroines – or the occasional hero – don’t exist in a vacuum. Family is important. The Silk Sisters are desperate to find their missing parents, and the bond between responsible elder sister Rory and her strong-willed little sister Elsie is both funny and touching. In ‘Divine Freaks’, Kitty can rely on her brother and sister for backup, while her Greek grandmother Maro is a reassuring if eccentric presence. This helps steady the reader’s nerves through some of the more exciting passages… as here, when Kitty and her brother and sister secretly enter the taxidermist’s house:

Those knives for slicing open a man’s skull, those needles for sewing up the lips. Just what kind of skins had we seen? And now I thought about the large pots in the kitchen, large enough to contain a whole head…

I steadied myself on the stack of tea chests. “What is Eaton involved with?”

“Does this mean he’s killing people?” asked Flossie…

Sam’s white face was now glistening with sweat. “Wait… not so fast! There has to be some rational explanation for all this.”

There was a click. Followed by a humming sound. We all jumped. Then I realised it was coming from a small fridge in the corner that none of us had noticed before.

We all stared at it. “OK,” I said. “Who’s brave enough to look in there?”

Oh, and before I forget, the ghosts are real ghosts, the magic is real magic. Fantasy meets adventure meets horror meets science fiction. What’s not to like? If you have a ten-to-fourteen year old in your life, get them one of these books immediately! Meanwhile, here is Fiona to talk about one of the old favourites -

CINDERELLA

Hands up who thinks Cinderella is a rather nauseating goody-two-shoes. Just in case there’s any uncertainty, I’m talking about the Cinderella who not only puts up with systematic abuse from her stepfamily without ever standing up for herself, but endures it all with a sweet smile. The one who never once talks to her father about this abuse, and who actually helps her sisters get themselves all tarted up in their finery, while she is dressed in rags. That Cinderella. Oh, you too? Uh-huh.

It’s all Charles Perrault’s fault. Well, not entirely. But only in his version does Cinderella not even ask to go to the ball. Only in his version – and any others based on it – does Cinderella match her two stepsisters up with members of the Prince’s court. A triple wedding takes place, and the sisters and their consolation prize husbands get to have their own quarters at the royal palace.

Now, I’m all for forgiveness, and I can’t say I prefer the comeuppance the sisters get in Aschenputtel, the Grimm brothers’ version – the pecking out of their eyes. But even so, that Perrault ending always bothered me as a child. So the mean, selfish people get to have a happy-ever-after as well, do they? So being nice and good: we needn’t bother with that, then? Waste of time, is it? Of course I’m being facetious, but let’s face it, children are naturally selfish creatures, and altruism is learned. And frankly, if we imagine Cinderella, the Sequel, it’s hard to picture those two suddenly being transformed into gracious human beings. A more likely scenario would contain enough tragic horrors to fill a tabloid newspaper for years: infidelity (their husbands were picked for them! They never actually fancied them), alcoholism (drowning their sorrows, being confronted daily with the awful reality that they will always be the supporting cast, never the stars), vindictive behaviour (unending efforts to drag Cinderella down to their level), assorted other addictions (shopping, gambling, drugs, dieting, cosmetic surgery…)

Ah yes, the cosmetic surgery. That’s another thing that features in Grimm, but not in Perrault. That cutting-off of bits of the feet, in an effort to squish them into that tiny slipper. It is a wonderfully gruesome image, with the blood oozing out (again, it is only in Perrault that the slipper is made of that transparent and incidentally impossibly brittle material, glass). Although Perrault’s tale pre-dates Grimm by over a hundred years, both were drawing on a traditional tale thousands of years old, and I suspect that the prevalent European versions would have been along the lines described by the Grimms.

Eastern versions are less brutal than that of the Grimm brothers. Interestingly, the Chinese version, Ye Xian (AD 850) does not contain any kind of foot mutilation – interesting, of course, because you would think it might, given the appalling Chinese tradition of foot binding. Although this practice seems not to have been introduced until about a hundred years later (during the Southern Tang dynasty, AD 935-975), the idea that tiny feet were considered desirable in a woman was clearly already prevalent. Yet there is no cutting-off of toes here.

This brings me to the second element that bothered me as a child: how the hell Cinderella could be the only one in the entire kingdom with a foot small enough to fit into it.

I mean, come on! Most western females are somewhere between a size 4 and a 7. Some take a size 3; there was a time long ago, when I could just fit into a size 2 ½, but I’m sure I wasn’t the only one. What size was she, for heaven’s sake?

The Chinese version has a way round this plot issue which makes a lot of sense to me: the slipper is magical. It knows who it belongs to, and can change its size every time anyone other than Ye Xian tries it on, so that it is always just too small. And it makes sense that the slipper is magical, because it was supplied by the magical fish that fulfils the role played by the Fairy Godmother in the Perrault version. Sometimes the introduction of magic can seem like a cop-out: not in this case. I think there is a greater internal logic to it.

The reason I chose Cinderella for my fairytale reflection is that my Lulu Baker trilogy, about a girl with a magic recipe book, has been described as a kind of modern Cinderella story. There are some very obvious reasons for this: Lulu is the only child of a widower, and her nemesis is the new love of his life, Varaminta le Bone – whom he is all set to marry. Varaminta is a glamorous forty-something ex-model with a ghastly son called Torquil. Both Varaminta and Torquil are charm itself around Lulu’s Dad, but vicious towards Lulu whenever he’s not around. Which reminds me: I haven’t even had a bitch about Cinderella’s dad yet! Must put that right.

What about the dad, eh?

That spineless wimp who just lets those domineering females rule the roost, either unaware of how they’re treating Cinderella, or worse, noticing it but failing to do anything about it. What a waste of space! Admittedly, the dad in my Lulu Baker books is completely blind to Varaminta’s faults, but I do explain his lack of involvement by making him extremely busy and away on business a lot of the time. I hope he comes across as reasonably sympathetic.

As well as the obvious parallels though, I discovered other similarities while researching this piece that I didn’t expect to find. For example, in the Basile version, Cenerentola (1634), there is a magical date tree; Cenerentola nurtures this tree, placing it in a golden bucket, hoeing the earth around it with a golden hoe, and wiping its leaves with a silken napkin. She is rewarded for her efforts when it grows prodigiously, and a fairy appears – the fairy godmother figure. This is similar to the way in which a magical bird emerges from the hazel tree in the Grimm brothers’ Aschenputtel. In the second and third of my Lulu Baker books, Lulu grows some of the magical ingredients for her recipes in her own garden.

Cassandra, a kind of real-life fairy godmother, does not emerge from a plant, however; she is the one who supplies the ingredients, and the seeds for the ones that Lulu must grow. Lulu even has to fertilize one of them with her own tears (which she finds a considerable challenge, even with the help of onions). I based this element on the ancient Sumerian story of Inanna, but Aschenputtel also fertilizes her hazel tree with her tears.

It could also be argued that the Grimm brothers’ heroine is a bit more proactive than Perrault’s. Early on in the Aschenputtel story, we have the following scene:

It happened that the father was once going to the fair, and he asked his two step-daughters what he should bring back for them. ‘Beautiful dresses,’ said one, ‘pearls and jewels,’ said the second. ‘And you, Cinderella [Aschenputtel],’ said he, ‘what will you have?’ ‘Father, break off for me the first branch which knocks against your hat on your way home.’

This is interesting, because there are two possibilities as to why she has chosen this. The obvious reason is that she simply wants something to plant at her mother’s grave – which is what she does. This is where she weeps tears of grief onto the plant. So, yet another demonstration of her simple, virtuous nature: nothing more. Or is it? What if she knew that by tending the sapling lovingly, she would ultimately reap far greater rewards than the vulgar finery demanded by her greedy stepsisters? After all, she does go on to ask the tree outright for riches:

“Shiver and quiver, little tree,

Silver and gold throw down over me.”

Seems to me she had an inkling the hazel would have supernatural properties. Hey, good for her. She shows a bit more character than Perrault’s Cinderella, who would never presume to ask for anything – heaven forfend! Aschenputtel also asks help from the pigeons and the turtle doves in picking out the lentils her stepmother has thrown into the hearth. So I prefer to interpret her action as proactive, not only outwitting her stepsisters, but also demonstrating that slow, dedicated work might just be a better approach to life than stamping your foot and demanding things very loudly.

But there are probably as many differences as there are similarities between Cinderella and my Lulu Baker. For instance:

- Unlike Cinderella, Lulu isn’t perfect. She blunders into things, makes mistakes. And if she’s the victim of injustice, she sure as hell makes a noise about it! Meek she is not.

- Unlike Cinderella, Lulu is not beautiful. This is absolutely central to the story. Nor is she especially bothered about how she looks. She’s a bit lazy in that department, because her head is usually somewhere else. Cinderella, Snow White, Sleeping Beauty… the list of fairytale heroines whose physical beauty is a metaphor for their inner virtue – yawn – is endless. But where are the merely OK-looking ones? The ones whose best qualities lie in other areas – like being, say, fun to be around. A good laugh. Someone you might actually want as a friend. Hard to find, right?

- Unlike the Cinderella story, which is primarily about sibling rivalry, the main enemy in the Lulu stories is the stepmother figure. This is mostly because Lulu is younger than Cinderella: life is not yet about competing with contemporaries for romantic attention. True, she has a new stepbrother to contend with, but while he may be deeply unpleasant, he is not a direct competitor the way that Cinderella’s stepsisters are.

- Unlike the Cinderella story, it is the stepmother figure that gets her comeuppance – logical, since she is the main enemy. Even in the Grimm version, it is only the stepsisters that have their eyes pecked out; their mother escapes this fate. And after all, where marrying off daughters is a means of survival, or a dowry has to be provided, being a stepmother must be a most unenviable situation, laden with moral complexity. For most modern-day western stepmums, this is not the case. Varaminta, therefore, embodies all the characteristics of the stepsisters, as well as those of their mother.

All right, enough about ‘my’ Cinderella. Possibly you know of other modern Cinderellas – perhaps ones that are simpler tellings based on tradition that have altered the story according to the dominant philosophy of our time. Because let’s face it, Christanity, which provides the moral code for both Grimm and Perrault, arguably holds less sway today than it did then. Ye Xian’s story is influenced by religion of its time and place, as is the earliest known version of the Cinderella story, Rhodopis (Strabo, 1st century BC – though also mentioned by Herodotus five centuries earlier). I hate to say it, but perhaps what we have today is a sort of Christianity Lite. Or rather, Abrahamic-Religion-Lite. The Ten Commandments are good, they are right, but we’re not really bothered about taking the Lord’s name in vain, and can we please not have to stay in on the Sabbath as we’d rather go shopping. Also, loving our enemies is a bit hard. Thanks.

Depressing, isn’t it? But don’t get me started. Anyway I can’t assume the moral high ground here: if I adhered wholeheartedly to the Christian ideal, I would love and revere the character of Perrault’s Cinderella, and I don’t.

So: who would you pick as a Cinderella for our times, and why?

Picture credits:

Cinderella and her Godmother: silhouette by Arthur Rackham

Trying on the Shoe by Aubrey Beardsley

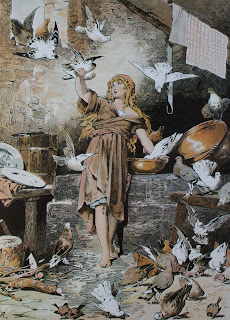

Aschenputtel by Alexander Zick (1845 - 1907) Wikimedia Commons

Cinderella: The Glass Slipper by Kay Nielsen