"There is a line

of Homer, which I forget, which tells of mules going up a mountain pass, and

you can hear the clatter of their hooves; and another tells of Apollo going

back in anger to Olympus, and his quiver against his armour booms as it goes.

And then there is Virgil’s line, though Latin can never quite equal Greek:

Quadrupedante putrum sonitu quatit ungula campum*

which tells of a horse galloping, without the aid of meaning, for the sound can be detected without knowing Latin. But these are are rare instances in which the magician has written his spell without mystery in plain earthly lettering; where the mortal ear can detect known words among the notes with which the spirit is called by the horns of elfland, and are not enough to enable us to decipher the other spells which give its power to metre. There must be rhythms in our hearts too deep for the eyes of scientists, rhythms which rhyme with these rhythms, all in harmony with some ancient order that may be called the technique of Creation.

"Well, I cannot explain it, but let us always remember that it is there; never let us read poetry as though it were prose, and let us never wrong a poet by reading one of his lines for instance like this:

Captain or col’nel or knight in arms.

"That is a jingle that ruins the stately form of a sonnet. It is not that you know how to pronounce the word colonel; that is a very trivial matter: the point at issue is whether Milton knew how to write a line of a sonnet. If he did, it must be obvious that he pronounced colonel as a three-syllable word, as it is written:

Captain or colonel or knight in arms

is a fine line opening a sonnet; it is like the beginning of a wide avenue leading up to a great house; the other is like a gap in a wire fence that rattles as you break through. Look again at the difference between the two lines ‘Captain or col’nel or knight in arms’ and ‘Captain or colonél or knight in arms’. You must not rob a poet of one of his syllables; it is like leaving out one of the black Cathayan letters from a magician’s spell; it is like pinching the horns of elfland and slightly narrowing them, so that they will not sing to you.

"Remember that this thing that I cannot explain is of the first importance, and that without it the music breaks down, even though you can read poetry in translation, which of course has the same effect on this particular magic that lead has on X-rays; but what happens is that our reason, which is not so near to Heaven as our emotions, is nevertheless able to see that much; it travels by its own power the paths of a wonderful country, but its hand is not held by a spirit leading it to fairyland.

"If then the metre is a spell whereby something is enchanted and brought in its transmuted form into sight of our mind’s eye, what then is the material which the spell transmutes or enchants? Well, one kind of material is somewhat similar to the base metals of the philosophers which they sought to change by means of alchemy; it is this world of ours, all the paths along which men walk and the fields lying about them. Indeed, roughly speaking, that was the principal material of all the poets up to the age of Stephenson. I do not mean the poet Stevenson, but that great inventor who, with James Watt, may have been whom Shahrazad prophetically had in mind when she told the story of the fisherman who released an evil spirit from a brass bottle, in which he had much better have stayed. These two men set rhythms going, and made certain changes in the British Isles that I need not go into, from which the poets began to turn away. It was only a tendency; they continued to write mainly about the world we know; but I think that strange remote poems like Khubla Khan and most of the country of Edgar Allan Poe and some of Shelley, like none of Wordsworth, are more frequent in the age of the steam-engine than they were before it. I think that in our own time there is a tendency to give Pegasus a rather longer gallop, to get away from the streets that have no longer the beauty of the country near Cork, which they say Spenser found good enough for the landscape of his Faery Queen.

"Of the Irish poets of our own time, the one who most habitually told of the fields around him was Francis Ledwidge. When he fled from this city, in which he had been apprenticed to a grocer, he did not flee like Coleridge in spirit to China, but in bodily form no further than a body can go on foot in a day, the thirty miles from here to Slane. And there he wrote one of his earliest poems, one verse of which goes like this:

Above me smokes the little town

With its white-washed walls and roofs of brown

And its octagon spire tones smoothly down,

As the holy minds within.

And wondrous impudently sweet,

Half of him passion, half conceit,

The blackbird calls adown the street

Like the piper of Hamelin.

"A.E. also wrote of Irish fields, but as though a spirit were constantly calling to him from India, and from times long past, and he seemed to see in the twilight, on hills familiar to all of us, figures of kings long dead, and shapes of gods remote from our Irish imagination. Yeats, it seemed to me, wrote of a stranger country; and, though he called it Ireland, it still remains strange to us; while James Stephens writes of things very near to our doors, things we might meet with in the streets of this city, but rather as though it were he that had come from far away to peer with bright eyes at our familiar things. Perhaps a leprechaun that had lost its way on a red bog far in the west and strayed to this city might write of our surroundings in some such way, sometimes deriding us for living here, where the horizon peeps so seldom over the end of a street, and sometimes resentful at being kept so far from the heather.

"And I cannot speak of Irish poets, writing of Ireland in our time, without quoting a poem by Mr. H.L. Doak, which has always seemed to me to be quite perfect. It was written during the last war [World War I] and was called ‘Johnny Durney’:

As into Dublin I rode down

With wonder I was filled,

The way they said in Blanchardstown

“Young Johnny Durney’s killed.”

Men leaned upon the spade to hear,

And women wiped their eyes,

And all because a lad grown dear

In a far country lies.

Great kings have made a bigger stir,

And yet have missed romance.

But here’s an Irish villager

Has got a grave in France.

Maybe a grand man fired the shot –

He laid a grander low.

Who’s Johnny Durney? Ask me not.

None but his own folk know.

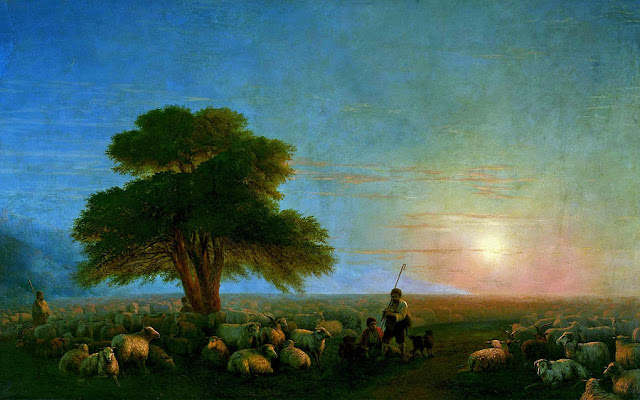

"One of the ingredients of poetry, then, is the world that we say we know, but that we do not always know very well until this enchantment of which I have spoken illuminates it, and our eyes see things clearly for the first time. The commonest things, things lying all round about us, and often to be seen from a nursery window, are for instance the usual material of Walter de la Mare; but he comes into the nursery like a witch, or a good fairy, always enchanting whatever he touches. This simple material, a flock of sheep, a dog and a shepherd, is shown in a poem that I will read to you – as also this enchantment.

Softly along a road of evening

Through a twilight dim with rose

Wrinkled with age and drenched with dew

Old Nod the shepherd goes.

His drowsy flock streams on before him,

Their fleeces charged with gold,

To where the sun’s last beam leans low

On Nod the shepherd’s fold.

The hedge is quick and green with briar,

From their sand the coneys creep;

And all the birds that fly in heaven

Flock singing home to sleep.

His lambs outnumber a noon’s roses,

Yet, when night’s shadows fall,

His blind old sheep-dog, Slumber-soon

Misses not one of all.

His are the quiet steeps of dreamland,

The waters of no-more-pain,

His ram’s bell rings ’neath an arch of stars,

‘Rest, rest, and rest again.’

[* 'The four-footed galloping horse-hooves shake the crumbling plain.' Virgil's Aeneid: tr: J. W. Mackail]

Picture credits:

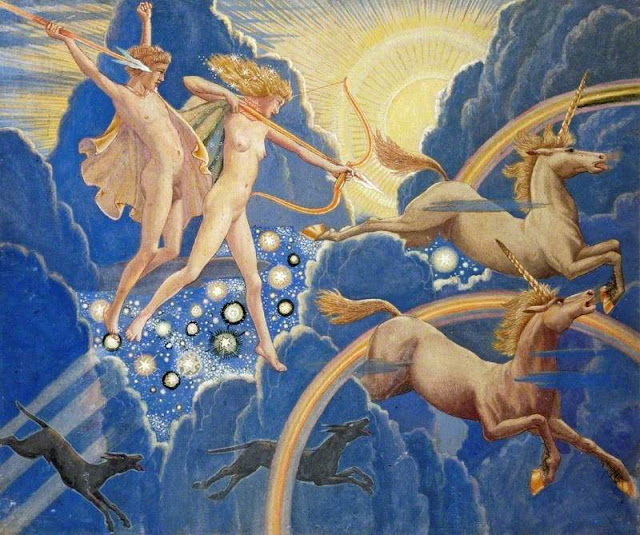

The Pleiades - by Bernard Sleigh (1872-1954)

The Horns of Elfland - by Bernard Sleigh (1872-1954)

Faun Whistling at a Blackbird - by Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901)

The Last General Absolution of the Munsters at Rue du Bois - by Fortunio Matania (c. 1915)

Shepherd with flock of sheep - by Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky (1817-1900)

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment