This wintry Russian fairy tale is my loose adaptation of ‘Morozko’ (‘Frost’), collected by Aleksandr Afanasiev and translated by W.R.S. Ralston in his book ‘Russian Folk Tales’ (Smith, Elder & Co, 1873).

There was once an old man who had three daughters. The wife had no love for the eldest of the three, her step-daughter Marfa. She made her get up ever so early in the morning, gave her all the work to do and never stopped scolding. The girl fed the cattle, fetched in wood and water, lit the stove, swept the floor and mended the clothes: she did her best, but her stepmother was never satisfied. ‘What a lazybones,’ she would grumble, ‘what a slut! Look, she’s left the brush out, and here’s some dust, and she’s left a speck here on the dishes!’

The old man was sorry for his eldest daughter but he didn’t help her. He was feeble and didn’t dare stand up to his wife. And the younger daughters were no better. They were always rude to Marfa, quarrelling and lying in bed till noon.

Well, the girls grew and grew until they were old enough to be married. The old man began thinking how he could get them settled, but his wife was wondering how to get rid of the eldest girl. One day she said to him,

‘Hey old man, let’s get Marfa married.’

‘Gladly!’ said he, creeping off to the warm sleeping place above the stove. But she called after him, ‘Get up early tomorrow, old man, harness the mare to the sledge and drive away with Marfa. And you, Marfa, get your things together in a basket and put on a clean shift: tomorrow you’re going on a visit.’

Marfa was delighted with this change in her fortunes. She slept well, and next morning she washed, prayed to God, packed her things and dressed in her best. Poor though that was, she looked such a pretty lass – a bride fit for any place whatsoever!

It was winter, and out of doors there was a rattling frost. In the hour before sunrise the old man harnessed the mare to the sledge and led it up to the door. Then he went inside. ‘Now then! Everything’s ready.’

‘Sit down and eat your breakfast,’ replied the old woman.

The old man sat, and made his daughter sit at his side. He took bread from the bread-basket, and broke it for himself and his daughter. Meanwhile the old woman served Marfa a dish of old cabbage soup and said,

‘There, my pretty pigeon, eat this and be off; I’ve put up with you for long enough. Drive Marfa to her bridegroom, old man! See here, old greybeard, this is what you do. You drive straight along the road until you come to the turning on the right that leads into the forest. Take her all the way up to the big pine that stands on the hill, and there hand her over to Morozko – to Father Frost.’

The old man opened his eyes wide, his mouth too. He stopped eating, and Marfa began to cry.

‘What have you got to squeal about?’ said her stepmother. ‘Your bridegroom is a beauty, and he’s rich! See how many things belong to him! Look at the firs, pines and birches, all dressed in snow-white ermine! He has resources anyone might envy, and he himself is a mighty lord.’

Silently the old man loaded the things on the sledge, wrapped his daughter in a cloak, and set off on the journey. After a while he reached the forest, turned off the road and drove across the frozen snow till they came to the middle of the forest. Here he stopped, made his daughter get out, laid her basket under the tall pine-tree and said, ‘Sit here and wait for the bridegroom. And mind you receive him as pleasantly as you can.’

Then he turned the horse around and drove off homewards.

Marfa sat and shivered. The cold had pierced her through. She would have cried for help, but no one would hear and she didn’t have the strength; only her teeth chattered. After a while, she heard something – a cracking and crackling among the fir boughs. Not far away, Frost was leaping from fir to fir, snapping his fingers. The sound came closer and closer. Presently he appeared on the very pine under which the girl was sitting, and from over her head he cried,

‘Art thou warm, maiden?’

‘Warm? Yes! I am warm, dear Father Frost,’ she answered.

Frost began to descend lower, all the time cracking and snapping his fingers. And he said to the girl,

‘Art thou warm, maiden? Art thou warm, fair one?’

Marfa could scarcely breathe in the freezing air, but she answered, ‘I am warm, Frost dear. I am warm, dear father!’

Frost began crackling more than ever; he snapped his fingers even more loudly, and he said to the girl,

‘Art thou warm, maiden? Art thou warm, pretty one? Art thou warm, my darling?’

By now Marfa was shuddering with cold. Through rattling teeth she whispered, ‘Yes, I am q-quite warm – d-dear Father Frost!’

Then Frost took pity on her. He wrapped her in warm furs, and robes embroidered with gold and silver threads, and he gave her a chest full of gold and jewels for her dowry. Dressed in this finery the girl was a real beauty. She sat on the chest in the snowy woods and sang for joy.

Next morning the old woman began baking the cakes for her step-daughter’s funeral. She told her husband to go and bring back the girl’s dead body: ‘Drive out, old greybeard, and wake the married couple up!’ As the old man harnessed the horse and drove off, the dog under the table began to bark:

‘Taff! Taff!

The master’s daughter in silver and gold

By the wedding guests will be carried along,

But the mistress’s daughters are wooed by none.

Taff! Taff!’

The old woman scolded the dog, but he kept on barking. Then she threw him a cake to shut him up, but nothing would stop him until the old man’s sledge drew up outside, the door flew open, and in came Marfa dressed in all her glory.

The old woman was thunderstruck. ‘Ah, you hussy!’ she cried. ‘But you won’t get the better of me. Husband, tomorrow morning you’ll take my daughters out to meet the bridegroom themselves. He’ll give them far better presents than he’s given her!’ So early next morning the two girls set out in the sledge, dressed in their finest, and the old man drove them into the forest and left them under the pine tree.

The girls sat there together, wrapped up well, but still they felt the cold.

‘This frost is skinning me alive!’ one grumbled. ‘I hope my bridegroom hurries up.’

‘Your bridegroom?’ said her sister. ‘Why shouldn’t he choose me? My bridegroom, you mean.’

‘You, why should he choose you? I’m far the prettier.’ And they began to argue and squabble, while the cold numbed their hands and stole under their wrappings, and their toes began to freeze. Soon, still a good way off, Frost began crackling and snapping his fingers and leaping from fir to fir. To the girls, it sounded as though someone was coming.

‘Listen! Here he comes at last, with bells on his sleigh!’

‘He may be coming, but he certainly won’t marry you. Look, your face is blue with cold.’

‘Your face is red, and peeling!’

And they both began blowing on their fingers.

Nearer and nearer came Frost, until he was rustling in the pine-tree right above them, and he called down,

‘Are you warm, maidens? Are you warm, pretty ones? Are you warm, my darlings?’

‘Oh,’ cried the girls, ‘it’s only old Frost. Of course we’re not warm! We’re chilled to the bone. We’re waiting here for our bridegroom, but the wretched fellow is late.’

Frost slid lower down the tree, cracking twigs and branches, snapping his fingers harder than ever.

‘Are you warm, maidens? Are you warm, pretty ones?’

‘In this terrible cold, are you joking? Our hands and feet are quite dead!’

Frost came even lower, and icy crystals showered around them. ‘Are you warm, maidens?’

‘We’re perishing, you old fool! Off to the bottomless pit with you!’ cried the girls – and froze to death.

Next morning, the old woman said to her husband, ‘Go harness the sledge and fetch my daughters. Make sure to take sheepskin wraps along, in case they’re cold. There’s a fierce frost outside.’ And as the old man drove away she began baking bridal cakes. But the dog under the table barked,

‘Taff! Taff!

The master’s daughter will be carried along

By the wedding guests with laughter and song;

But the mistress’s daughters will be carried back

As bunches of bones in an old brown sack.

Taff! Taff!’

It kept barking like that and couldn’t be silenced until the yard-gates opened and the old man drove in. Then the old woman ran out to greet her daughters and found them lying in the sledge, frozen as stiff as boards.

But Marfa married a neighbour’s son. They are now living happily together, and to show their respect for Father Frost, they make sure to leave out a bowl of sweet porridge for him, every Christmas Eve.

The 19th century translator adds:

To the Russian peasants, Moroz – Frost – is a living personage. On Christmas Eve it is customary for the oldest man in each family to take a spoonful of kissel, a sort of pudding; and then, having put his head out of the window, to cry:

‘Frost, Frost, come and eat kissel! Frost, Frost, do not kill our oats! Drive our flax and hemp deep into the ground.’

The Tcheremisses [people of Cheremushki, Eastern Siberia] have similar ideas, and are afraid of knocking the icicles off their houses, thinking that if they do, Frost will wax wroth and freeze them to death. In one of the Skazkas [wonder tales], a peasant finds his field of buckwheat all beaten down. His wife tells him, ‘It is Frost who has done this. Go and find him, and make him pay for the damage.’ So the peasant goes into the forest, and after wandering for some time, lights upon a path which leads him to a cottage made of ice, covered with snow and hung with icicles. He knocks at the door and out comes and old man – ‘all white’. This is Frost, who makes compensation by giving him with the magic cudgel and tablecloth which work wonders in so many tales.

Sometimes the Frost is described by the people as a mighty smith, who forges strong chains with which to bind the earth and the waters – as in the saying ‘The Old One has built a bridge without axe and without knife’: for the river is frozen over.

Picture credits:

Illustration to the fairytale Ded Moroz (Morosko) - by Elena Dmitryevna Polenova (1888)

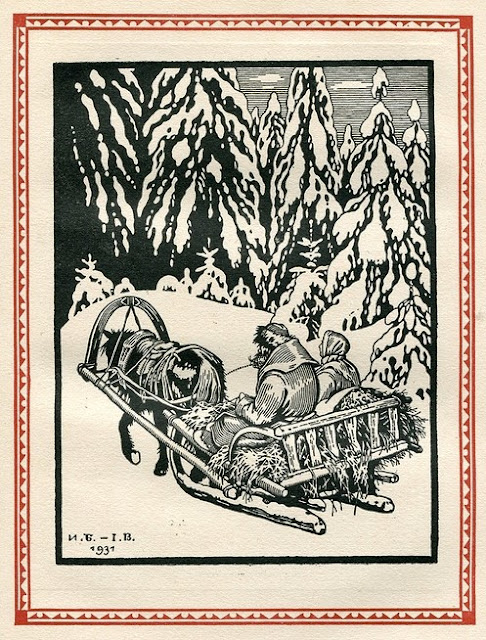

The old man drives Marfa into the forest - by Ivan Bilibin, 1931

Morozko (Father Frost) - by Ivan Bilibin, 1932

Marfa and Father Frost - by Arthur Dickson (1853 - 1959)

Illustration to the fairytale Ded Moroz (Morosko) - by Elena Dmitryevna Polenova (1888)

No comments:

Post a Comment